For many centuries, since medieval times, throughout the Renaissance and the Baroque period, during the nineteenth century and into our own day, Bohemian glass has been celebrated as one of Europe’s most treasured—and most distinctive—luxury products.

The idea of Bohemian glass summons different images for different people. For one, the name recalls stemware crafted from ruby-coloured enamelled glass cut with motifs drawn from the Central European forests, while for another Bohemian glass evokes images of huqqas painted with portraits of Persian princes or Ottoman beys. For many, the term Bohemian glass conjures the ethereal stained-glass windows of St Vitus’ Cathedral in Prague, illustrated above.

This blog will delve deep into the history of Bohemian glass, tracing its heritage from monastic production during medieval times through to the 21st century, in the process exploring the product’s many and varied guises.

This detail from a beautiful nineteenth century goblet, crafted from so-called overlay ruby glass, has been delicately cut with scenes and motifs drawn from the ancient Bohemian forests.

What and Where is Bohemia?

Bohemia is a historical country that now constitutes a large part of the Czech Republic. As a country and a region, Bohemia has a long and storied history.

Bohemia was a constitute kingdom in the Holy Roman Empire from the twelfth century, having previously enjoyed several centuries of political power. The region became a kingdom within the Habsburgs’ Austrian Empire in 1526, and in 1620, following religious turmoil, was demoted to a region within the Habsburgs’ expansive realm.

The region remained a core part of the Austrian Empire until the early twentieth century. When the latter was dissolved following the resolution of the First World War, Bohemia became the westernmost province of the newly founded Republic of Czechoslovakia. After a troubled twentieth Century, in 1993 Czechoslovakia dissolved into the current countries of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, with Bohemia constituting much of the former’s central and western portions.

This map shows the location of the historical Kingdom of Bohemia relative to the cities of Berlin, Vienna, and Kraków.

Geography and Glassmaking in Bohemia

The geography of Bohemia is perfectly suited to glassmaking, the region’s natural characteristics being conducive to the production of a very high-quality product. Chalk and potash proliferate, and when the two are combined and utilised during the glassmaking process, the result is a tough, brilliantly clear, colourless glass. Silica, the substance from which glass is made, is abundant in Bohemia, providing plenty of raw material for the manufacturing of glass goods.

Glass produced with chalk and potash is more stable than other European products, particularly Italian counterparts—glass from Murano traditionally being Bohemian glass’ primary competitor. Bohemia’s unique glass allows for more elaborate structural forms and more intricate surface decoration. In addition to chalk and potash, Bohemia is situated within the heart of Central Europe’s vast forest, which provides plenty of material to fire the kilns so crucial to the manufacturing process.

This nineteenth century huqqa, crafted from parcel gilt overlay glass, was produced for the Persian market, as demonstrated by the inclusion of portraits of two Qajari kings, namely Naser al-Din Shah and Mozaffar al-Din Shah.

The Long Tradition of Bohemian Glassmaking (c. 1200 to 1500)

Bohemia has a long and celebrated tradition of glassmaking. While there are indications of glass production occurring during classical and early medieval times, glassmaking became a substantial industry during the thirteenth century. At this time, glassmaking was pioneered by Benedictine monks in the Lusatian Mountains, who manufactured coloured glass for use in local and regional monastery and church stained-glass windows.

Under Charles IV, the Holy Roman Emperor for much of the middle of the fourteenth century, window glass production proliferated: local glass was used in Prague Castle and Saint Vitus’ Cathedral, for instance. Charles invited Venetian glassmakers—then the undisputed masters of the craft—from Murano to Prague in order to modernise Bohemia’s burgeoning industry.

During Charles IV’s reign, native Bohemian glassworkers produced great quantities of so-called ‘forest glass’, which features a green hue due to natural impurities and a bubbled internal structure. A local market existed for pieces made in this manner, and once Bohemian glass became internationally renowned later producers reinterpreted this earlier product, utilising its distinctive look to create a Bohemian style.

The first commercial glassworks were established during Charles IV’s reign, and the first true glass factory—for producing windows and other glass products in greater quanity—was founded in Chřibská in 1414. During the following decades, the glassmaking industry would blossom in Bohemia: by the early sixteenth century, there were at least 34 commercial factories present in the region. This exceptional growth allowed Bohemian glass to dominate the European market during the Renaissance.

Bohemian Glass During the Renaissance and High Baroque (1500 to 1750)

During the Renaissance and the High Baroque—from sixteenth century until about 1750—Bohemian glassworkers were the dominant producers of decorative glassware in Europe, creating a distinctive product that was sought after by kings and queens from all corners of the continent.

The catalyst behind the Bohemian glassmaking explosion was Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, who in 1588 invited an Italian gem cutter to establish the first gem cutting workshop in Prague. Once successfully established, a Bohemian artisan called Caspar Lehmann became court gem cutter to the Emperor.

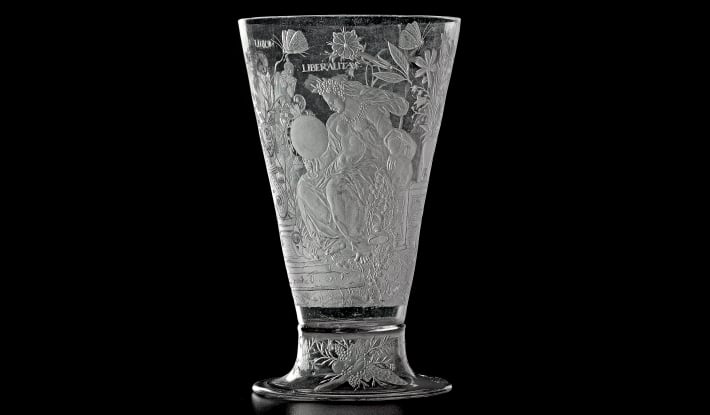

Dating to 1605, this goblet is by Caspar Lehmann, the leading artisan of his day and the pioneer of glass engraving, whereby the tools and techniques of gem engraving are adapted to this new medium.

Lehmann is of paramount importance to the history of Bohemian glass as he was the first person since the ancients to adapt the tools and techniques of gem cutting to glass. Lehmann utilised bronze and copper wheels to engrave glass, producing intaglio (or deep cut) and high relief engraving. Bohemian glass, with its unmatched stability, was perfectly suited for this purpose.

Furthermore, Lehmann perfected the production of overlay glass—that is, glass of one colour laid atop glass of another and fused together during the production process. With overlay glass, the upper layer can be removed by engraving, thereby revealing the differently coloured layer below.

With Lehmann’s innovation, Bohemian glass became widely known, principally because it was the only glass to be cut and engraved in this way. Over the decades of the seventeenth century, the region’s products grew in repute, and by 1700 Bohemia was the world leader in terms of glass production. It was at this time that the term ‘crystal’ was applied to Bohemian products to distinguish them from other European counterparts; crystal was an appropriate adjective, because the qualities of the pure, clear Bohemian glass naturally resembled quartz stone.

Bohemian glassware became as prestigious a luxury commodity as fine jewellery, and the finest examples were collected by European royalty. Spectacular chandeliers crafted from Bohemian glass were to be found in the palaces of Louis XV of France, Elizabeth of Russia, and Maria Theresa of Austria.

The Hall of Mirrors at Versaille features 43 Bohemian glass chandeliers installed late in the eighteenth century during the reign of Louis XV.

The Nineteenth Century and Beyond (1850 to 1950)

With the end of the late Baroque and the birth of Neoclassicism, taste for Bohemian glass products in Europe waned. The vibrant colours and intricate detailing of the Bohemian style found little favour throughout a continent that had grown to admire the restrained elegance of the Neoclassical.

During the latter half of the nineteenth century, however, Bohemian glassmakers enjoyed a renaissance. With an ever-more connected world, producers looked to new processes and technologies that allowed for production on a greater scale, thereby satisfying growing demand among middle-class consumers.

Ornate vases crafted from coloured opaque glass and enamelled with cursorily painted floral subjects were exported throughout the globe; glass products adorned with coloured lithographic prints of renowned paintings proved popular, too. The mainstay of decoration, however, remained engraving, and engraved glass, richly coloured and cut with abstract motifs and designs inspired by the Bohemian landscape, continued to be popular among refined collectors.

Producers did not limit themselves to vases and other purely ornamental pieces, however. As consumers began to demand high-quality items for daily purposes, and producers were capable of sustaining demand thanks to new production techniques, so makers turned their attention to tableware, stemware, and other household items, all crafted with the skill and care that earned Bohemian producers their great prestige.

Bohemian Glass and the Persian and Ottoman Markets

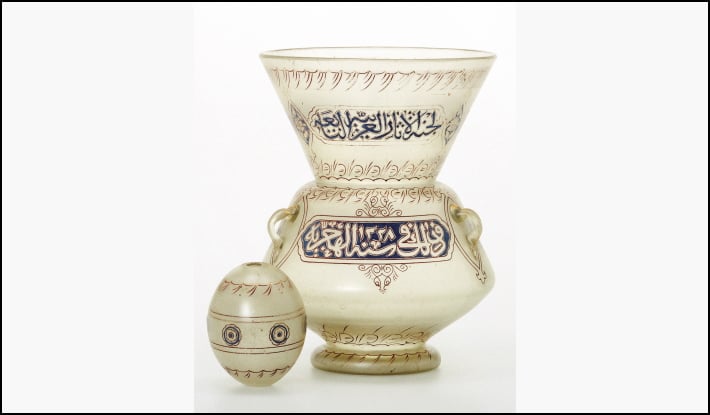

Perhaps the most intriguing development in Bohemian glass production during the nineteenth century is the establishment of a large and flourishing export market in the east. Vast numbers of enamelled glass huqqa pipes, decanters, rosewater ewers, and mosque lamps, enamelled and engraved with portraits of important figures from the Persian Qajar dynasty or dignitaries from the Ottoman Empire, made their way to Persia and Iran.

Bohemia was an immensely important centre for the production of Islamic art, and pieces by Bohemian producers found their way into mosques from Cairo to Tehran.

This delicate enamelled glass mosque lamp was created around 1910 in Bohemia for a patron in Cairo (Image courtesy of The Khalili Collections, London).

Bohemian Glass and the Art Nouveau

By the turn of the twentieth century, Bohemian artisans became leading producers of pieces in the Art Nouveau, or Jugendstil, utilising previously perfected techniques—such as enamelling and engraving—in the creation of pieces adorned with natural forms. By the 1920s, the same producers became pioneers of the Art Deco style.

This capacity to change and adapt to circumstances demonstrates the versatility—and ingenuity—of Bohemian producers. During this period, several celebrated producers became household names, including Lobmeyr, Moser, Loetz, and Kralik. Moreover, the success of Bohemian producers inspired others in the region, providing the impetus for the foundations of firms such as Swarovski in Austria.

Moser, the maker of this beautiful Art Nouveau period piece, has been one of the leading producers of Bohemian glass since its foundation in the mid nineteenth century.

The Legacy of Bohemian Glass and Crystal

From manufacturers of stained-glass windows during the late medieval period, to innovators of glass engraving during the Renaissance, to leading producers of luxury high Baroque glassware, to pioneers of the Art Nouveau, Bohemian makers have been at the forefront of European glassmaking for the best part of a millennium.

During the twentieth century, when Bohemia was a core region of Czechoslovakia, production of high quality glass pieces continued, the techniques and styles employed during this period often recalling early moments from the region’s long history of manufacturing. Today, production continues as ever, though glassware produced in the historical region of Bohemia is often known simply as Czech crystal.

The pieces produced by Bohemian glassmakers, whether engraved glass vases, cut glass stemware, or enamelled glass huqqas, continue to be especially collected and collectable—as objects of art, and also as beautiful pieces that can be used and enjoyed.

For further reading on the history of glassware, please refer to our previous blog: Antique Glass: A History of Techniques and Styles