Following the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, revelers rushed to entertainment venues across America to raise a glass of cheer! Americans, still in the throes of the Great Depression, gladly took the opportunity to splurge for a night on the town or an afternoon at the theater to relieve their worries. Art Deco and Streamline Moderne design adorned the buildings, captivating customers and renewing their spirits. Vintage postcards from the era transport us to a world of high style, glamour, progress, and optimism.

Popularized at the 1925 Paris Exposition des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes, the Art Deco style reached its pinnacle at America’s world’s fairs and expositions in 1939-1940. The term “Art Deco” refers to a set of design characteristics including rectilinear and geometric modes, stepped forms, stylized flowers and motifs, ziggurats, sunbursts and chevrons. Streamline and geometric features were frequently enhanced by exotic and opulent applications.

The style was applied to decorative objects, buildings, sculpture, costumes, interior design, paintings and murals. Driven by the latest in technology, designers interpreted a streamlined version of Art Deco featuring sleek lines, glass, neon lights, chrome trim and smooth surfaces.

In the late 1920s, and throughout the 1930s, America saw a boom in construction creating fine examples of Art Deco and Streamline Moderne architecture. Some projects were fueled by captains of industry interested in expanding their wealth or contributing to the betterment of society. But many projects were the result of municipal grants and public works programs put in place to relieve the hardships of the Great Depression. The construction of entertainment venues flourished during this period and many still exist today.

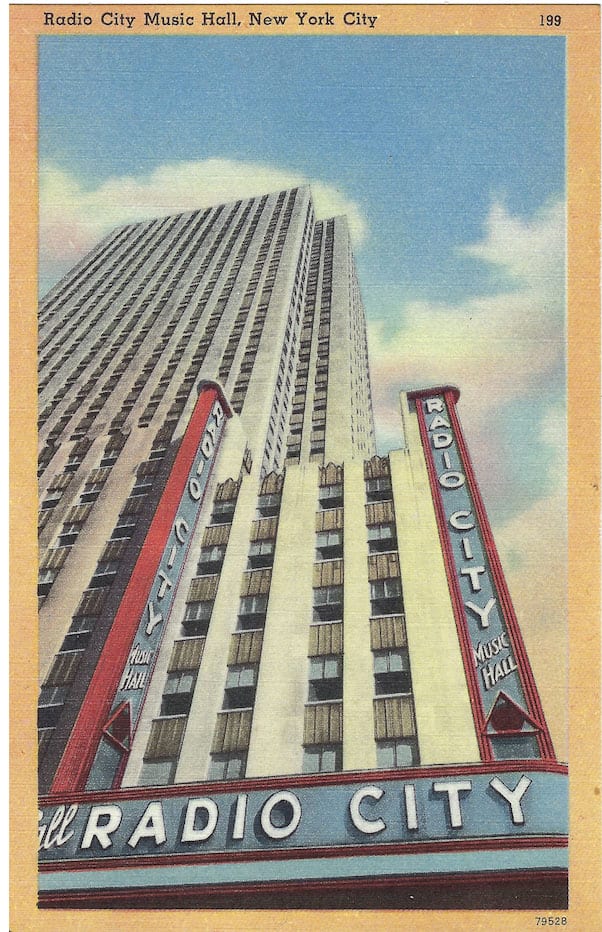

Nicknamed the Showplace of the Nation, Radio City Music Hall in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, is the headquarters for the Rockettes, the precision dance company.

Image courtesy Anne Peck-Davis and Diane Lapis

Radio City Music Hall

In 1928, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. entered into an agreement to build a new Metropolitan opera House in midtown Manhattan. When the opera house plans fell through, the concept for Rockefeller Center was born. The huge complex would headquarter the Radio Corporation of America and include Radio City Music Hall, a grand 5,960-seat Art Deco theater.

Architect Edward Durell Stone and industrial designer Donald Deskey were selected to design creative aspects of the Music Hall with theatrical entrepreneur Samuel “Roxy” Rothafel as an advisor. The gorgeous Art Deco theater opened on Dec 27, 1932, with a star-studded variety show including a precision dance team, later known as the Rockettes.

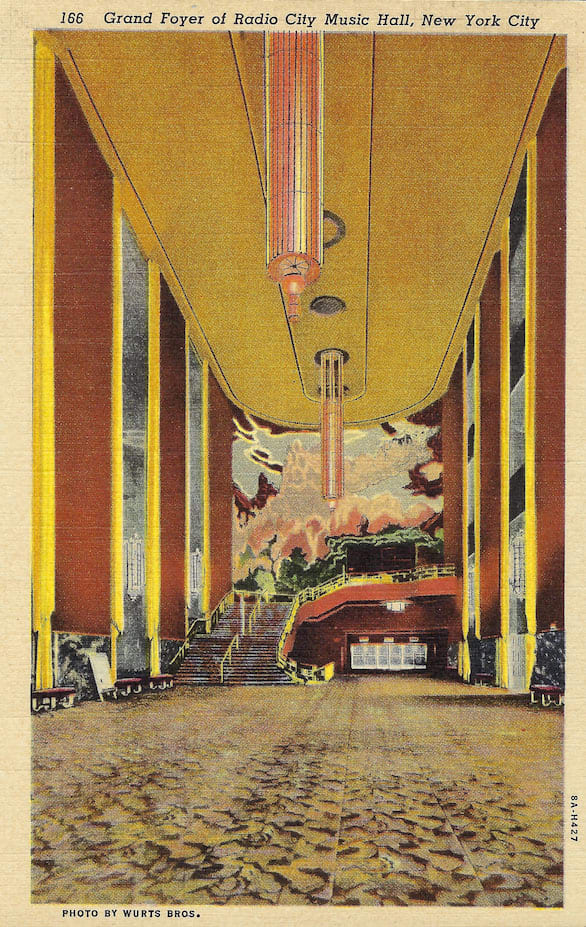

The elliptical-shaped Grand Foyer of the Radio City Music Hall.

Image courtesy Anne Peck-Davis and Diane Lapis

Attendees pouring into the elliptical-shaped Grand Foyer were treated to “The Quest for the Fountain of Eternal Youth,” a vast mural created by Ezra Winter. Overhead two massive cylindrical-shaped chandeliers set the tone of grandeur before entering the performance. The impressive theater’s auditorium features an immense golden proscenium arch emulating a sunrise, a popular Art Deco motif. After the show, a trip to one of the men’s or ladies’ lounges reveals themed murals by respected artists of the day. The two largest of these retreats, located in the lower level’s Grand Lounge, invite you to relax in an atmosphere of enchantment or enjoy refreshment from the bar. Here you will find the ethereal, History of Cosmetics, created by Witold Gordon in the ladies’ powder room and Stuart Davis’ abstract, Men Without Women, in the men’s lounge. Deskey unified the theater by designing custom furniture and lighting, coordinating the installation of geometric carpets and wall coverings, solidifying the luxurious Art Deco look.

Outside the Music Hall three signs, 90 feet tall, are emblazoned with the hall’s name and a stunning streamlined marquee is highlighted with neon lights accentuating its curvature. The building’s façade, clad in Indiana limestone, features three vibrantly colored metal plaques depicting theatrical themes designed by Hildreth Meiere. Saved from the wrecking ball and achieving landmark status in 1978, Radio City Music Hall and the iconic Rockettes are still enjoyed today.

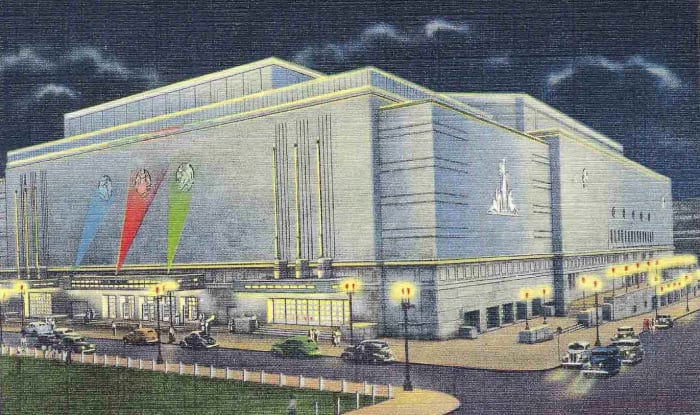

The Municipal Auditorium, Kansas City, was a glimmering idea inspired by the darkness of The Depression.

Image courtesy of Ann Peck-Davis and Diane Lapis

Municipal Auditorium, Kansas City, Missouri

The Municipal Auditorium was funded by a ten-year bond plan aimed at providing work and drawing tourists to Kansas City during the Great Depression. Championed by the Civic Improvement Committee, the bond passed in 1931 with support from local political boss Thomas Pendergast. Heavily inspired by Radio City Music Hall, the Auditorium was designed by Gentry, Voskamp and Neville in collaboration with the architectural firm Holt, Price and Barnes. The Municipal Auditorium, featuring Art Deco and Streamline Moderne details, was completed in 1935 and highly acclaimed in both the Architectural Record and the Princeton Architectural Press. Designed for multifunction entertainment, the ten-story structure encompasses an entire city block including an Arena, Music Hall, Little Theater and Exhibition Halls.

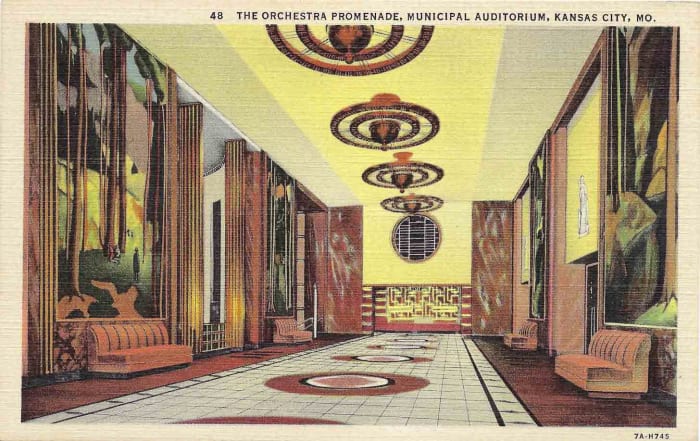

Design of the Municipal Auditorium, Kansas City, was influenced by Radio City Music Hall.

Image courtesy Anne Peck-Davis and Diane Lapis

What sets this space apart from other venues are the lavish materials, lighting, metalwork and artwork embellishing the Auditorium. Walter Alexander Baily created four massive murals for the Orchestra Promenade entitled Four Seasons, representing the different stages of life. The grand staircase off the Grand Foyer gives access to the Orchestra Promenade and features a 27-foot-high mural painted by Ross Brought, Mnemosyne and the Muses. The grand staircase is clad in gray and golden Sienna marble with streamlined metalwork railings designed by Homer Neville. Numerous entertainment options offered at the Auditorium include, musical performances, plays, speakers, beauty pageants, and sporting events. The Arena hosted its first basketball game in 1936 (Stanford defeated Central Missouri) and has continuously featured NCAA games over the years. Thoughtfully, the architects constructed an underground tunnel connecting the Auditorium to the nearby Muehlebach Hotel. Here patrons could enjoy dining, dancing, and drinking after an event. The Municipal Auditorium, a jewel of an attraction in the Midwest, combines Art Deco beauty with function to create a memorable experience.

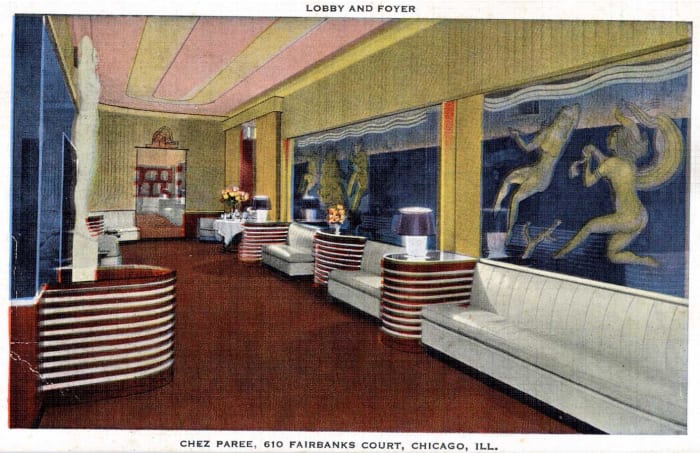

A modernist design was used throughout the Chez Paree Theater Restaurant in Chicago, unifying various elements from the Art Deco period.

Image courtesy Anne Peck-Davis and Diane Lapis

Chez Paree Theater Restaurant

Hollywood glamour and Art Deco design reigned supreme at the Chez Paree Theater Restaurant in Chicago. Its long arc of providing top-notch entertainment from 1932 to 1960 featured singers, comedians, vaudevillians and the famous opening act of long-legged showgirls in skimpy outfits called the Adorables. A modernist design was used throughout the “Shay” unifying various elements from the Art Deco period. The lobby, theater, bar, Key Club Room and lounges were smartly furnished with curved tables and chairs accented with bold stripes, geometric lamps and chrome accents.

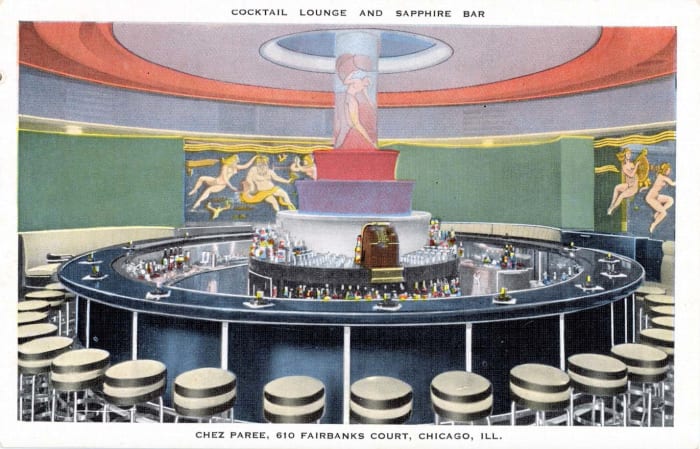

You could literally buy a round at the circular bar of the Chez Paree Cocktail Lounge and Sapphire Bar.

Image courtesy Anne Peck-Davis and Diane Lapis

The decorative style featured undulating lines above mythological and space age-themed wall murals with ever-changing bright colors from neon lights. The patrons at the Chez Paree packed the house when radio, film and stage legends such Sammy Davis, Jr., Ethel Merman, Sophie Tucker and Nat King Cole appeared. Enjoying steakhouse fare, restaurant goers could enjoy 75-cent cocktails, including one named the ‘Chez Paree.’ Visitors to the 1933-1934 Chicago World’s Fair made the Chez Paree a popular nighttime destination.

The wonderful Earl Carroll Theater on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, 1938.

Image courtesy Anne Peck-Davis and Diane Lapis

The Earl Carroll Theater

Earl Carroll, a consummate theatrical producer and director, built the Earl Carroll Theater on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood in 1938. At the time, it was the largest entertainment hall in the world. Combining the best features of a nightclub, restaurant and theater, the Earl Carroll incorporated Streamline Moderne elements throughout the interior and exterior of the complex. The renowned architect Gordon Kaufmann emphasized sleekness and modernity by means of smooth surfaces, curving forms, and horizontal lines.

On the front of the building, a 20-foot tall neon image of Carroll’s leading lady and romantic partner, Beryl Wallace, greeted patrons as they pulled up to the entrance. The building’s white reinforced-concrete exterior was asymmetrically offset by a three-bay porte-cochère, allowing patrons to be dropped off safely from the elements. Two bands of steel-encased windows emphasized the horizontal element. Semi-circular planters softened the hard-edged lines of the structure. Upon entering the foyer, theater goers encountered a 15-foot aluminum-covered plaster statue named the Goddess of Neon. Etched glass walls of mirror, a revolving tear-drop-shaped stage flanked by black structural glass, a majestic staircase, fluted columns made of glass, and pastel-hued neon tubing exemplified the architect’s interpretation of the Streamline Moderne style. The building still exists and is currently undergoing restoration, waiting for the next generation of nighttime revelers.

The Will Rogers Memorial Auditorium achieved landmark status in 2016 and remains a vibrant part of Fort Worth’s culture.

Image courtesy Anne Peck-Davis and Dianne Lapis

Will Rogers Memorial Auditorium

The Will Rogers Memorial Auditorium was named for the beloved entertainer, political humorist, radio personality, news columnist, and actor known for his tagline, “I never met a man I didn’t like.” Rogers was born on a ranch in Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, to parents of Cherokee descent. His first break in show business was an act featuring a lariat and a pony cementing his persona as an all-American cowboy.

Completed in 1936, just one year after Will Rogers’ death, the auditorium was funded by the Works Progress Administration and constructed in Fort Worth, as part of the Texas Centennial Celebration. The complex was designed with an auditorium, coliseum for rodeo and horse shows, and a 208-foot high Pioneer Tower, brightly lit and visible for miles.

The architectural firms of Wyatt C. Hedrick and Elmer G. Withers were responsible for design of the project. Noteworthy, the buildings are influenced by regional culture and streamline architecture creating a theme that interprets Art Deco Texas-style. Elements of western motifs are evident in the stylized plaques, carvings, and friezes that decorate the interior and exterior of the complex. Herman Koeppe is credited for the sculpted bronco rider appearing on the façade of the Coliseum and the tiled frieze adorning both the Coliseum and Auditorium. The colorful frieze bands at the top of each building depict Fort Worth’s history from Native American inhabitants, to Cowtown, and finally modern city. A life-size bronze statue of Will Rogers and his horse Soapsuds is located outside of Pioneer Tower.

The Pioneer Palace, a popular eatery, was located in the Rogers complex from 1936 to 1966. Originally serving as a restaurant and saloon for the Centennial, the concept for this old-time dance hall with vaudeville acts was conceived by the theater impresario Billy Rose. Over the years, patrons could enjoy a sandwich and a beer while being entertained by pied-piper jugglers, fire-eaters, tap dancers, and striptease artists. One reporter noted, “the Palace was an expansive, gaudy, noisy… rough-and-tumble place that winked at almost anything so long as everybody was having a good time – a laughing, buxom country wench, with pigtails flying.” One section of the original 40-foot long bar is currently installed at the Backstage Club inside the tower at the Coliseum.

The Will Rogers Memorial Auditorium achieved landmark status in 2016 and remains a vibrant part of Fort Worth’s culture. For over 70 years the Coliseum hosted the legendary Fort Worth Stock Show and Rodeo and now features equestrian events and exhibitions. Musical performances are held in the Auditorium including concerts by the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra. Although the Pioneer Tower remained dark for decades, after undergoing an extensive renovation, it now shines forth in all its glory.

You May Also Like

Lounge Lovelies Mixed Booze With Sex Appeal

Meet Leonard Lauder: Billionaire Businessman, Philanthropist, Postcard Collector