Considered to be the only American to work in the true couture tradition, Charles James, one of the most influential fashion designers of the 20th century, thought of himself as more of a sculptor of dress than a dressmaker. He manipulated fabrics into dramatic shapes using complex seaming and sometimes complicated understructures to create his singular vision of timeless elegance.

Charles James, 1952.

Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Photograph by Michael A. Vaccaro / LOOK Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

James’ ball gowns, for which he is best known, weren’t called wearable sculptures for nothing. Some of his gala creations weigh 10 to 20 pounds. Women who wore them, however, claimed they felt weightless, as James engineered them to distribute the weight for ease of movement. He would measure the depth of a torso, rather than simply its length and width, and his designs were made so that they would be perfectly poised on the hips and flow beautifully.

Born in England, James moved to Chicago when he was 18 and started out as a milliner in 1926, later opening his dressmaking business in New York. His career began to pick up in the 1930s and peaked between the late 1940s and mid-1950s, when he and his scarce and highly original gowns developed a cult following among society’s most prominent women, including Austine Hearst, wife of the publishing scion William Randolph Hearst Jr.; Millicent Rogers, granddaughter of the Standard Oil tycoon Henry Huttleston Rogers; New York socialite Babe Paley; and actress Marlene Dietrich.

Socialite Babe Paley wearing a crimson James’ ball gown, 1950.

Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Photograph by John Rawlings, Rawlings / Vogue / Condé Nast Archive. Copyright © Condé Nast

Charles James’ silk and cotton evening gown, 1949-1950.

Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Arturo and Paul Peralta-Ramos, 1954

Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Arturo and Paul Peralta-Ramos, 1954

James produced some of the most memorable garments ever made during his career. A master of understanding the dynamics between texture, form and color, he would often combine different fabrics in like colors with different light-reflective qualities or several different like fabrics in different colors to heighten the drama of his evening wear.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which has many of James’ designs in its collection, he worked for years on refining certain constructs, shapes and seam lines that particularly expressed his vision of artistry through engineering. Many of his pieces are conceived asymmetrically and possess a sense of movement and vitality that is a signature characteristic of his work. Also prevalent throughout his work are many historical references in shapes and construction, especially the drapery forms of the 1870s and early teens.

A famous Cecil Beaton photograph from 1948 of nine models, including Marilyn Ambrose, Dorry Adkins, Carmen Dell’Orefice, Andrea Johnson, Lily Carlson, and Dorian Leigh, wearing various gowns by Charles James while posing in French & Company’s eighteenth century French paneled room.

Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, photograph by Cecil Beaton, Beaton / Vogue / Condé Nast Archive. © Condé Nast

The brilliant designer was not without flaws, however. He was famous for his mercurial temperament, being a perfectionist, and had a reputation for being a fiscally irresponsible businessman. It was said that if a customer ordered a James’ creation for a special event, she was advised to have a backup outfit, as he would not always deliver in a timely manner. Although extraordinarily successful as a designer, his label was never financially successful and solely relied on the patronage of society women and heiresses.

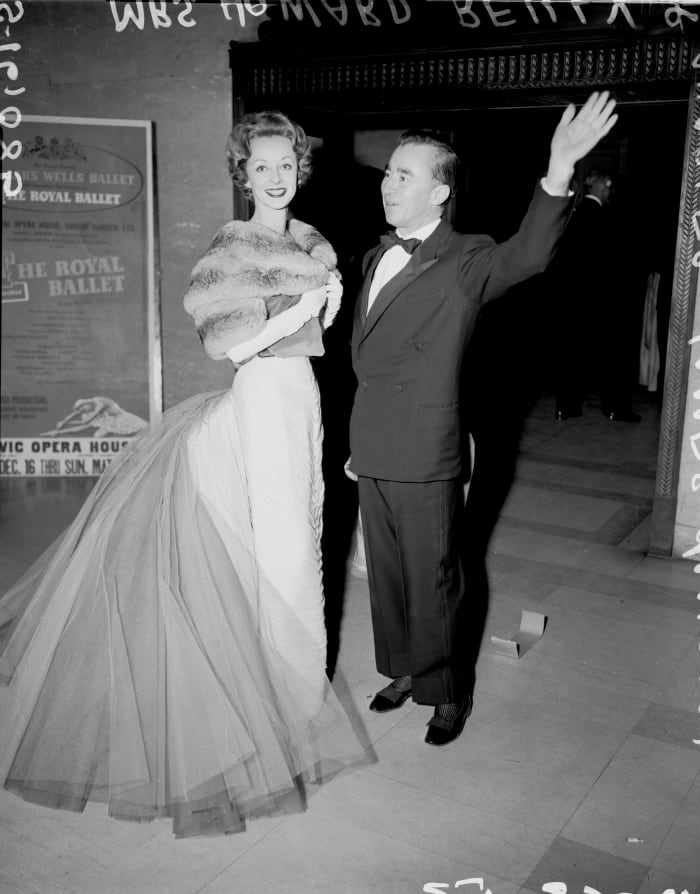

Fashion designer Charles James with one his clients, Mrs Howard Reilly, wearing one of his Butterfly gowns in 1957.

Courtesy of Chicago History Museum/Getty Images

Using clever boning, padding, crinolines and bustles, the understructures of James’ creations recalled those of the previous century. As the proverbial saying goes, a woman should wear the dress and not the other way around; this was not a concern of James, however. The Met Museum said that many of his evening gowns disregarded the body entirely, and the wearer would instead assume an otherworldly, inhuman figure.

These ball gowns are just some of his creations that beautifully show off his architectural skills and highly structured aesthetic:

Ball Gown, 1950-52

Silk ball gown, 1950-1952. This belonged to Marietta Tree, a client Charles James named his Tree ball gown after.

Courtesy the Met Museum

According to the Met Museum, the design of this ball gown incorporates a detail seen in late nineteenth-century dresses: The torso seems to emerge out of the folds of the skirt. In his rendering of the historicist effect, James generated a sophisticated technical solution to conform to his preference for continuous pieces of fabric that are draped, tucked, and darted to fit. The fabric is shaped and fitted over the hips of the torso to become the draped apron.

Petal Gown, 1951

The Petal ball gown, a variant on a dress first made for Millicent Rogers in 1949, appeared in Vogue in 1951, when it was photographed by renowned German fashion photographer Horst P. Horst and included in James’ Black and White collection. James described that version of the dress as a “curving stem of black velvet above petals of black satin, above 25 yards of blowing, billowing white taffeta.” He revived the design in 1958, as a ready-to-wear dress for the junior market.

According to the Chicago History Museum, which has the black-bodiced version from 1951 in its collection, “If James were not so clever, the Petal’s twenty-five yards of material would have created an undesirable bulk at the waist. He solved this by stitching most of the material to petal-shaped hip panels and only one layer to the waist seam.”

The museum noted that the skirt’s tremendous weight caused extensive damage to its interior construction and it took nearly 120 hours of conservation work to stabilize the gown for display.

The Petal gown in black velvet and silk, designed in 1951. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum

Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum

Lifelong Chicagoan Mrs. Byron S. Harvey Jr. (née Kathleen Whitcomb), who regularly appeared on the city’s best dressed list, donated three James’ garments to the museum, including the Petal gown, but photographs suggest she owned at least five. Mrs. Harvey was both a client of James’ and his friend, and hosted a wedding reception for him and his wife, Nancy, in July 1954. The following October, she wore her Petal gown to the Consular Ball at Chicago’s Conrad Hilton Hotel.

Four-Leaf Clover Gown, 1953

This Clover Leaf dress is in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. The Metropolitan Museum of Art also has a couple of versions in its collection.

Courtesy of the V&A Museum

Said to be James’ favorite dress, this sculpted creation made of the costliest silks – white duchess satin, black velours de Lyon, and ivory silk faille – spans out like a four-leaf clover. Constructed from 30 pattern pieces and built on an infrastructure of mesh, boning, cotton and horsehair, it weighs in at an extravagant 10 pounds, with most of its heft at the hips.

While his inspiration for this dress was likely the 1860s silhouette supported by a cage crinoline, its construction is far more complex than its precursor made of concentric steel wires connected by linen tapes. This one was built using two separate understructures of boning and stiff interfacings to give it shape and balance. The skirt was engineered to rest comfortably on the hips, and, unlike the cage crinoline, to effectuate a graceful glide rather than a back and forth sway.

Another version of the Clover-Leaf gown in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Josephine Abercrombie, 1953

Back view.

Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Josephine Abercrombie, 1953

James designed this gown for Austine Hearst, wife of William Randolph Hearst, and a fashion columnist and best-dressed lister, who described the designer as “a complex genius.” She was supposed to wear it to the Eisenhower Inaugural Ball in January 1953, but it was not completed in time, so she wore it to a ball in June.

According to the Victoria and Albert Museum, in a letter from 1971, James said of the gown: “This design represents the ‘bringing’ together of many parts from which a whole series of designs had been made … It seemed to me to be somewhat of a thesis and as such has been programmed as the last design I intend to make.”

The Clover Leaf gown has become one of the icons of mid-century couture, the ultimate in glamorous, show-stopping evening wear, and, by James’ own evaluation, his pinnacle in dressmaking.

Swan Gown, 1954

Charles James’ Swan gown, 1954, brown silk chiffon, cream silk satin, with a layered understructure of yellow, purple, light brown, and brown nylon tulle.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum 2009

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum 2009

Among James’ many allusions to historical silhouettes and decoration, his Swan gown is the most literal. Borrowing from the Victorians, he interpreted the 1870s bustle dress in construction, form, and decoration to render the silhouette of a swan folding its wings.

The skirt is composed of six layers, made up of 1,080 square feet of tulle, combined in various colors to give it depth and luminosity. The gown weighs in at 12 pounds, despite its ethereal appearance. The beautiful curvature of the bodice back is signature James’ anatomical styling designed to displace extra flesh that might ruin the graceful line.

The yellow, purple, light brown, and brown nylon tulle layered underneath the gown.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum 2009

Nancy James wearing her husband’s Swan gown.

Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Photograph by Cecil Beaton, The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s

The gown is immortalized in a Cecil Beaton photograph of James’ wife, Nancy, posing by light-filled Pellon-covered windows in the James showroom.

Butterfly Gown, 1955

Charles James’ Butterfly gown, 1955, silk chiffon, silk faille, DuPont nylon tulle.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. John de Menil, 1957

Using silk chiffon, silk satin and twenty-five yards of nylon tulle, James sculpted this Butterfly gown that sensually wrapped around the wearer and made the woman who wriggled into its narrow cocoon-like body feel all the enchantment of a shimmering winged beauty.

Although weighing a whopping 18 pounds, James’ innovative construction made it feel weightless to the wearer, and the enormous tulle bustle, representative of a butterfly’s wings, moved swiftly with the body.

The Butterfly side view.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. John de Menil, 1957

All of the different colored tulle layered underneath the gown.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. John de Menil, 1957

Taking inspiration from the tightly fitted bustle dresses of the early 1880s, the Metropolitan Museum of Art said James exaggerated the torso length of the sheath with “the highest bustline in 125 years” and layered transparent tulle in unexpected colors to accrue depth of tone and iridescent shimmer to the surrogate wings.

Only five examples of the Butterfly ball gown are known to exist, including one in the collection of the Met Museum and one in the collection of the Chicago History Museum.

Only five examples of the Butterfly are known to exist. This version in a different color scheme was made in 1954 for Mrs. John V. Farwell III of Chicago. The base layer is off-white silk taffeta, with tucked silk chiffon on top forming a slight V-shape down the center front. Yellow taffeta panniers arc out from center back, framing a large bustle of multiple, silk net layers in various shades of green, yellow, and orange.

Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum

Like many of his fashion gowns, the Butterfly, with its enormous bustle, would not have looked out of place in 19th century Paris. Here a model is wearing it in 1954.

Photo by Cecil Beaton and courtesy of the Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s

It was originally designed for Austine Hearst for $1,250, around $13,000 today. It was, according to her recollection, surprisingly comfortable to wear despite its weight and posterior amplitude. In her book, The Genius of James Charles, Elizabeth Ann Coleman says that another owner of this extravagant gown claimed to have bought two opera seat tickets, one for her skirt and the other for the burst of tulle, or “wings,” of the dress.

Tree Ball Gown, 1955

A red, pink and white tulle version of the Tree gown in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., 1981

Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., 1981

Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., 1981

Reshaping the body through corsetry was one of James’ lifelong fascinations, and that quintessential feminine shape is perfected in this 13-pound Tree gown through rigid interior boning in the bodice and intricately tucked exterior hip drapery. According to the V&A Museum, which has one of the gowns in its collection, the inspiration likely came specifically from cuirasse bodices and bustle skirts of the 1870s.

As an added touch of sheer romanticism, the bouffant skirt is faced with rich satin and supported by a profusion of colored tulle, a hidden blossom made visible with movement. James named the design for one of his clients, Marietta Peabody Fitzgerald Tree, and also as a reference to the plant form, which the silhouette, uprooted, resembles.

In a letter to the Victoria and Albert Museum, where Mrs. Tree donated her version of the dress, James wrote: “Mrs. Tree is a large woman; my problem was to reduce a very substantial bust and create a hollow rib cage.”

James further noted that the loosely pleated drapery required tension from the wearer’s body to avoid it appearing “commonplace.” Decidedly uncommonplace, the flounce of the gown in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection, backed with rich white satin, is supported by multiple layers of hidden refinement of red, pink and white nylon tulle.

The layers of pink and white tulle underneath the gown that are revealed with movement.

Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., 1981

James executed numerous versions of this dress between 1955-58 in various colors. Other wearers included Gypsy Rose Lee and Mrs. Cornelia Vanderbilt Whitney.

This pink version of the Tree gown was designed in 1957 and is in the collection of the Chicago History Museum.

Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum

A black version of the Tree gown, also in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. Emmet Whitlock, 1983

In 2014, the Met Museum had a major exhibition of James’ work: Charles James: Beyond Fashion. The retrospective featured around 65 of the most notable designs he produced over the course of his career, from the 1920s until his death in 1978, including his iconic ball gowns. Analytical animations, text, X-rays, and vintage images told the story of each gown’s intricate construction and history, including his Tree ball gown. This animation highlights his approach to garment construction.

You might also like:

Haute Heels: The Mid-Century Shoe Designs of Roger Vivier

Pioneering Fashion Designer Ann Lowe