It was a typical Chicago February morning: gray skies, cold, with a light dusting of snow powdering the city’s sidewalks. But in a dreary garage at 2122 North Clark Street, in a quiet residential neighborhood on the city’s North Side, this Valentine’s Day in 1929 would be anything but ordinary.

The garage, rented by the George “Bugs” Moran gang, which controlled much of the North Side’s illegal booze traffic and ran most of its brothels and casinos, would be the site of one of the most infamous crimes in U.S. history, the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

Al Capone’s platinum Haynes Stellite pocket knife containing 20 single-cut diamonds. The piece is one of 174 lots in ‘A Century of Notoriety: The Estate of Al Capone’ at Witherell’s, October 8. Estimate: $2,500-$5,000

Image courtesy Sheldon Carpenter/Witherell’s Inc.

At the height of Chicago’s gangland warfare, intruders entered the garage, some dressed as cops, lined up shoulder-to-shoulder against the wall seven men associated with Moran, and using Tommy guns and a 12-gauge shotgun, mowed them down in a spray of gunfire.

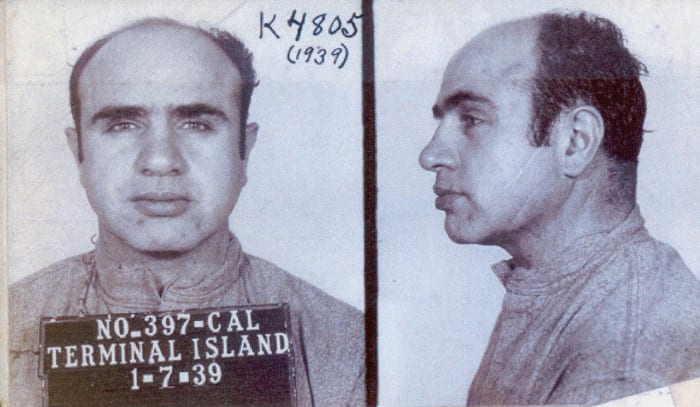

While never officially linked to the massacre, Al Capone, who ruled Chicago’s underworld with an iron fist from 1925 to 1931, was generally considered responsible for the murders. Known as Scarface, Capone was the country’s most notorious gangster during Prohibition, where bootlegging and speakeasies, as well as gambling and prostitution, made him a rich and powerful man. The era also made him the most famous mobster in history.

Chicago gangster Al Capone in 1930 mugshot was known as ‘Scarface’ by many and as ‘Papa’ to his grandchildren.

Photo by PhotoQuest/Getty Images

A 174-lot collection of Capone’s personal and “professional” possessions comes to market via Witherell’s Auction House, Sacramento, California, Friday, October 8. Billed as “A Century of Notoriety: The Estate of Al Capone,” the live-auction event features items showing Capone as a loving family man – a black-and-white photo of Capone and his mother, a personal letter to his son from Alcatraz, home movies – juxtaposed with the tools of his trade – his favorite Colt .45 semi-automatic pistol and a Colt .38 semi-automatic pistol.

Billed as Al Capone’s ‘Favorite .45,’ a Colt Model 1911 semi-automatic pistol. Estimate: $100,000-$150,000.

Image courtesy Sheldon Carpenter/Witherell’s Inc..

Dubbed “Public Enemy No. 1,” Capone died of complications from a stroke and pneumonia in January 1947 in his villa in Palm Island, Florida. He was 48. His belongings stayed in the family and eventually went to his four grandchildren, the daughters of his only child, Albert Francis “Sonny” Capone.

“Well, there’s no question that my grandfather’s name is synonymous with Chicago gangland history,” Diane Capone, one of three surviving granddaughters, said. “And there’s a great deal of information about that to be found in all kinds of history books for that era.

“But what I found lacking as an adult looking back, is that there was very little information about his private life, his personal family life. And so that’s what I wanted to show,” she said.

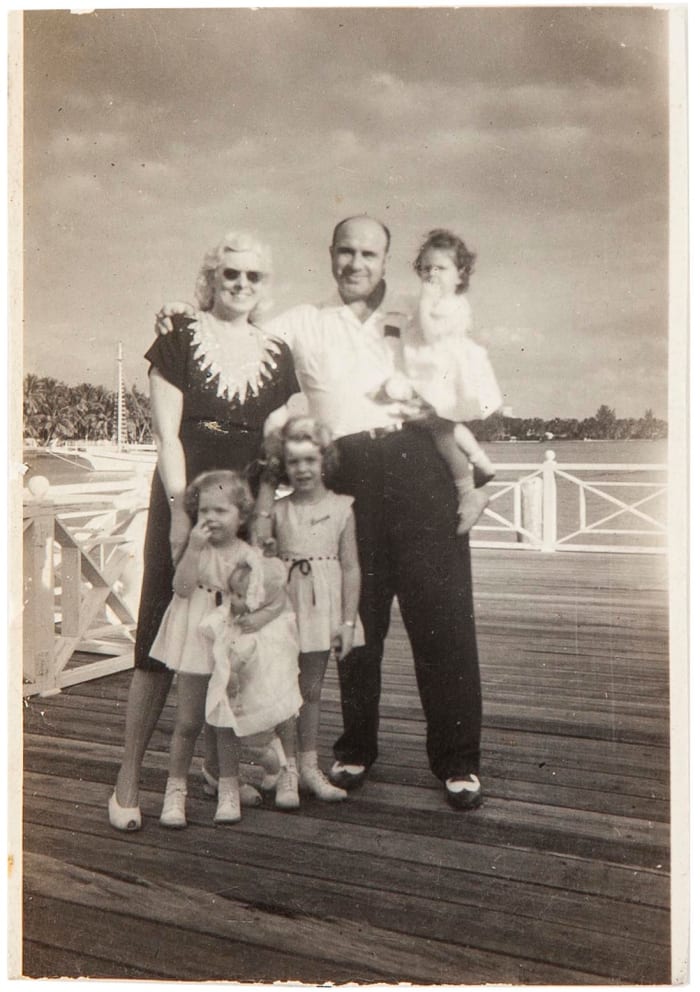

Al Capone and his wife, Mae, with their grandchildren, December 25, 1946. The photograph is thought to be the last picture taken of Al Capone, who died a month later at age 48.

Image courtesy Sheldon Carpenter/Witherell’s Inc.

To the grandchildren, Capone, who is believed to have been behind more than 200 deaths, was known as “Papa” and was “a very loving, grandfatherly figure,” Diane Capone said. “He was somebody who played with us in the garden. He was somebody who would throw us up in the air, and was very affectionate to all of us and very loving, and thought we were just the most wonderful little people in the world.”

Family held for decades, Diane Capone said now was the right time to let go of the memorabilia.

Al Capone’s Patek Philippe pocket watch with 90 single-cut diamonds. Estimate: $25,000-$50,000.

Image courtesy Sheldon Carpenter/Witherell’s Inc.

“My sisters and I are getting older, we didn’t want these things to be left, and people who wouldn’t know what they were, what the story behind each of them is. We didn’t want to leave them for someone else to have to deal with. That was part of our thinking,” she said. “The other thing, quite honestly, is living in Northern California with the fires that we’ve had, I was terrified that if a fire came through, there would be no way that we could save the memorabilia.”

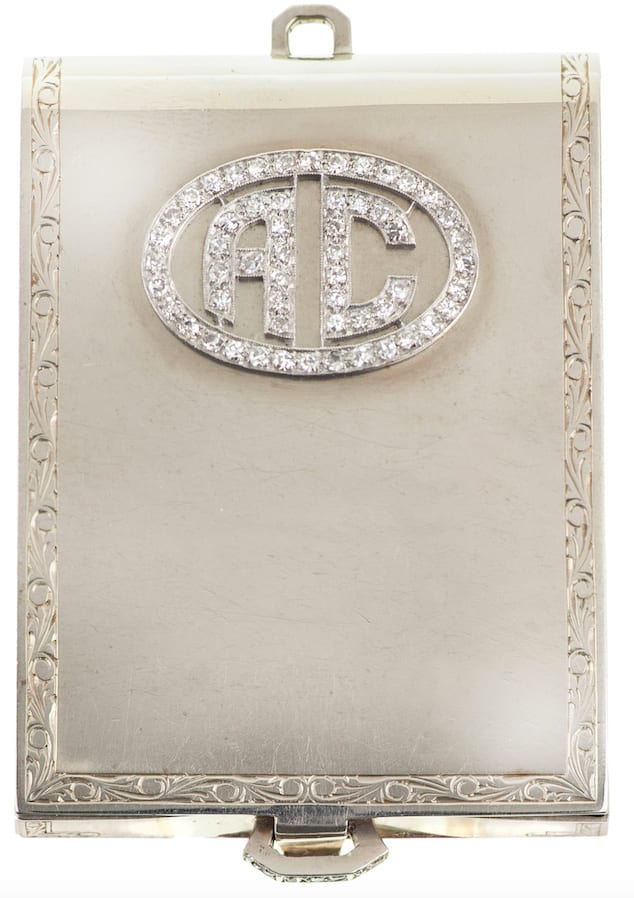

The auction includes furniture, watches, a white-gold matchbook cover Capone used to store matchsticks for his cigars, as well as pieces of Capone’s jewelry, including diamond stickpins and a tie bar with the word “AL” encrusted in diamonds.

Al Capone’s 14k gold and diamond match cover containing 63 single-cut diamonds. Estimate: $2,500-$5,000.

Image courtesy Sheldon Carpenter/Witherell’s Inc.

Capone’s rags-to-riches story as an immigrant son; his criminal life both ruthless and compassionate (during the Depression, he opened a soup kitchen that served up to 3,000 people a day); and a big personality that entertained as well as intimidated, it all remains captivating nearly 75 years after the gangster’s death.

At his height of power, it’s estimated that Capone made $105 million a year and spent roughly a third of it on bribes and muscle — gangsters, judges, politicians, reporters and half the cops in Chicago crowded onto the payroll. With an ever-present cigar and willing smile, Capone was the perfect bigger-than-life Bad Guy.

Capone’s Chicago empire finally crumbled when he was convicted of tax evasion in 1931. He was sentenced to eleven years in federal prison and, after serving some time in jail while his case was appealed, was released in 1939, having served seven years, six months and fifteen days, and having paid all fines and back taxes.

Although believed to be responsible for as many as 200 deaths, authorities could never prove Capone’s guilt. Instead, Capone was sent to prison for tax evasion.

Image courtesy FBI

How history views Capone depends greatly on the perspective of the viewer. Even he was keenly aware of that.

“When I sell liquor, they call it bootlegging,” Capone famously quipped. “When my patrons serve it on silver trays on Lake Shore Drive, they call it hospitality.”