In the 1860s, William H. Mumler was making a good living as a photographer in Boston, Massachusetts but he was no ordinary photographer.

Mumler was a famous “spirit photographer.” People flocked to his studio to get portraits taken of themselves with the spirits of their loved ones, especially after the Civil War. Mumler’s most famous client was Mary Todd Lincoln — and Mumler’s most famous photo is of her being embraced by the purported spirit of her assassinated husband.

Mumler was neither a professionally trained photographer (he had been a jewelry engraver) nor a medium as he claimed, but many grieving people visited his studio and left with hearts full of hope when they saw his photos. His early clients included some of Boston’s most influential families, who came because of either a recent loss or a feeling of nagging emptiness they could not explain. Widows who had seen husbands broken by a disease before death found them whole again. Widowers who missed wives could see their faces again. Parents saw visions of children gone for years.

William Mumler’s photo of Mary Todd Lincoln, with the ghostly figure of her husband behind her and resting his hands on her shoulders.

Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, courtesy of the Indiana State Museum and Allen County Public Library

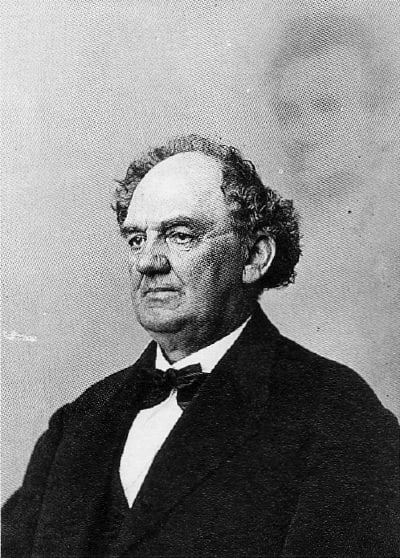

But when Dr. Henry F. Gardner, one of Boston’s leading Spiritualists, noticed that one of Mumler’s captured spirits was of someone still very much alive, the jig was up and Mumler was exposed as a fraud. And he was taken down, in part, by none other than P.T. Barnum, himself a famous promoter of hoaxes. Mumler had also taken a picture of Barnum with the deceased Lincoln.

Ensuing debate about the authenticity of spirit photos also ruined a friendship between renowned Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Conan Doyle and famed illusionist Harry Houdini, who took opposing sides.

But what would make all of those people, including the grieving Mary Todd Lincoln, believe that Mumler could capture the spirits of their loved ones with his camera in the first place? Given the circumstances at the time, this belief was not far-fetched.

In its early days, photography was such a mystery that it was possible for people to believe cameras were capable of capturing ghosts on film, especially since the invention of photography coincided with the beginning of the mid-19th century Spiritualism movement.

The increasing popularity of hauntings, seances and mediums occurring with Spiritualism contributed greatly to the rise of spirit photography and the belief that a camera was a way to connect with the spirit realm. The American Civil War also played a big part in spirit photography’s popularity, as people wanted to get a glimpse of the loved ones they had lost.

Although credited as being the first spirit photographer, Mumler didn’t invent the genre. The first “ghost” photographs were produced by accident in the 1850s and the result of the long exposures required by the earliest photographic processes. If someone getting their picture taken moved during the exposure, they would appear in the final photograph as a blurred, transparent, ghost-like figure.

A photograph that illustrates this effect is a portrait British photographer Roger Fenton took of one of Queen Victoria’s children, Prince Arthur, in 1854. At the side of the young prince is what looks like a ghostly figure reaching out to grab him; in reality, it was his nurse, who had moved into the frame part way through the exposure, likely because she was worried he might fall off the box he was posing on.

Roger Fenton’s portrait of Prince Arthur, 1854, with a “ghostly” figure of his nurse.

Courtesy of The Royal Photographic Society Collection

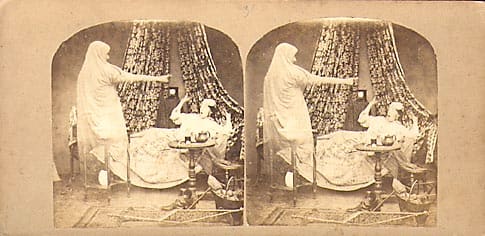

In 1856, esteemed British scientist Sir David Brewster noted this unusual aspect of photography in his book, The Stereoscope: Its History, Theory and Construction: “For the purpose of amusement, the photographer may carry us even into the realms of the supernatural. His art … enables him to give a spiritual appearance to one or more of his figures, and to exhibit them as ‘thin air’ amid the solid realities of the stereoscopic picture.”

Brewster explained how this was easily done: Simply pose your main subjects, then, when the exposure time is nearly up, have the “spirit” figure enter the scene, holding still for only seconds before moving out of the picture. The “spirit” would then appear as a semi-transparent figure.

In the late 1850s, ghost photographs were sold commercially, usually as stereocards. They were produced solely as novelties and amusements and no attempt was made to present them as genuine spirit photographs.

By the 1860s, photographers had developed several techniques to portray ghost-like apparitions through composite images, double exposures and the like. The ease with which these novelty ghost photographs could be made unfortunately meant that the technique was soon used by people to prey on the vulnerable and gullible by taking “spirit”’ photographs of their deceased loved ones.

Enter Mumler, the most famous — and infamous — spirit photographer of them all, who got into the business by accident and with a joke.

In 1861, he was a 29-year-old jewelry engraver living in Boston and enjoyed dabbling in photography as a hobby. In his autobiography, The Personal Experiences of William H. Mumler in Spirit Photography, Mumler explains that one day, while developing a self-portrait, he noticed the mysterious form of a young girl on the negative. He printed this curiosity and showed it around to friends, telling them it looked like a dead cousin. Being of “a jovial disposition, always ready for a joke,” Mumler said, he decided to jest with a spiritualist friend and pretend that his picture was a genuine impression from the world beyond. The friend fell for the gag and cartes de visite of Mumler and his spirit “extra” soon circulated through the city, and news that the first spirit photograph had been taken appeared in The Banner of Light and other spiritualist newspapers. The spirit cousin in all likelihood was no more than the residue of an earlier negative made with the same plate, but it became a revelation, and Mumler, the mischievous jeweler, was heralded as the oracle of the camera.

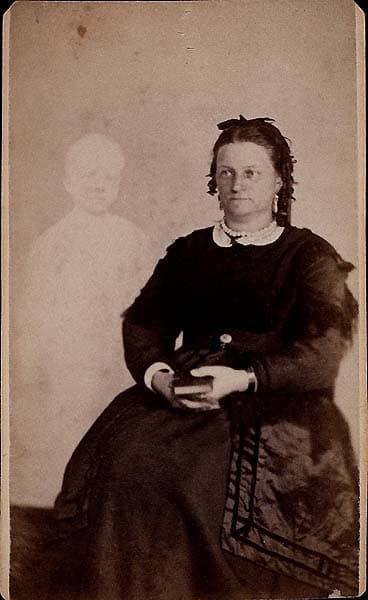

William Mumler’s photo of a client named Mrs. French with a child “ghost.”

Wikimedia Commons/public domain photo

Mumler took advantage of all the buzz and left behind jewelry engraving and opened a photo studio in Boston and later one in New York, billing himself as a “spirit photographic medium.” He mostly serviced those hoping to find a supernatural connection with relatives killed in the Civil War. He sold his spirit photographs between $5 and $10 apiece — which was a huge sum at the time, and he soon grew wealthy off of people’s grief.

Mumler was able to accomplish these spirit photographs with images already made of his “ghosts.” During the Civil War, as families endured separations both lengthy and permanent, keepsake photography became popular, with thousands of portraits produced. One of the most popular forms for these were cartes-de-visite, photographs mounted onto small, thick pieces of paper like trading cards. Mumler used the photos on those cards, along with similar photographs, to create his “ghosts.” He used the visages of famous figures, as in the case of Mary Todd’s and Barnum’s Lincoln portraits, to create the illusion of communion with the notable. And he used images of the non-famous to create the illusion of disembodied intimacy.

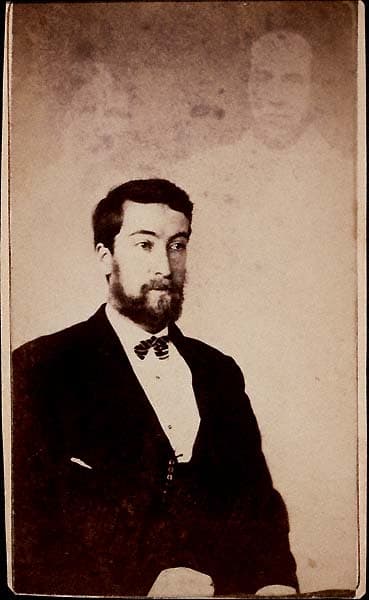

William Mumler’s photo of an unidentified man with two “ghosts.”

Wikimedia Commons/public domain photo

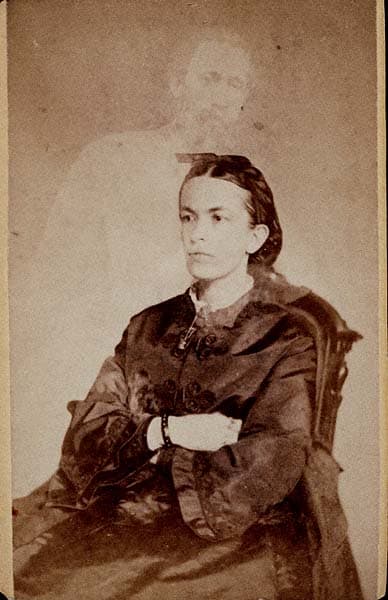

A woman named Fanny Conant with the “ghost” of her brother shown in a photo taken by William Mumler.

Wikimedia Commons/public domain photo

Mumler took advantage of people’s fading visual memories of their loved ones. If a customer shared enough information with him, and if the selected face was faint and blurry enough, the resulting “spirit” could convince anyone who wanted to be convinced.

Doubts started to grow about his work, but even when Dr. Gardner recognized some of the so-called spirits in Mumler’s photographs as Bostonians who were still alive, customers still kept Mumler in business.

Mumler was eventually charged with fraud in 1869, but not just for his fake photos. He was arrested, instead, because of the claims he made about those images — and also because of allegations that he had broken into people’s homes to steal photos of their deceased relatives. Mumler’s ability to create his ghostly prints, he told his clients, was based in turn on his powers as a medium. Mumler and his fellow spirit photographers, including William Hope of England, whose deception was also publicly exposed, preyed on clients’ hope that their loved ones were still present. He told them that, while the human eye couldn’t see their spirits, the camera could, and they believed him.

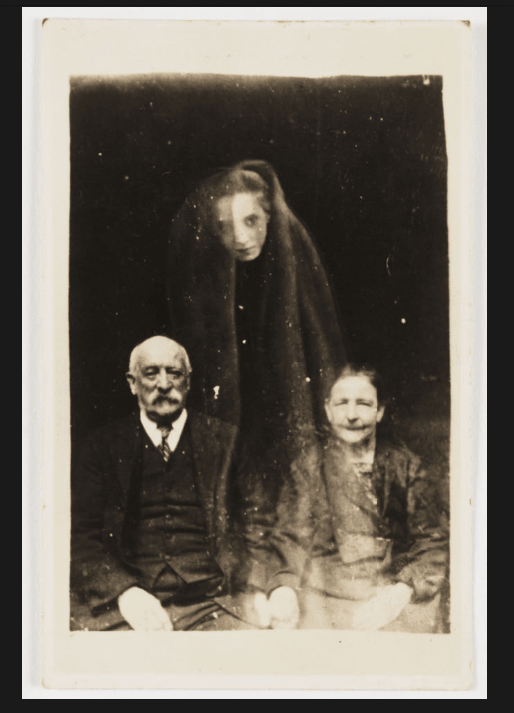

A portrait photograph of a seated elderly couple taken by William Hope around 1920. A young woman’s face appears as if floating above them, draped in a cloak.

Courtesy of the Science Museum Group Collection

Barnum, one of Mumler’s outspoken critics, testified against him, declaring he was taking advantage of people’s grief. Barnum also served as an expert, the Oxford University Press notes, on “humbuggery.”

With Photoshop not being invented yet, Mumler made up for that with his own ingenuity. During his hearing, fellow photographers identified nine different methods that could aid in his photographic imitation of “spirits,” including techniques such as multiple exposure and combination printing.

Mumler’s case was eventually dismissed. Though the judge noted that the photographer likely had, indeed, practiced “trick and deception,” that allegation couldn’t be proven, as there wasn’t enough evidence.

Spirit photography lived on well into the 20th century, fueled in part by World War I. In the U.K., in the aftermath of the first Great War, Hope developed a following for his work that included Doyle, who supported him against claims of “Mumlerian” fraud. Doyle, an outspoken spiritualist who believed that the supernatural could appear in photographs, wrote a book called The Case for Spirit Photography in 1922.

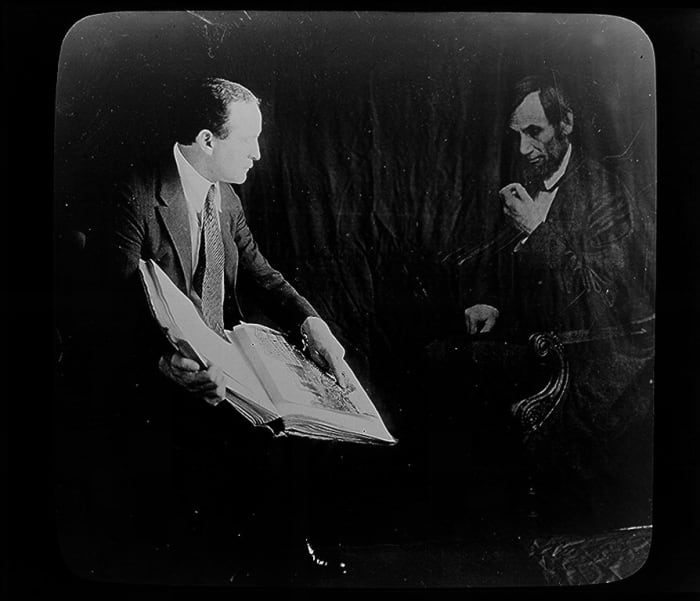

Doyle believed in spirit photography so strongly that he ended his friendship with Houdini when the magician claimed, publicly, that spirit photography was “farcical.” To demonstrate how easy it was to fake a photograph, Houdini had an image made showing himself talking with Abraham Lincoln. He even based entire shows around debunking the claims of mediums and the entire idea of spiritualism.

Harry Houdini and the ghost of Abraham Lincoln, in a photo created by the famous illusionist to debunk spirit photographs. This was published between 1920 and 1930.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Following the court case, Mumler’s New York studio closed from a lack of clients, but in Boston, he remained a popular spirit photographer and advocate of psychic theory. With the failure of the Spiritualist movement in the late-1800s, however, his business suffered again. For nearly three decades, Mumler’s deceptive artistry made him famous and wealthy, but it also nearly destroyed him and he died destitute in 1884.

If you would like to see more of Mumler’s spirit photographs, the J. Paul Getty Museum has his cartes de visite album, which can be viewed here.

![Create a Highly Realistic SKIN TEXTURE in Photoshop! [90-Second Tip #15]](https://mepassions.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/1634808503_maxresdefault-75x75.jpg)