When people in Chico, California say they are “walking the dog,” chances are they are talking about doing a yo-yo trick and not actually walking their pet.

Downtown Chico is yo-yo land and home to the National Yo-Yo Museum founded by Bob Malowney, who also owns the gift shop Bird in Hand that shares a 10,000-square-foot building with the museum. When you hear the cacophony sounds of “whizz,” “swish,” and “zip,” you know you have reached the right place.

Bird in Hand has been fascinating yo-yo fans for decades — holding events, classes, and competitions. You can peruse countless yo-yo models, learn about ancient and contemporary yo-yo history, and purchase one of your own. When Malowney in fact noticed that his customers were more excited to play with yo-yos than any other toy, he was inspired to create a museum devoted to them.

The star attraction of the museum, which opened its doors on January 1, 1993, is the largest functioning wooden yo-yo in the world, “Big Yo.” Not even the strongest of yo-yo-tossing humans can take on this larger-than-life four-foot tall, 256-pound toy; only a giant crane has been able to swing it into action.

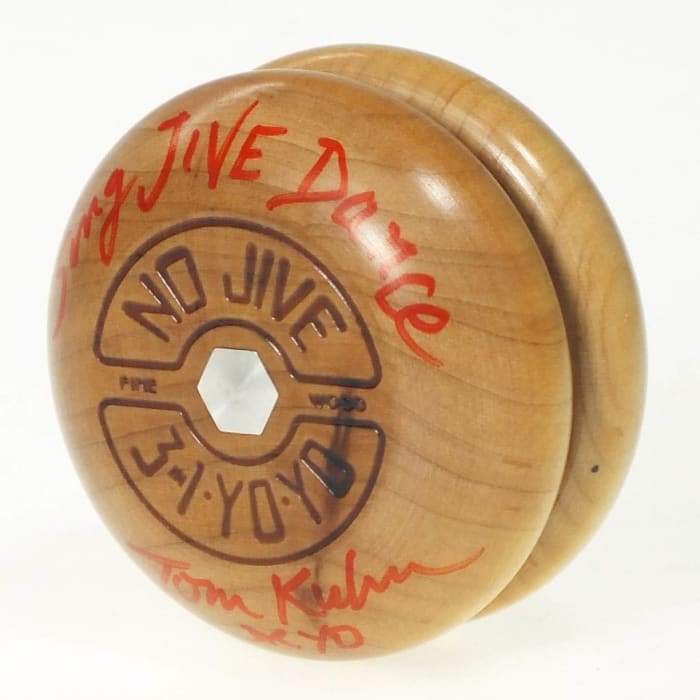

Modeled after San Francisco dentist and yo-yo designer Tom Kuhn’s iconic No-Jive 3-in-1, the gargantuan yo-yo earned its place in the Guinness Book of World Records in 1982 as the world’s biggest working wooden yo-yo.

A Tom Kuhn-signed No Jive 3 in 1 in the museum’s collection. This iconic wooden yo-yo was the inspiration for Big Yo. The first prototype of this yo-yo is also valued by collectors.

Courtesy of the National Yo-Yo Museum

The 600-square-foot non-profit museum houses a colorful array of collectible yo-yos from the last century, including the world’s littlest, the Mighty Flea, which is smaller than a quarter and works just as great.

Fans can learn about the evolution of the toy, from the early wooden ones all the way up to the aluminum ball-bearing models of today. Other display cases hold the yo-yos that highlight the individuals associated with playing the sport and the contests they have won. “The perpetual trophy listing all the modern national champions is here,” Malowney said. Patches and trophies are displayed as well as photos. If it is the actual tricks you want to see, a large video screen shows the various styles of yo-yo plays featured in important contests.

One July Fourth soon after the museum opened, a big celebration occurred on stage and the event holders asked Malowney if they could have a contest for one hour of the program. This drummed up so much excitement that three contests were gradually held every year, he noted.

A display case in the museum of some of the awards won by yo-yo champs. Prizes for competitions in the 1950s, including sweaters and patches, are now collectible.

Courtesy of the National Yo-Yo Museum

When someone in public relations needed a yo-yo exhibit for his company’s malls and asked Malowney for help. he contacted Donald F. Duncan, Jr., the son of Donald F. Duncan, founder of the Duncan Toys Company, which was best known for its line of yo-yos. The two men became friends and did a tour throughout the country called “The Return of the Yo-Yo.”

Malowney said that Duncan was a great showman and taught him that to sell yo-yos was to do simple tricks with a magnificent flair and confidence. They worked together for three years until the exhibit closed. Duncan donated it to Malowney for a four-month exhibit in the Chico History Museum in the fall of 1992. The Smothers Brothers performed there and when the National Yo-Yo Museum opened with the exhibit, they further helped by doing a television promo for it. Tom Smothers, known as “Yo-Yo Man,” created a comedy routine doing tricks with the toy and he and his brother, Dick, have made instructional videos teaching these tricks. A variety of Smothers Brothers-branded yo-yos have also been released by companies including Hummingbird, Playmaxx and Tom Kuhn.

Duncan also gave Malowney the last yo-yo in his drawer when he closed his business: a sad dog, painted with the words, “No Mo Yo-Yo.”

A wooden yo-yo made by the Duncan Toys Company, 1930s. It has a green design with a broad red stripe. The seal reads “Genuine Duncan Yo-Yo, Reg. US Pat.” This is an early version of the Duncan Genuine Yo-Yo, produced soon after Donald Duncan bought the trademark term “yo-yo” from inventor Pedro Flores, and the seal is reminiscent of the one used by Flores.

Courtesy of the National Museum of American History

An original box of Duncan Jeweled yo-yos in the museum’s collection.

Courtesy of the National Yo-Yo Museum

Malowney thrives on yo-yos. He sees the toys every day, making them special to his heart, and nothing makes him smile more than kids beaming from learning a new trick.

The toy is even used as a stress reliever, Malowney said, noting that on June 18, 1815, at the famous battle of Waterloo, soldiers from both sides played with yo-yos before the battle,. and college students will tell him that they will study for 55 minutes, then yo-yo for five minutes to clear their mind. He said that Kuhn, a cerebral person, also found yo-yoing meditative and would call the mindset, “The State of Yo.”

Yo-yoing started way before Malowney, Duncan and Kuhn, though, although nobody knows exactly when.

“Documentation exists that shows people played with a similar spinning toy called a ‘diabolo’ in China around 4000 B.C. Jugglers use it today by the name of the Chinese yo-yo,” Malowney said. “Archeologists unearthed a brass and terra cotta ‘bobbin’ from 500 B.C. in Ancient Greece. They called it ‘bobbin’ because it resembled a sewing bobbin. There are pictures of terra cotta discs and Greek youth playing with yo-yos on pottery in the National Museum of Athens. Europe had them by the 1700s. The English called the toy the ‘quiz.’ The French in the 1800s had a couple of names for them, one of which was ‘incroyable’ (incredible),” he explained.

The yo-yo reached the United States by the 19th century. According to www.ohiohistorycentral.org, the U.S. Patent Office granted the first patent for the yo-yo to Cincinnati, Ohio residents James L. Haven and Charles Hettrick on November 20, 1866. They referred to it as a “whirligig.”

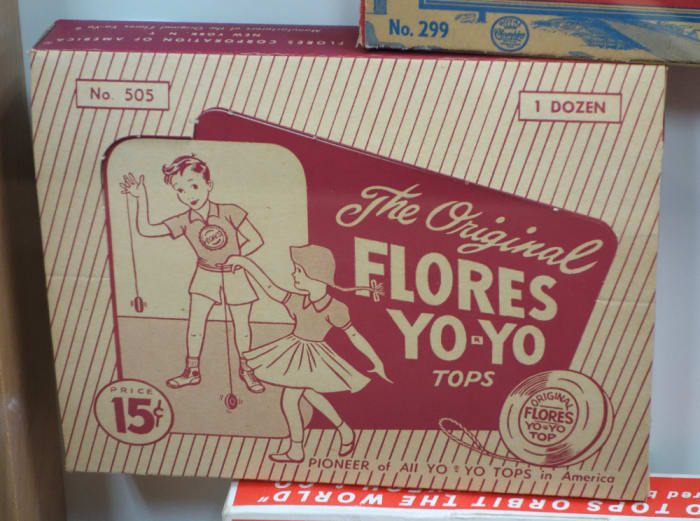

By 1928, Pedro Flores, a Filipino immigrant, trademarked the word “yo-yo” in California. Malowney said that different publications attested that yo-yo in Tagalog meant “come, come” and “come back.” He decided to check the verity of this interpretation with the Filipino Historical Society in the Philippines, which said the word was just created by someone for the toy.

An original box of Flores yo-yos in the National Yo-Yo Museum, which were just 15 cents.

Wikimedia/public domain

Flores sold his trademark to Duncan Sr. shortly after making them for a rumored $25,000. In 1929, Duncan started the Duncan Yo-Yo Company, and both he and Flores marketed their wooden toy with contests and demonstrations on street corners from 1927 to 1945, which the museum considers the Early Era.

The Ohio history website says that approximately 85 percent of all yo-yos in the U.S. during the 1930s through 1960s were produced by Duncan. Eventually the company manufactured 60,000 yo-yos per day, and in 1962 alone, the firm sold 45 million yo-yos worldwide. An early 1930s Duncan yo-yo with a fragile seal decal on the side, gold seal 77, is worth a couple of hundred dollars. More history about the Duncan Yo-Yo company is here.

Malowney said that the museum showcases several 1920s Flores yo-yos crafted from one piece of wood with a thin gap, several 1930s Duncan 77s made from one piece of wood with a tournament stripe, and several Duncan Jeweled, with rhinestones embedded in the side, from the 1940s.

According to Malowney, the golden era of yo-yos was between 1948 and 1962, when Donald Duncan, Jr. and his brother, Jack, took over the company and saw huge sales, helped by television advertising. Wood yo-yos were still in play, but also new plastic ones, and more companies flourished to compete with Duncan. There were also electric light-up yo-yos from the 1950s utilizing penlight batteries (AAA).

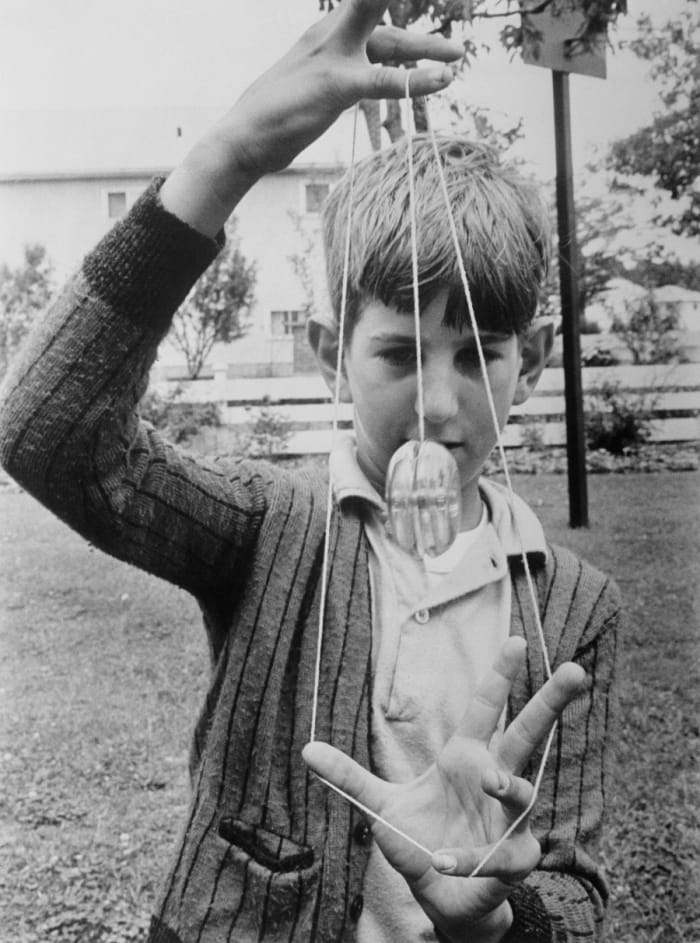

Back in this era of the yo-yo, kids were excited about doing their few tricks to impress their friends. Remember “Around the World,” “Walk the Dog” or “Rock the Baby?” Yo-yoing was fun and an easy, cheap activity, but most people only learned four tricks.

There were also the rejuvenated contests and the engineered aluminum ball-bearing yo-yos, which helps the toy spin with less friction. “The world record for yo-yo spinning is 33 minutes.” Malowney said.

Now the yo-yo is in the Modern Era, which started in 1985, and is the time period of the Kuhn yo-yo. Malowney said that Kuhn “devised and popularized the twist-apart component of the modern yo-yo. The 3-in-1 NoJive can be taken apart and the halves turned around to change the shape of the standard yo-yo and turn it into a butterfly shape to enhance certain tricks.”

Yo-yos have been mesmerizing kids of all ages for centuries. Here, Richard Lee, 9, of North Massapequa, New York, demonstrates the trick, “rocking the baby,”in 1961. Both hands are used to pull the string into a cradle in which the spinning yo-yo is rocked back and forth. It may look easy, but it has to be done quickly so that the top doesn’t stop whirling. Beginners who try it run the risk of tying the string up in knots and their fingers as well.

Bettmann/Getty Images

Kuhn donated a lot of his yo-yos to the museum, including Big Yo, which he created in 1979. Once a neighborhood Duncan yo-yo champion in 1955, Kuhn started designing his own yo-yos in the 1970s. According to his website, tomkuhn.com, one of his creations, the Silver Bullet 2 yo-yo, was sent aloft by NASA on July 31, 1992. It was employed as a prop for an educational video, and Astronaut Jeffrey Hoffman put it through zero G manoeuvres including slow motion yo-yoing. The yo-yo traveled 3,321,007 miles and went around the world 127 times before returning to earth on August 9.

This wasn’t the first yo-yo in space, however. Another one went aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery in 1985 as part of the Toys in Space project. “It would not ‘sleep’ because of the lack of gravity,” Malowney said, “but it performed a beautiful ‘Around the World’ trick.”

Internet sales and instruction have contributed to the revival of the modern era. Some want yo-yos with battery-powered strobe lights and ones that emit sounds, ones that are zippier, faster and more spectacular. Malowney said that a young person today who buys an aluminum yo-yo for $50 won’t even consider putting it on the ground to scratch it up to do “Walk the Dog.” They all want to know tricks such as the “Gerbil” (like a gerbil running along the track in the cage), “Roller Coaster,” “Spirit Bomb” and tons more. If they learn those tricks, they make other ones up.

The love for yo-yos is spreading all over the world. “There are now small companies in Japan, China and Indonesia making yo-yos, even South Africa and in the Arab countries and Russia, excited for competitions,” Malowney said.

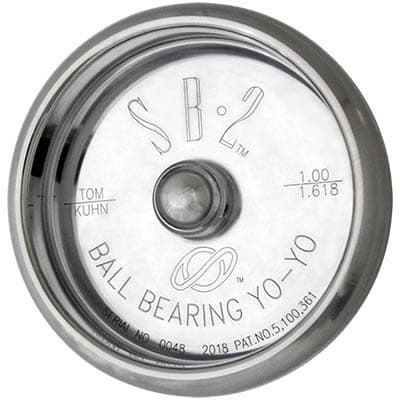

A Tom Kuhn Silver Bullet 3. Kuhn’s ball-bearing Silver Bullet models, which came out in 1984, were the first yo-yos to feature a full-metal body machined out of aircraft-grade aluminum.

Courtesy of the Yo-Yo Museum

World contests happen annually and every third year in the United States — the next one will be in 2023. Next year it will be in Japan. This year it did not take place because of the pandemic. The first modern national competition was held in 1993 and the next one will take place in mid-June 2022 in Mesa, Arizona.

Most Collectible Yo-Yos

The old wooden yo-yos manufactured by Flores in the 1920s are highly collectible because of their rarity and the skill in making them. They are worth hundreds of dollars.

Another extremely rare and collectible yo-yo is the Filipino Twirler from the 1930s. Produced for a short period, it was highly decorated and well-made by an excellent designer who worked for the Long Island, New York, company.

Yo-yos used in contests are also valued by collectors. “Many early contest yo-yos prominently stated on their sidecap what year they were produced. A contest yo-yo may cost $15, but these specialty yo-yos will bring $100 each. Some of these official souvenirs are great collector items,” Malowney said.

He noted that four other of the most collectible yo-yos are the first prototypes of Tom Kuhn’s 3-in-1 No Jive and Silver Bullet, a wood yo-yo imprinted with the signature of American country music singer Roy Acuff, and a prototype YoyoFactory “301” adjustable gap metal yo-yo.

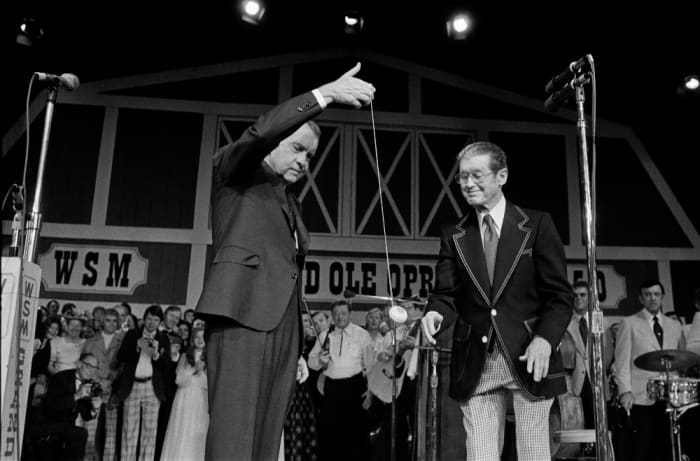

Another valuable yo-yo is the only one signed by a president — the one used by President Richard Nixon when he appeared at the Grand ‘Ol Opry in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1974. Nixon briefly played with the yo-yo given to him by Roy Acuff, the host, and signed it. Last time it was sold, it was bought for $16,000, but presently the owner is not known.

President Richard Nixon demonstrates his yo-yo skills to Roy Acuff at the dedication of the new Grand Ole Opry House in Nashville in 1974. Nixon signed the yo-yo and the last time it was sold, it was bought for $16,000.

David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images

Some newer yo-yos tend to be worth more than the older models because there are more limited-edition ones for specific events. The modern yo-yos still sought after are the early manufactured ones from the leagues in the 1990s.

The museum has one big event every year for National Yo-Yo Day on June 6, just before the end of school and the beginning of summer. The staff gives buttons and holds workshops, teaching tricks to visitors from school-aged children to grandparents who love the sport. It’s an event for the whole family. Malowney said the museum shows contest videos and conducts tours, has free admission and is usually open the same hours as the Bird-in-Hand.

The National Yo-Yo Museum, located at 320 Broadway Street inside Bird in Hand, is open Monday through Saturday from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., and Sunday from 12 to 5 p.m. To learn more about Bird in Hand, visit birdinhand.com.

If you’re interested in yo-yoing, but aren’t sure where to start, world champion Gentry Stein gives a quick tutorial in Episode 1 of his YouTube series, and teaches new tricks in subsequent episodes:

If you are already pretty handy with a yo-yo, champion Harrison Lee explains yo-yo tricks in 26 levels of difficulty:

You might also like:

The World’s Most Dangerous Toy