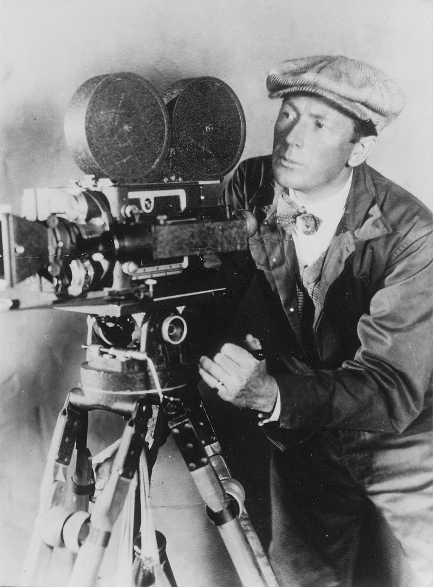

Silents are Golden: Silent Directors – The ingenious FW Murnau

Very large and described with an “icy, imperious character”, FW Murnau fit perfectly into the stereotypical notion of a German silent film director. Highly cultured, his love of the arts and extreme attention to detail resulted in some of the best silent film work – and indeed cinema in general. Some would even say his masterpiece sunrise (1927) is the best film of all time.

The future director of Nosferatu (1922) and The last laugh (1924) was born in 1888 as Friedrich Wilhelm Plumpe in what was then the province of Westphalia in Prussia. He had two brothers, two stepsisters, and his father owned a cloth factory. As a precocious child he liked to play plays in the family home and read Shakespeare, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche insatiable long before he was a teenager.

As a young man, Murnau studied philology in Berlin and then art history and literature in Heidelberg. In Heidelberg he got to know Max Reinhardt, the legendary Berlin theater director who significantly promoted Expressionism. While working in the director’s theater, he took the stage name “Murnau” after a small town south of Munich. After graduating, he stayed with Reinhardt and learned the craft of directing until the First World War broke out. He joined the Imperial German Air Corps and flew numerous missions in northern France. Incredibly, he has been in eight plane crashes and walked away without serious injury each time.

After landing in Switzerland, he was arrested and spent the remainder of the war as a prisoner of war. He never let the time in the internment camp slip by, worked on plays, a script and helped put together propaganda films for the German embassy. By the end of the war, Murnau had decided that film – already one of his obsessions – was his future.

After returning to Germany, he founded a small film studio with the great actor Conrad Veidt (Germany was full of tiny studios at the time). His first feature film was the Gothic story The boy in blue (1919) and his second was Satanas (1920), inspired by DW Griffiths intolerance (1916). He worked with a number of key figures in German Expressionism: Robert Wiene, director of The cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920); Caligari‘s screenwriter Carl Mayer; and set designer Thea von Harbou, wife of the director Fritz Lang, to name just a few.

But while Murnau was immersed in the highly stylized atmosphere of German Expressionism, he had the gift of bringing that atmosphere into the film and at the same time keeping a firm grip on realism. Nosferatu: A symphony of horror (1922) is the most famous example with its dramatically illuminated, macabre story (relish from Bram Stokers Dracula Roman) and real places. Produced by Prana Film, a small studio that wanted to specialize in occult feature films, it built a bridge between the extreme stylization of German Expressionism and the naturalness of films from European countries such as Sweden and Hollywood. Prana Film was forgotten by Stoker’s widow, but that didn’t last Nosferatu

survive and become the classic it is today.

It was believed that Murnau’s The last laugh (1924) caught the attention of Hollywood with its emotional story of a hotel porter losing his station and his incredibly fluid camera work. In reality, Murnau signed a deal with William Fox shortly after the film premiered in Berlin – and long before the US audience saw him. At this point he gained a reputation as a highly skilled director and was possibly recommended by cameraman Karl Freund.

The deal was an undeniable deal: Murnau would have a huge budget, all the Hollywood sets and equipment he needed, and a free hand to take whatever pictures he could think of. But still he meticulously stayed in Germany for a while to create fist (1926), one of his masterpieces. Based on Goethe’s version of the well-known German legend, it contained some of the most notable scenes ever filmed – including the giant demon Mephistopheles standing over a medieval city and causing the black plague (the set used fans and rising soot).

After completing Fist, Murnau eventually went to Hollywood. His first film would be the prestige picture Sunrise, a song by two people (1927), which required sets from a farming village and a huge (or seemingly huge) city street. The latter was created with an ingenious use of forced perspective and attracted legions of cameramen, set designers and designers eager to crawl to see how it was done. It would also use sophisticated cinematography that attached the camera to a rail in the studio ceiling so that it appeared to “float” through a misty swamp. Actors Janet Gaynor and George O’Brien were honored to star in the film, and the production was a special experience for both of them.

sunrise turned out to be a breathtaking achievement and very influential in Hollywood. It would win one of the first Oscars in the “Unique and Artistic Image” category. Many directors (even John Ford) tried to imitate Murnau’s style using dramatic lighting and careful tracking shots. Murnau followed Four devils (1928), which is unfortunately lost today, and the wistful City girl (1929), made as most studios switched to sound film.

Unfortunately, we will never find out what the great FW Murnau would have done with the sound film era, with its initial limitations, but also its possibilities. His last silent film was Taboo: A History of the South Seas (1931), a dramatic love story filmed in Tahiti. Just a week before the premiere, Murnau was chauffeured down the Pacific Coast Highway from Los Angeles. The young driver hit a pole with the car and Murnau suffered a serious head injury. He died the next day at the age of only 42.

…

–Lea Stans for Classic Movie Hub

You can read all of the articles on Leas Silents are Golden here.

Lea Stans is a born and raised Minnesota woman with a degree in English and an obsessive interest in the silent film era (which she largely attributes to Buster Keaton). Not only does she blog about her passion on her Silent-ology page, but she is also a columnist for them Quarterly silent film and has also written for The Keaton Chronicle.