Need a last-minute Halloween costume idea or have been invited to a fancy Victorian dress ball and don’t know what to wear? Fret not. These costume designers have you covered.

The Victorians adored fancy-dress parties: what better way to escape the rigidity of social conventions than to spend a festive evening disguised as Cleopatra, a Swiss milkmaid, Alice in Wonderland, a jester, hen woman, a witch or Hell itself, looking pretty in a pink puffy skirt? Some women also took advantage of Halloween to be a little risqué and scandalously show some ankle or bare shoulders, after being modestly covered from head to toe the other 364 days a year.

Well-to-do party-goers of the era consulted the book, Fancy dresses described: or, What to wear at fancy ball, an elaborate, alphabetical guide to hundreds of glorious costumes written by British author Ardern Holt, who wrote columns on society and fashion, primarily for Queen magazine; and also turned to prolific costume designers Léon Sault and Charles William Pitcher, known as Wilhelm.

Ardern Holt

Fancy dresses described: or, What to wear at fancy ball, first written in the 1879, was so popular that it was updated several times, with the sixth and final edition published in 1896. The costumes are mostly for women, but include a section on children’s dress. Holt also makes suggestions for couples, including Jack and Jill, rooster and hen, any kings and queens, a wizard and witch, night and morning, or night and day.

How to dress like a Victorian witch, according to Holt: You need a red satin quilted skirt, pointed velvet cap, shoes with buckles, black velvet lizards and cats, and a “broom in the hand, with owl.”

Fancy dresses described, or, what to wear at fancy balls

Costumes range from the peasant garb of Austria, Italy, and Ireland to the finery of the six wives of Henry VIII, Marie Antoinette, and other members of French and English royalty. There are also costumes perfectly suited for Halloween, including a couple of witch variations and a goblin outfit for a child.

Additional entries spotlight characters from Shakespeare and Dickens; traditional apparel of Egypt and ancient Greece and Rome; Cinderella, Maid Marian, and other folkloric figures; as well as outfits suggested by astronomy, the seasons, the animal kingdom, and other thematic subjects. Costume designers, reenactors, lovers of Victorian fashion, and Halloween enthusiasts can find these historic volumes a tremendous source of inspiration.

The Hornet: “Short black or brown dress of velvet or satin; boots to match; tunic pointed back and front, with gold stripes; satin bodice of black or brown with gold gauze wings; cap of velvet with eyes and antennae of insect.”

Fancy dresses described, or, what to wear at fancy balls

Holt’s versions of this book over the years got increasingly less conservative as the era progressed. But he was still prescriptive in what you were allowed to wear, from blonde to brunette, old to young and he even insisted your costume had to match your personality:

“It behooves those who really desire to look well to study what is individually becoming to themselves, and then to bring to bear some little care in the carrying out of the dresses they select, if they wish their costumes to be really a success. There are few occasions when a woman has a better opportunity of showing her charms to advantage than at a Fancy Ball,” he wrote.

Some of my favorite costumes featured here are from the fifth edition of the book published in 1887 by Debenham & Freebody: Wyman & Sons of London. The book was contributed to the Internet Archive by the University of California Libraries and is free to download.

This design created by Léon Sault, possibly for Charles Frederick Worth, is perfect for vintage fan collectors, as the theme is a fan. The model carries a fan with black and gold sticks and a purple silk leaf edged with black feathers, which is repeated in the design of the overskirt. Duplicate fans are used as wings on the back of the bodice and as a hair ornament. It is a good example of how elaborate some fancy dress costumes could become when interpreting a simple concept.

Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum

Léon Sault

According to the Victoria and Albert Museum, Sault was a fashion and theater designer and illustrator who later became a magazine editor, publishing some of his fancy dress costume designs as part of a series titled “L’Art du Travestissment” (The Art of Fancy Dress). His designs included characters such as Mephistopheles and embodiments of concepts such as Astronomy.

He also designed a lot of costumes for the great fashion designer Charles Frederick Worth, considered by many to be the father of haute couture and who founded the House of Worth, one of the foremost fashion houses of the 19th and early 20th centuries. During the 1860s, Empress Eugenie of France threw a number of extravagant masquerade balls which required the guests to wear elaborate and inventive costumes that were made up by Worth based on Sault’s designs.

Costume design for a “Hen Woman” by Wilhelm, unidentified production, 1880.

Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum

Wilhelm

Wilhelm was one of the most inventive and prolific late 19th century costume designers, whose early passion for stage spectacle led to his employment designing pantomime costumes for Drury Lane Theatre. His attention to detail and his ability to create visually stunning and decorative costumes appealed to producers and public alike and led to a constant stream of work, according to the V & A Museum.

Wilhelm worked in the prevailing style of late 19th century realism, but with an imagination and flair. It was his knowledge of the techniques of stage costume making, and how to use materials, that made Wilhelm supreme among stage designers.

More Costume Inspiration

This “Goblin” costume for children in Holt’s book calls for “tight-fitting justaucorps of red; red Vandyke tunic; winged hood with cape; fork in hand.”

Fancy dresses described, or, what to wear at fancy balls

Holt said this Magpie costume would be suitable for Calico Balls, in which women were encouraged to wear calico dresses, which could then be given to the poor. This costume is meant to be black on one side and white on the other and has a half black, half white dress, with hair powdered on one side only, one glove and one shoe black, one white. Also features a magpie on the right shoulder and one on the head.

Fancy dresses described, or, what to wear at fancy balls

“Devil” from “L’Art Du Travestissement,” a French fancy dress book by Leon Salut in 1885.

Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum

Wilhelm designed many productions for Adeline Genée, star dancer at the Empire Theatre music hall in the 1890s and early 1900s. Among his last work for her was the ballet, “The Pretty Prentice,” the purpose of which was to show Genée as a mischievous shop girl in as many different moods as possible. This extraordinary creation which he titled, “Eccentric Dress,” is the ultimate Edwardian dance dress, blending imagination and character. A fun dress for a fun character. The stylized feathers on the skirt, to be executed in colored fabrics, silver and sequins, complement the ostrich feather headdress, while the sequined bodice with its enveloping snake, contrasts with the silver and rhinestones and the stiff, pleated “epaulettes” on the shoulders. The silver pantaloons add a delicious touch of naughtiness, so characteristic of the lost Edwardian period.

Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum

This design was created by Léon Sault, possibly for Charles Frederick Worth. It embodies a rainbow. The gray-blue crinoline dress is overlaid with tulle with applied beads to suggest raindrops, and embellished with a large gold sun on the bodice. Another sun forms the headdress, which is overlaid with a sheer tulle veil tinted in rainbow colors. The overskirt is also colored with rainbows, and the model carries a matching fan and wears shoes trimmed with golden suns. While the design is essentially very simple by nineteenth century standards, it is quite effective.

Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum

This design was created by Leon Sault, possibly for Charles Frederick Worth. It is one of the most startling and outrageous costume designs in Sault’s collection. The deep crimson crinoline skirt is decorated with cavorting demons climbing up pitchforks and swinging from ropes, and bats in flight, with an overskirt shaped and patterned to suggest a black lizard skin with gilded scales. An owl in flight forms the wearer’s bodice, and her headdress is a devil with horns and a pitchfork sitting in flames. She wears a veil and matching tulle oversleeves in black, spangled with stars and moons. The costume probably represents Hell, although it could also be “Nightmare.”

Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum

Costume design by Wilhelm for The Winds wearing a gray flowing floor-length robe with a hood and semi-cape, dragon’s wings head piece, spear and metal wind instrument in the pantomime “Dick Whittington,” as performed at Crystal Palace on 24th December 1890.

Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum

A gambling-themed costume, “Monte Carlo”: Half red satin, half black velvet and lace dress; one shoe red, one black; short skirt fringed with coins, and trimmed with cards; pointed coronet of red satin, with aigrette of cards on shoulder; croupier’s rake carried in hand; and Rouge et Noir.

Fancy dresses described, or, what to wear at fancy balls

This design was created by Leon Sault, possibly for Charles Frederick Worth. It depicts a enchantress or sorceress wearing a robe with applied cards over a short white dress embroidered with gold stars and moons and various cabalistic motifs. In addition to this, the wearer wears a high, richly gold-encrusted pointed hat with a sheer veil attached to the point.

Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum

This design was possibly created by Léon Sault for Charles Frederick Worth. Although the specific name of the costume is not known, it is obviously based on games such as checkers (which forms the overskirt), backgammon (the apron) and dice (used as trimmings throughout. The draughts or checkers are also used to trim the borders of the skirt and the bodice. The models’ headdress features a dice-shaker attached to the side of her head, with two dice on strings dangling from it.

Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum

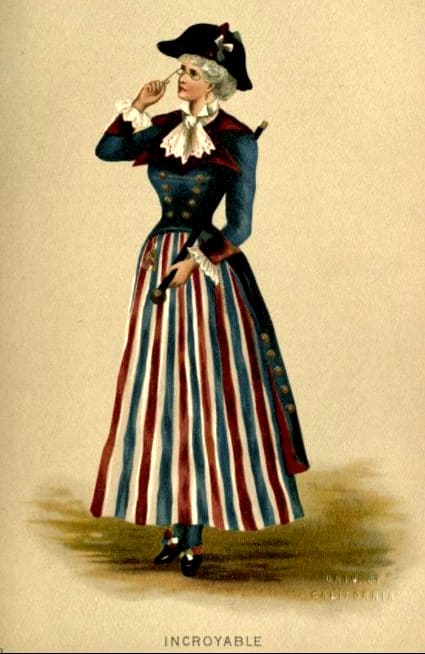

“Incroyable” is another costume Holt recommended for Calico balls and said this is “a very favorite costume,” featuring a short red, white, and blue skirt and blue satin coat with gold buttons. The term incroyable was originally used for fashionable young men in the Paris of the 1790s, whose close-fitting garments in loud stripes with exaggeratedly large lapels and buttons can be seen as an influence here. Holt also recommended an old-fashioned gold-headed cane, fob, eyeglass.

Fancy dresses described, or, what to wear at fancy balls

Holt’s Incroyable costume was likely the source for the design and construction of this fancy dress outfit from the 1890s, made of satin, trimmed with warp-printed grosgrain, lace, braid and metal buttons.

Courtesy of the John Bright Collection