It has been an unlikely yet incredibly rewarding love affair between Carl Heck and Tiffany glass. The artistry and sophistication of Tiffany has captivated the collector, historian and antiques dealer from childhood.

A native of rural Missouri, Heck has bought and sold more than 6,000 stained glass windows and over 150 Tiffany windows including some historic pieces from the Firestone mansion, Coors mansion and a rare lantern from the Cornelius Vanderbilt II mansion.

He has exhibited pieces in 15 museums, including the Corning Museum of Glass, the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, Seattle Art Museum, Dallas Museum of Art, Les Beaux Artes, Montreal, and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, as well as four exhibitions in Japan, and the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris. What’s more, for several years he served as an official Tiffany advisor for seven major antique price guides.

Carl Heck with his daughter, Taylor, on opening night for a traveling Tiffany exhibition at the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris.

Image courtesy Carl Heck

All told, he’s spent decades acquiring Tiffany Studios lamps, windows, mosaics, enamels, bronzes and more. It’s been an impressive journey, especially when you consider Heck started out knowing far more about cattle and corn than he did about the fine glass works of Louis Comfort Tiffany.

And yet, here he is, far from the farm life, living in Aspen, Colorado, an international expert in the field.

“The market has gone insane in the last year. The prices for really high quality pieces have gone to the stratosphere,” Heck says, providing an overview of the Tiffany glass market. “Americans have really discovered Tiffany in the last 10, 15, 20 years and have become extremely interested in his work.”

Early 1880s Tiffany layered window with a rarely seen Tiffany Turtleback tile in the center of the window.

Image courtesy Carl Heck

For example, Tiffany tea screens used to sell for $10,000 to $15,000. Heck noted that last year at auction, Christie’s was getting $120,000 to $140,000 for these pieces that are only four inches tall and nine inches wide. Recently, a rare Tiffany lamp sold in New Jersey. It was projected to bring $50,000 but sold for $3.7 million.

Incredible results, much like Heck’s own story from humble beginnings to one of the most foremost Tiffany glass experts in the country.

It all started on a rural farm in Maitland, Missouri. Growing up in a small town in the northwest part of the state, Heck’s father raised cattle and grew corn and soybeans. Despite the farmhouse’s primitive amenities, Heck had a floral stained glass window above his bed. He’d stare up at it, fascinated by the way it shined with the morning sun.

“I still have that little window,” he says.

Heck’s path from the family farm to his globetrotting adventures of today as an international Tiffany glass expert was paved with determination, risk-taking and the sheer happenstance of being in the right place at the right time.

Image courtesy Northwest Missouri State University

Heck attended Northwest Missouri State University in Maryville, Missouri, and played football and basketball. He earned a Bachelor of Science degree in agriculture and biology but he confesses, never really put the diploma to use. When destiny shines through stained glass windows, Heck discovered, it pays to be flexible.

One Sunday morning in the late 1960s while attending worship services at Maryville Baptist Church with some of his Phi Sigma Epsilon fraternity brothers, Heck learned the church was soon to be demolished. The fate of its 25 stained glass windows hung in the balance. Heck paid a dollar a window, donating the money to the church’s building fund.

“There were a couple of little bitty ones I got way up in the cupola — I had to climb up where all the pigeons lived,” he says. “I had no idea if they were worth 50 cents or $500 or what — I just liked them and thought these have to be saved.”

Heck stored the windows in his father’s barn — much to the elder Heck’s consternation. His father didn’t understand his son’s interest in these “colored windows” that were taking up valuable space in the barn.

Heck finished school and got a job in construction. A Thanksgiving ski trip to Aspen changed the course of his life.

“I saw a lot of stained glass in Aspen and I didn’t think much about it — built into restaurants and old buildings — I came back to Missouri, worked a little longer, saved up some money and that March I hitchhiked all the way from Maitland to Aspen.”

That nearly 800-mile hitchhike paid off. By the early 1970s, Heck had developed a lucrative buying and selling model. He made countless trips back and forth from the Midwest to Colorado selling stained glass windows, furniture and antique quilts.

A view of Heck’s gallery in Aspen, Colorado, showing a rare 1882 Cornelius Vanderbilt lantern as a Tiffany Studios layered Poppy window.

Image courtesy Carl Heck

“We’d wrap the stained glass windows in quilts as packing material,” he said. “We could hitchhike back to Maitland, then we’d buy an old vehicle — school bus, old 1953 Cadillac hearse, old mail truck, pickup truck — fill them, drive them one way to Colorado, sell everything out of the truck, then we’d sell the truck.”

He’d hit up sales in Kansas City and St. Joseph, Missouri. He says people used to advertise glass for sale in the newspapers.

Deciding to make Aspen his home, he went into partnership selling glass out of a store that featured Native American turquoise jewelry, weavings and clothing.

“I started hanging stained glass windows in the windows of the shop that first year,” Heck says. “Then the next year, with another guy, we bought everybody out and took over the upstairs above the shop and put a staircase in and filled the whole upstairs with stained glass windows.”

While he no longer has retail space, when his store was open, it drew a who’s who of clientele, ranging from musicians including members of the Eagles and Diana Ross to movie stars such as Goldie Hawn and director Steven Spielberg. He sold one of the Maryville Baptist Church windows to John Denver’s architect as a housewarming gift for the singer.

A close-up of a Tiffany Studios Poppy window done in copper foil technique.

Image courtesy Carl Heck

After Heck purchased his first Tiffany-made piece in 1975 in St. Louis, he was hooked on the craftsmanship.

Tiffany (1848-1933) was an artist and designer most associated with the Art Nouveau and Aesthetic movements. His father, Charles Lewis Tiffany, founded the jewelry company Tiffany & Co. in 1837.

Coming from wealth, Louis Comfort Tiffany studied art in Europe, but didn’t like the way Europeans painted colors onto glass surfaces. He recruited artisans and glassblowers from Germany, Yugoslavia, Italy and France to work for him back in the U. S. They developed a technique that embedded pigment into the glass and not merely painted its surface.

“They would develop the glass, then designed a window around what it looked like — not the other way around,” Heck says of the process.

Tiffany earned commissions from large churches and wealthy patrons. In 1893 he exhibited a chapel interior at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago that brought him international fame.

Tiffany glass has several characteristics that help collectors differentiate it from imitators. “There’s variations in the glass: ripple (textured), ones made to look like the sky, water, bark of a tree, petals of flowers — thousands of different glass forms,” Heck says.

Tiffany was known for his usage of mineral oxides to color the glass: coppers for greens, cobalt for blues and pure gold dust for the bright reds, Heck notes.

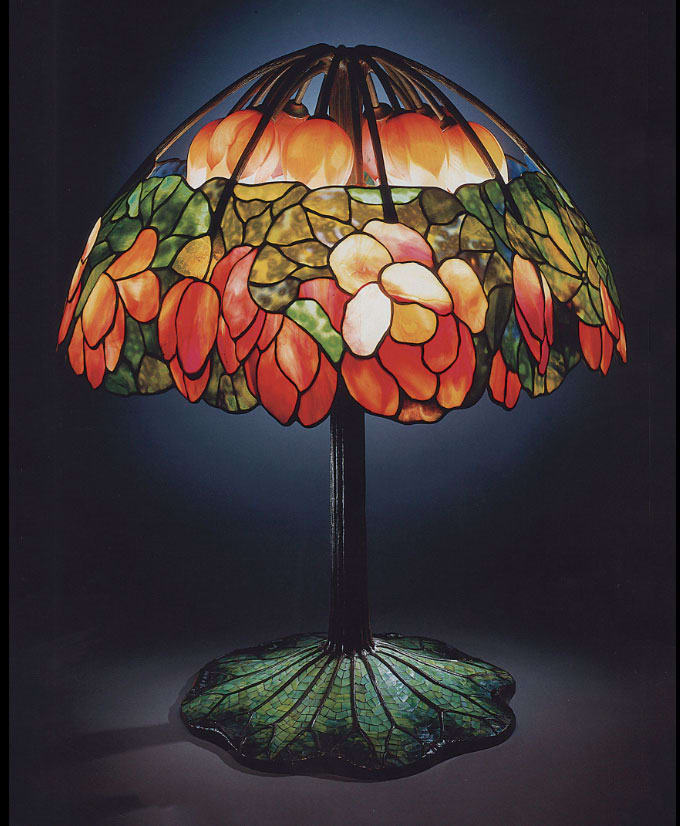

A rare Tiffany Studios leaded glass, bronze and mosaic ‘Lotus’ lamp, circa 1900-1910, sold for $2.8 million in 1997 at Christie’s.

Image courtesy Christie’s

“You always take a piece of Tiffany and look at it in natural lighting and in different types of lighting intensities,” Heck explains. “Tiffany glass changes with every type of lighting change. A lot of the ordinary glass that’s blown today with chemical stains is so flat. It has no opalescence. It has no life. But Tiffany glass is alive. It looks like what it’s meant to look like: a petal of a flower, water with ripples in it.”

Skilled artisans must only make repairs to Tiffany glass. It can be difficult finding the exact piece of replacement glass for a window or lamp.

“Collectors are very particular and they won’t buy a piece that’s damaged unless it’s really cheap,” Heck says.

Tiffany signed some of his pieces with numbers and dashes but many pieces are not marked.

“An old gentleman told me that a lot of Tiffany pieces are not signed, but all the fakes are, and I’ve never forgotten that quote,” Heck reveals. If in doubt, have your glass authenticated by an expert. Heck says he must hold, feel and closely examine a piece before purchasing it. The process of studying an item’s cut and composition can take hours.

But cleaning Tiffany glass isn’t as complicated as one may think.

“Use Windex. You clean them just like normal glass,” Heck says. “But be careful not to disrupt the patina on the lead work — you don’t want that to get shiny and look new. You don’t touch the lead.”

Heck encounters antique glass that endured a variety of environmental conditions.

“I would find in the Rust Belt — there was a lot of industry in those towns — that pollutants adhered to the surface of the glass. Sometimes those windows are extremely hard to clean to get that stuff that’s baked on 100 years,” Heck notes. So familiar with the problem, Heck can sometimes determine in which city a piece was made based on this factor.

While loyal customers and a growing market keep Heck invigorated, he realizes antique glass experts are a vanishing breed. In the early 1970s, Heck would travel to Pittsburgh, Milwaukee and Chicago to visit the old stained glass studios and meet with elderly artisans.

“I would spend hours talking to these guys and learning from them. They were eager to share their knowledge. They understood, because they knew when they’re gone, who is going to know this information? I kind of feel the same way about myself as I get older. Who is going to be the next generation that will share this knowledge of how, why and where these windows were made?”

To learn more about Carl Heck, visit his website at www.tiffanylampswindows.com. He may be reached at 970-948-6667 and carlheck@me.com.

You May Also Like:

Tiffany Lamps: How to Tell Real From Fake

The Hartwell Memorial Window | Artwork Spotlight: In this short video, curators Sarah Kelly Oehler and Elizabeth McGoey and conservators Rachel Sabino and Diane Roberts Rousseau offer insight into the extraordinary window at the Art Institute of Chicago.