In a forgotten storeroom in a fifteenth-century Florentine villa, a pile of Louis Vuitton steamer trunks sat abandoned for decades. When a painting conservator eventually stumbled upon the trunks, what she found inside were not only 38 beautiful gowns, but a lost piece of fashion history was also unpacked, along with the life of Hortense Mitchell Acton, the wealthy American banking heiress who owned them.

The silk labels of twenty-one of the incredible dresses were hand-woven with the name “Callot Soeurs,” the celebrated Paris haute-couture house that was one of the great names in Belle Époque fashion.

Few dresses made by Callot Soeurs have survived, so the gowns that were found moldering inside the trunks in 2004 were a rare and major discovery and the collection is one of the most important archives of the couturiers in the world.

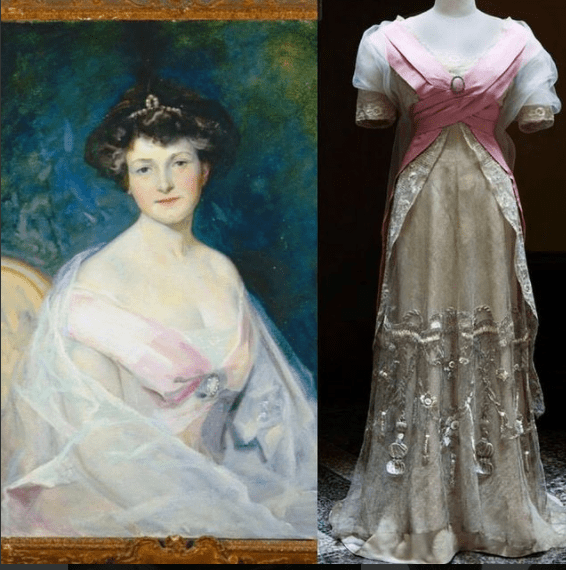

One of the dresses found in the trunks is this pink and cream silk evening ballgown with embroidered metallic net overlay and train, circa 1907. The portrait by Julius Rolshoven is of American heiress Hortense Mitchell Acton wearing the dress.

Courtesy of New York University, Acton Collection, Villa La Pietra, Florence

As the daughters of a painter and a lacemaker, the Callot sisters — Marie Gerber, Marthe Bertrand, Régine Tennyson-Chantrelle, and Joséphine Crimont — opened their first shop in Paris in 1879. Their business thrived selling the lace, ribbons, and lingerie that were coveted for the ornately detailed fashions of the era. By 1895, their success and acquired investment by wealthy benefactors led their business to expand into a couture house under the name Callot Soeurs (the French word for sisters). After losing Joséphine to suicide in 1897, Marie, Marthe and Régine continued to run the business. Their reputation grew rapidly throughout Paris, and the 1900 Paris Exposition introduced them to international clientele.

One of the Louis Vuitton trunks the dresses were found in. In the Acton collection at Villa La Pietra, there are ten original trunks, four of which have been displayed as part of a temporary exhibition on the subject of fashion and lifestyle in the 1920s. These trunks speak not only to the incredible wealth of the Actons, but also to their globalized, cosmopolitan lifestyle.

Courtesy of New York University, Acton Collection, Villa La Pietra, Florence

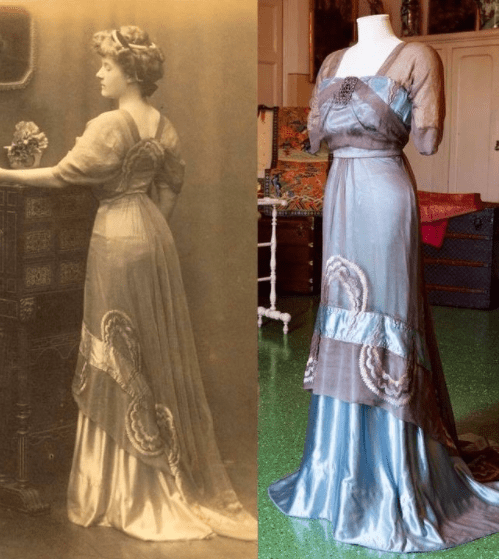

In this photograph of Acton taken by H.A.V. Coles in Paris in 1909, she is wearing a Callot Soeurs’ pale blue silk satin and gray chiffon two-piece evening dress that was found in one of the trunks.

Courtesy of New York University, Acton Collection, Villa La Pietra, Florence

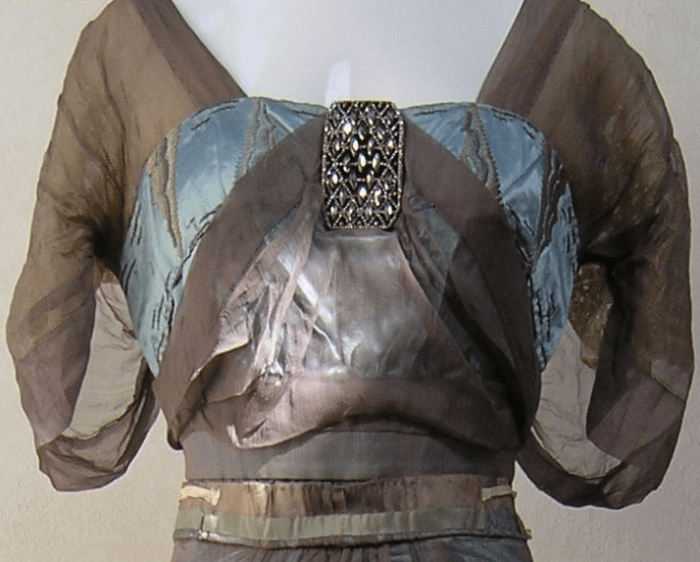

A closeup of the marcasite ornament on the blue and gray dress.

Courtesy of New York University, Acton Collection, Villa La Pietra, Florence

The label became known for its resplendent and romantic gowns, highly ornamented creations of weightless layers inspired by the Near and Far East. The sisters also abandoned corsets, instead favoring the S-curve of the 1890s for a more natural feminine shape.

Vogue magazine called them the Three Fates, and declared they were “foremost among the powers that rule the destinies of a woman’s life and increase the income of France.”

A pale pink and black silk evening dress composed of a bodice and a skirt, with gold trim and black velvet belt. A black lace overlay covers the shoulders and the skirt; circa 1910-12.

Courtesy of New York University, Acton Collection, Villa La Pietra, Florence

A textile conservator uses a professional humidifier to treat the pink and black dress, releasing creases by directing moisture.

Courtesy of New York University, Acton Collection, Villa La Pietra

Callot Soeurs is regarded as the vanguard of Belle Époque fashion, and set the standard for elegance at the beginning of the twentieth century. The sisters’ creations became a staple in the wardrobes of society women throughout Europe and the United States, helping to usher in a new era of fashion.

One of these society women was Hortense Mitchell Acton, who owned these dresses, along with the villa they were found in: La Pietra.

Built by a Medici banker, the 62-room Villa La Pietra, located in the hills outside of Florence, Italy, was bought in 1907 by Acton, a Chicago heiress who was married to Arthur Acton, an English antiques dealer and art collector.

Acton was a faithful client of Callot Soeurs and bought the sisters’ designs from the first time they opened their doors until they closed them in the 1930s. The surviving custom-made gowns reveal the complexity and lightness of the Callots’ designs, their craftsmanship and innovation, and their knowledge of materials, including two of their favorites they were among the first designers to use — lace and lamé.

Gold lamé and cream silk evening dress with short sleeves, gathered gold waistband and lace upper bodice, the underskirt also with lace trim. Label “Callot Soeurs. Paris,” 1910-12.

Courtesy of New York University, Acton Collection, Villa La Pietra

Detail of the gold lamé and cream silk evening dress.

Courtesy of New York University, Acton Collection, Villa La Pietra

With La Pietra as her opulent stage, Acton wore her Callot Soeurs gowns to the parties she regularly hosted. Her lavish soirees drew important writers, artists, politicians, actors and members from the cosmopolitan milieu. Everyone from Gertrude Stein and Sergei Diaghilev to Winston Churchill attended these parties.

When the Fascists rose to power in Italy in the 1920s, most of Florence’s expatriates packed up and left. Hortense wanted to leave as well, but her husband insisted on staying for the sake of the villa and his collections. In 1940, the police arrived at Villa La Pietra and confiscated its contents (overlooking the dresses). Being an American, Hortense was considered a hostile foreigner and she was jailed, but she and her husband eventually escaped to Switzerland. When Hortense died in 1962 at age 90, her gowns were still locked away.

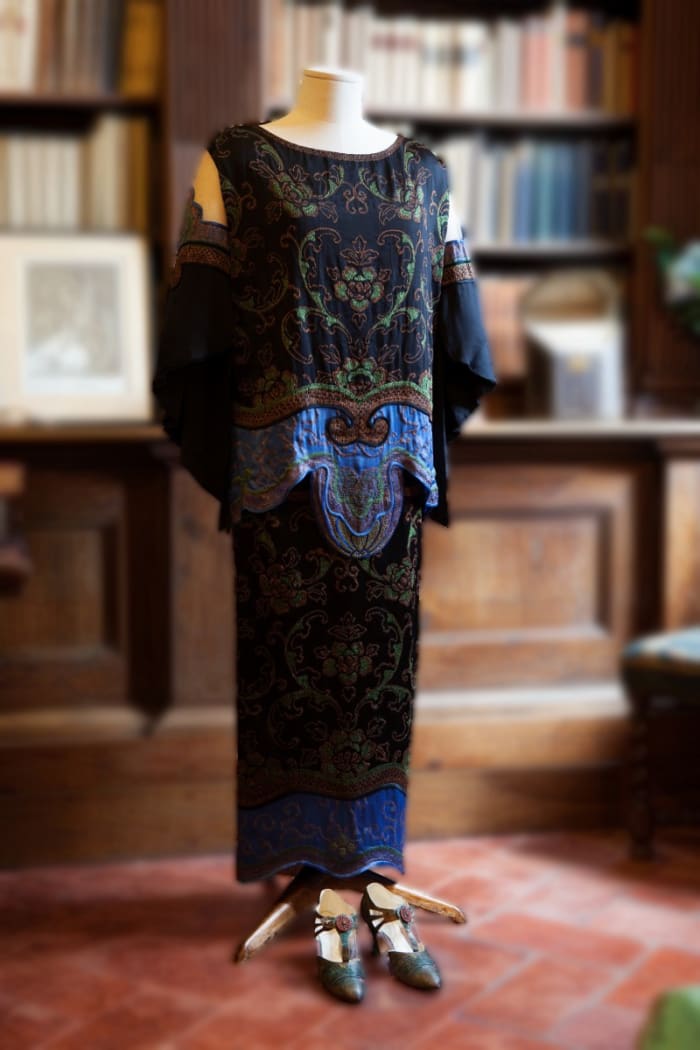

Hortense’s passion for the Asian world was an interest that began when she was a child in Chicago, and many of her Callot Soeurs’ dresses show influence from Chinese costumes. This pink and green silk dress from the 1920s is a more obvious example of this. The cut (emphasis on the black lace bat wings and loose-fitting design) and embroidered details of the fabric (which is likely directly from China) are examples of how the Chinese style influenced the design. Passementerie tassels composed of rhinestones, pearls and beads that hang from either shoulder.

Courtesy of New York University, Acton Collection, Villa La Pietra, Florence

Hortense Mitchell Acton is wearing the green and pink Callot Soeurs’ dress in this photo from the 1920s.

Courtesy of New York University, Acton Collection, Villa La Pietra, Florence

New York University was bequeathed La Pietra in 1994 by the Actons’ son, Sir Harold Acton, the Oxford memoirist, historian, and aesthete, who had tucked away his mother’s gowns in the steamer trunks. When they were discovered in 2004, they were in good condition for being so old, but chemicals from glass beads leached into fabric, sequins deteriorated, embellishments tore the tulle they adorn and repeated wear embedded wrinkles.

Three-piece black and blue satin day dress with bat-wing sleeves and embroidery, Callot Soeurs, 1920s.

Courtesy of New York University, Acton Collection, Villa La Pietra, Florence

Dated 1929, the university says that this floral print silk (lamé) Callot Soeurs’ cocktail sheath dress, with an extravagant pink rose on the hip, is an indication of the glamorous lifestyle Hortense Mitchell Acton enjoyed at Villa La Pietra.

Courtesy of New York University, Acton Collection, Villa La Pietra, Florence

After a survey and conservation treatment to make them stable for temporary display, five of Hortense’s rare and expensive Callot Soeurs dresses are now presented to the public at Villa La Pietra. In NYU’s online exhibition, these dresses represent different fashion styles between the early 1900s and 1930s. The fashions are put into context of five different rooms of the villa to give visitors the opportunity to get to know Hortense Mitchell Acton through these dresses and accompanying artifacts.

Acton’s well-loved pink and cream silk evening gown, for example, is representative of the early stage of her life at La Pietra. It can be dated around 1907, when her portrait by the Detroit painter Julius Rolshoven was commissioned and displayed in the villa.

Acton’s well-loved pink and cream silk evening gown.

Courtesy of New York University, Acton Collection, Villa La Pietra, Florence

Detail of the metallic net overlay of the pink and cream silk evening gown.

Courtesy of New York University, Acton Collection, Villa La Pietra

With her husband, Hortense shared an appreciation for the arts and kept many noteworthy artists within her network such as Jacques-Emile Blanche, William Merritt Chase, James Montgomery Flagg and Paul César Helleu. These important artists’ work can also be found throughout the collection today. The painting by Rolshoven is the only portrait in the collection where Hortense is wearing one of the gowns from her haute couture wardrobe.

Today, Callot Soeurs’ legacy remains understudied, but the couture house is still widely recognized and its fashions collected, and the sisters’ designs feature prominently in museum collections worldwide and perform well at auction.

Although they require great care and are challenging to preserve because of the array of different materials the sisters used in making them, the 21 lavish Callot Soeurs’ gowns continue to live on in a room on the villa’s fourth floor.

To learn more about Acton’s life and see more in the collections, visit Villa La Pietra.