Robert L. May was down in the dumps. It was early 1939 and the life May was living was not what he had hoped for.

A copywriter for the retail and catalog giant Montgomery Ward in Chicago, May (1905-1976) was almost 35, heavily in debt and grinding out catalog copy. “Instead of writing the great American novel, as I once hoped,” May would later recall, “I was describing men’s white shirts.”

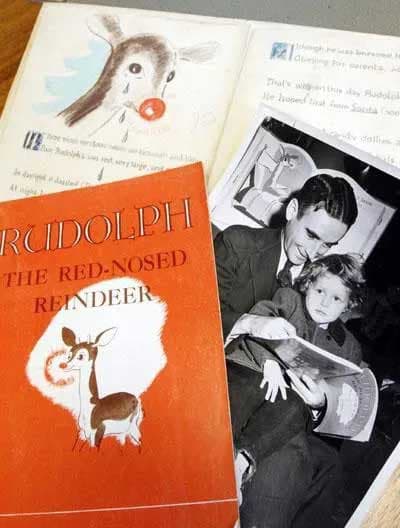

A first edition of “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” (bottom) with an original layout (top) from the Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth College. The library houses a large collection of Rudolph-related materials.

Shutterstock

To make matters far worse, his wife was suffering from a long illness, one that would eventually take her life. Things were so bad that he felt relief going to work on a blustery cold January day, seeing that holiday street decorations surrounding Montgomery Ward had been taken down.

Finally, he thought as he trudged into work, no more faking the merry-and-bright routine the season often requires.

It’s funny how quickly a life can change, even during its gloomiest moments. May was about to find that out for himself.

Each year, Montgomery Ward created a free coloring book for children as a Christmas promotion. May’s boss asked him to take a swing at creating a brand-new character for the giveaway.

Considering the circumstances, the timing could not have been worse. Or, perhaps, better.

A first edition of “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” a photo of Robert May with his daughter, Barbara, and an original layout, are part of a special collection at Dartmouth College, donated by the estate of Robert May.

Shutterstock

What emerged from the bleakness of May’s personal life was a story of an outcast reindeer, one who was teased incessantly for having an abnormally large, shiny red nose. So shunned, the small reindeer couldn’t even play in any reindeer games. But then, one foggy Christmas Eve, Santa came to call, and … well … you know the rest of the story.

More than 2.4 million copies of May’s tale of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, illustrated by Montgomery Ward colleague Denver Gillen, were handed out to children that first year.

A small publishing house, Maxton Publishing Co., offered to print the story in hardcover. It became a best-seller. Even so, Rudolph’s story didn’t become world-famous until May’s brother-in-law, Johnny Marks, wrote the musical version that Gene Autry sang. Released in 1949, “Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer” hit No. 1 on the U.S. charts the week of Christmas. It would go on to sell more records than any other holiday song other than Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas.”

Rudolph’s story was told anew in 1964 as a stop-action animation TV special on NBC. Narrated by Burl Ives, the TV Rudolph is now considered a holiday classic.

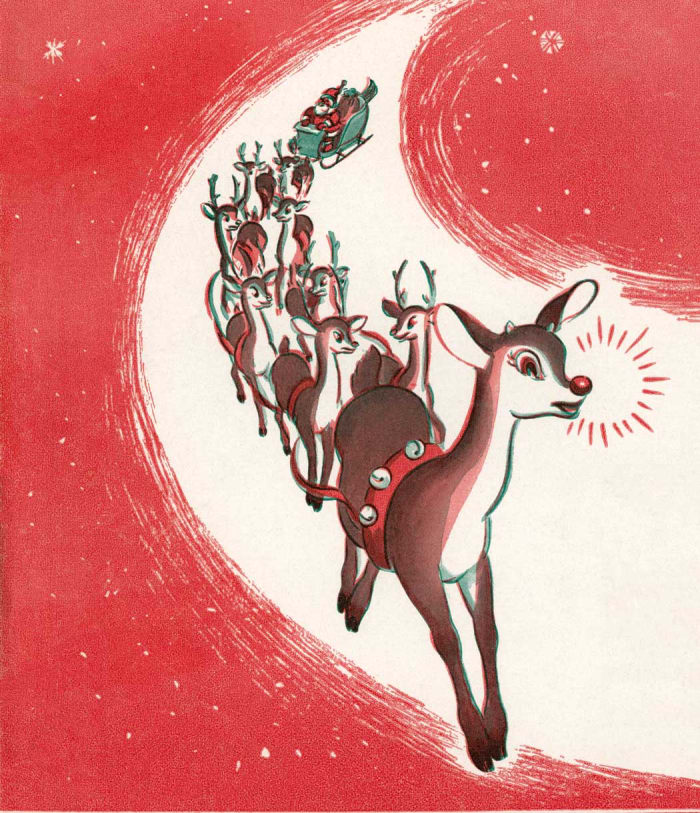

On a foggy Christmas Eve, Santa asks Rudolph to guide his sleigh in the 1964 stop-action animation TV special.

Courtesy Classic Media

May’s story, beloved by generations, was inspired by the story of the Ugly Duckling, which May said always appealed to him. May grew up shy and small. He knew what it was like to be an underdog.

As for Rudolph, May figured his story should be about a reindeer because everyone was already familiar with them. It also helped that his toddler daughter, Barbara, adored the deer at Lincoln Park Zoo. Thanks to the 1820s poem, “A Visit from Saint Nicholas,” Santa’s reindeer already had names — Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Donner and Blitzen. May added a ninth..

For alliterative purposes, he considered Rodney, Rollo, Reginald and even Romeo. In a 1963 interview, he said he thought Rollo sounded “too happy for a reindeer with an unhappy problem” and Reginald “seemed too sophisticated,” but Rudolph “rolled off the tongue nicely.”

The idea for a glowing nose? That light-bulb moment came from looking out his office window on a winter’s day, watching the fog roll in from Lake Michigan and wondering how Santa would navigate such a night.

Illustration of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer leading Santa Claus’s sleigh on Christmas Eve, 1949.

Photo by GraphicaArtis/Getty Images

How May navigated the following months was remarkable.

In July of 1939, his wife passed away. May’s boss kindly offered to have someone else finish the project. But by now, May needed Rudolph more than ever. He buried himself into his writing.

Before submitting the story, he read it to his daughter and his in-laws. “In their eyes,” May said in 1975, “I could see that the story accomplished what I had hoped.”

It had done for others what it had done for him.

In the darkness of Robert L. May’s life, there was light. Not unlike Rudolph’s own shiny nose, you could say that light still glows.