The art of enameling has been practiced for thousands of years and by all the great cultures in all parts of the world. The ancient Egyptians, Chinese, Romans, Georgians and Celts all practiced different forms of enameling.

Today, most people are familiar with the less artistic, commercial types of enameling such as those seen on cooking implements, sinks, bathtubs and other appliances. Perhaps the most widely-known examples of enameling are the famous Fabergé eggs made by Peter Carl Fabergé.

The jewel-like colors seen in enamel are achieved by grinding colored glass into powder that is heated to form a paste then further heated until it liquifies and is fixed to a base material. Another method is to melt colorless glass and add pigment.

Enamelwork is liquified glass in a variety of colors that, with the aid of heat, is applied to a range of materials, with metal such as bronze, copper and brass being the most common base for application. Almost any surface that can withstand the high temperatures necessary for fusing can be used, including a variety of metals and stone. Ceramics and even glass can be decorated with enamel although the application process is quite different; the enamel is painted on rather than fused. Enamels exist in three basic clarities: opaque (not transparent), opalescent (semi-transparent) and transparent.

Champlevé, cloisonné, niello, guilloché, gripoix, taille d’epergne, basse taille, vitreous enamel, plique-à-jour, shippou-zogan and cold painting are different types of enameling that are often misidentified, yet easy to distinguish. With the exception of Basse Taille, these types of enamels are readily available in the antiques marketplace, which is why it is important to be able to distinguish one from the other.

Shakespeare penned a brilliant line for Juliet when he wrote, “… What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” Shakespeare aside, in the world of antiques, names are important; they can be descriptive, and they mustn’t be confused. You may call a rose a gym sock and it would still smell as sweet, but you cannot call champlevé anything but champlevé. If you call it cloisonné, niello, guilloché, vitreous enamel or plique-à-jour, you’re making it something it is not. You can hold up a rose and call it a gym sock and people will still know it is a rose, but if you misidentify champlevé as cloisonné, people are going to believe you and may even purchase it thinking they are buying cloisonné. Although champlevé and cloisonné are both types of enameling, the method employed and the end products are extremely different.

And of all these enameling techniques, it is champlevé and cloisonné that are most often confused and misidentified.

Champlevé is an enameling technique whereby depressions that are incised, carved or die struck on the surface of metal objects are filled with opaque enamel and then fired until the enamel is fused with the base metal.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

Champlevé

Champlevé is an enameling technique whereby depressions that are incised, carved or die struck on the surface of metal objects are filled with opaque enamel and then fired until the enamel is fused with the base metal. The troughs or depressions in the metal object may also be cast when the piece is created and then filled with enamel, cooled and polished. The original, uncut metal surfaces form a frame-work for the enamel.

The word champlevé is a compound French word (champ + levé) meaning “field raised” or more precisely, raised field. This is a source of confusion for many who argue that the field is not raised but rather hollowed out before being filled with enamel. I like to think of it as the areas of depression being raised by filling them with enamel. Champlevé is quite satisfactory for decorating large items such as chargers, vases and plaques.

The enameling in cloisonné is overall, whereas the enameling in champlevé is done in well delineated areas. In this pair of large cloisonné vases, the base metal is clearly visible at the base and rims.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

Cloisonné

Cloisonné, a term originating in France during the mid-19th century, is distinguished from champlevé in that with cloisonné, the areas meant to be filled with enamel are not incised into the metal. The compartments, or cloisons (French for partitions) are formed by soldering flat metal strips to the base metal in precise patterns. The unfilled cloisons give the appearance of a maze. These areas are then filled with colorful, opaque enamel to form designs or images such as animals, people, flowers or even geometric patterns. The enamel begins as a powder, it is made into a paste and applied, then fired. The enameling in cloisonné is overall, whereas the enameling in champlevé is done in well-delineated areas.

Although cloisonné is most closely associated with China, it did not originate there. In fact, cloisonné originated in Western Asia, most likely in Byzantium, an ancient Greek colony in present day Istanbul, and did not reach China until the 14th century. The earliest pieces of cloisonné are seen in jewelry and small pieces such as knife handles and fastenings for garments rather than the larger pieces we associate with cloisonné today.

In his article, “The Earliest Cloisonné Enamels from Cyprus,” in The Enamellist’s Magazine, April 1989, Panicos Michaelides identifies the earliest known pieces of cloisonné as rings from the 12th century B.C. found in present day Cyprus. Although cloisonné did not originate in China, some of the best examples were made there. The most valuable Chinese cloisonné is from the Ming Dynasty. Many fine examples of Chinese cloisonné from the mid-19th century can be found today. During the mid-19th century, many high-quality pieces, known as shippo-yaki, were also made in Japan. Cloisonné is still being produced today in China as well as Japan. During the 18th and 19th centuries, cloisonné was produced throughout Europe with designs based on Chinese motifs.

Two European variations of cloisonné not discussed here, but which may be of interest to those who collect enamels, are known by their German names: Vollschmelz (full melting) and Senkschmelz (sinking or sunk melt). Simply stated, in Vollschmelz, the entire inner surface of a bowl or plate for instance is divided by wires and covered in enamel, whereas in Senkschmelz, depressions are made on the inner surface of a bowl or plate and only these depressions (or sunken areas) are filled with enamel.

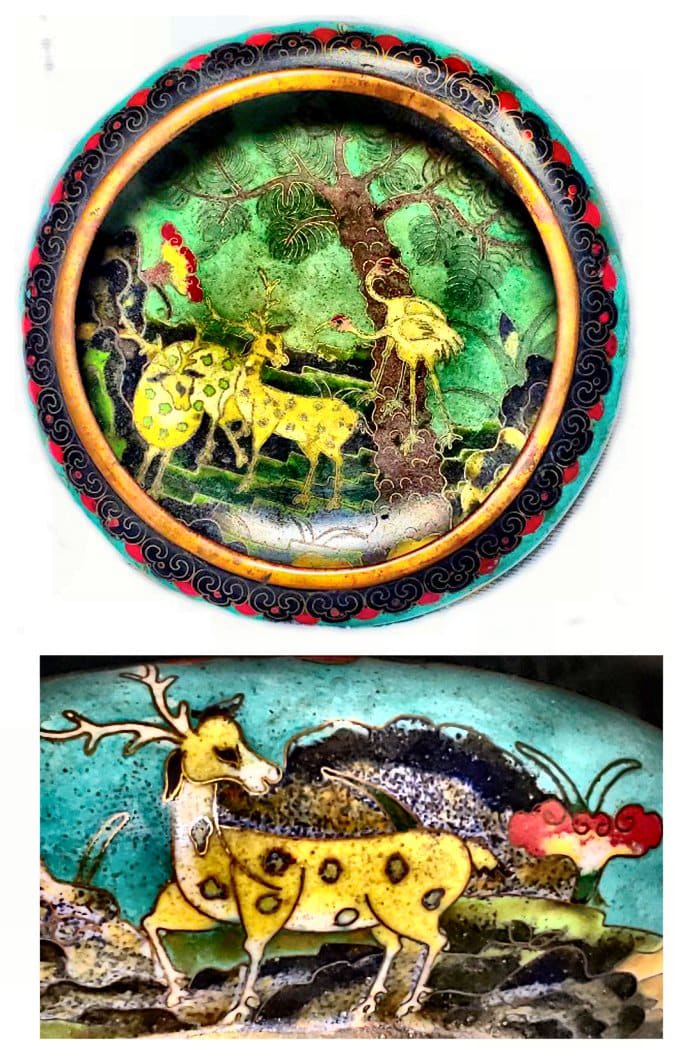

Objects made of Cloisonné are not limited to decorative pieces. The beautifully crafted Chinese cloisonné bowl below is a 19th century brush pot used for washing calligraphy and artist’s brushes. Not only is this beautiful piece utilitarian, it is decorated with deeply symbolic images. The pot is decorated both on the inside and outside with: deer (longevity and wealth), cranes (longevity and peace), butterflies (immortality and conjugal bliss) and pine trees (longevity, solitude, steadfastness and marital bliss) the predominant color, green, is symbolic for harmony, wealth and growth. The image at the bottom of the photo is a detail from around the outside of the pot. The detail the artist was able to achieve is so fine it appears like a painting rather than brass partitions filled with enamel.

Objects made of cloisonné are not limited to decorative pieces. This beautifully crafted Chinese cloisonné bowl is a 19th century brush pot, used for washing calligraphy and artist’s brushes.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

The motifs used in cloisonné are typically derived from nature, with each image being symbolic in addition to decorative. The colorful cloisonné box below, with a green jade knop, depicts a variety of flowers and butterflies. The peonies, the floral symbol of China, symbolize riches, honor, good fortune and a happy marriage. The butterflies symbolize immortality, grace, conjugal bliss and romanticism.

This cloisonné box with a green jade knop depicts a variety of flowers and butterflies. The peonies, the floral symbol of China, symbolize riches, honor, good fortune and a happy marriage. The butterflies symbolize immortality, grace, conjugal bliss and romanticism.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

The Differences

Champlevé and cloisonné objects of roughly the same size will differ considerably by weight, with the champlevé weighing more due to the thick metal base required for carving. A combination of cloisonné and champlevé can be found in a single piece. These pieces open the door to interesting discussions as to whether a piece is cloisonné or champlevé.

Champlevé and cloisonné objects of roughly the same size will differ considerably by weight, with the champlevé weighing more due to the thick metal base required for carving. The base metal in champlevé (shorter vase on the right) is apparent overall, while the base metal in cloisonné (taller vase on the left) is usually visible at the base, rim and interior; the small partitions in cloisonné are clearly visible on close examination. This image compares a ten-inch cloisonné vase with a nine-inch champlevé vase. Although the champlevé vase is shorter by an inch, it weighs a pound more due to the thickness of the base metal.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

A combination of cloisonné and champlevé can be found in a single piece. These pieces open the door to interesting discussions as to whether a piece is cloisonné or champlevé. Below are examples of pieces some would identify as cloisonné, others as champlevé, and others as a combination. Certainly, the 20th century peacock brooch from Portugal displays characteristics of both. The tips of the tail feathers are champlevé, whereas the body is clearly cloisonné. At the upper left is a late 19th century gilt and intricately enameled box from France. The piece at the bottom is an elaborate, two-piece belt buckle that would have been worn on a cloth sash. The translucency of the brightly colored enamel and delicate swirls are nothing short of dazzling.

A combination of Cloisonné and champlevé can be found in a single piece. These pieces open the door to interesting discussions as to whether a piece is cloisonné or champlevé. These are examples of pieces some would identify as Cloisonné, others as champlevé, and others as a combination. Certainly, the 20th century peacock brooch from Portugal displays characteristics of both. The tips of the tail feathers are champlevé, whereas the body is clearly cloisonné. At the upper left is a late 19th century gilt and intricately enameled box from France. The piece at the bottom is an elaborate, two-piece belt buckle that would have been worn on a cloth sash. The translucency of the brightly colored enamel and delicate swirls are nothing short of dazzling.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

Cloisonné, by its very name, describes a process whereby thin strips of flattened metal are used to form the walls of cells (picture a honeycomb) that are then filled with different color enamels to form a pattern, design or image. There is, however, a type of wireless cloisonné that was perfected in Japan by the Ando Cloisonné Company (Ando Shipo-yaki) during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This cloisonné is produced in the traditional manner, but the wires (or cells) are removed prior to firing, which results in a smooth surface uninterrupted by separations. This wireless cloisonné is a type of Shipoyaki cloisonné known as Musen shippo. In fact, Ando created at least 12 different types of cloisonné that are worth researching.

At the left is a 9-inch tall bronze lamp decorated overall in brightly colored enamel in a floral motif. The enamels are in blue, yellow, red, green, turquoise and white. The lamp was made in Leipzig, Germany by HASAG (Hugo Schneider), a company that began making lamps in 1863. The detail of the bowl of a 1920s Egyptian revival spoon, right, displays the high quality and fine detail than was achieved in the use of enamels. The absence of damage attests to the durability of enamel on this 150-year-old lamp and nearly 100-year-old spoon.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

Everything from large lamps to small spoons could be decorated with enamel. At the right is a 9-inch tall, bronze lamp decorated overall in brightly colored enamel in a floral motif. The enamels are in blue, yellow, red, green, turquoise and white. The lamp was made in Leipzig, Germany by HASAG (Hugo Schneider), a company that began making lamps in 1863. The detail of the bowl of a 1920s Egyptian revival spoon, far right, displays the high quality and fine detail than was achieved in the use of enamels. The absence of damage attests to the durability of enamel on this 150-year-old lamp and nearly 100-year-old spoon.

Niello

Niello is a black metallic composite of sulfur with silver, copper or lead used to fill incised designs in metal, usually silver. A molten alloy of silver, lead and copper is mixed with sulfur resulting in a black compound that is dried then made into a powdered form. This powder is spread on the surface of a metal that has been engraved with a design and treated with a flux such as ammonium chloride or borax. The surface is then heated, causing the powder to melt and run into the engraved channels. The surface is then scraped and polished leaving only the incised areas filled with the black niello. Silver is typically used as the base metal for the startling contrast between the bright silver and dark black pattern.

The name “niello” is derived from the Latin word for the color black, “nigellum,” which, during medieval-era Latin, became “nigello” then “neelo.” In his book, The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt, W. Stephenson Smith identifies the earliest examples of niello as originating in Syria around 1800 B.C. The artisan of Egypt perfected the use of niello, an art that quickly spread to Rome and Greece. By the 8th century, the art of niello had spread throughout Europe as evidenced by the famous Tassilo Chalice at the Kremsmünster Abbey in Austria, the 9th century Strickland Brooch, Fuller Brooch and ring of King Æthelwulf of Wessex (839-58), all of which are in the collection held by The British Museum.

The type of niello most people in the antiques trade recognize is jewelry produced in Siam. Siam officially became “Thailand” in 1939; in 1945, it again became “Siam” and then back to “Thailand” in 1949. This image shows a pair of earrings and a panel from a bracelet marked “Siam” – pieces adorned with niello are known as “nielli.” Niello made in Siam is unique in that niello is absent in the engraved areas, contrary to most nielli. In Siam, the pieces are re-engraved after heating, thus exposing the silver beneath. Gold is also used as the background material, although silver is the preferred metal for the jewelry of “Siam.”

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

The art of niello peaked during the Renaissance when this decorative element was used on everyday objects such as goblets, knife handles, jewelry, plaques, icons and boxes. Today, items decorated with niello are still produced in the Balkans, India and in Russia where it is known as Tula work, after the city of Tula that began making nielli during the 18th century.

Guilloché

Guilloché is a precise engraving technique in which a complex, elaborate, repetitive, interlocking, wavy design is mechanically incised into a durable material such as metal or stone by what is known as “engine turning” by using a special lathe called a rose engine lathe. Guilloché designs can be applied to paper and are often used on currency; however, on paper, it is applied from an engraved plate, much like any engraving on paper.

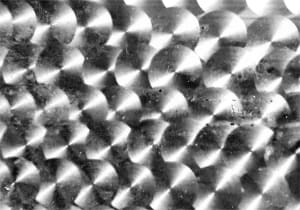

This is an image of Guilloché engraving on the inner surface of a vintage 1930, sterling silver cigarette case.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

When I was a kid, I had a geometric drawing machine called a Spirograph, which will exemplify the idea of engine turning to many who remember that game. With the use of a pencil and movable templates, you could draw highly detailed roulettes. The game was based on the rose engine lathe, which could engrave these curves and roulettes on metal or stone. Guilloché can be readily found on the interior of many vintage cigarette cases, watch faces and watch cases.

Guilloché enameling, which has been practiced since the 17th century, is simply the application of a translucent, brightly colored enamel over an engine-turned design. Guilloché enameling can be found on watch cases, goblets, jewelry, snuff boxes, compacts and the barrels of fine pens like the Graf von Faber-Castell. Another feature, often seen on jewelry, especially brooches, is the application of painted highlights on Guilloché enameling.

The guilloché engraving can be readily seen beneath the translucent enamel on these items: sterling silver thimble with floral overpainting, 14kt gold ladies watch in royal blue, lady’s watch in red with gilt fleur de lis, and an Albert Scharning enamel brooch depicting a sailboat during sunrise. Note how the guilloché engraving mimics the rays of the sun and waves in the water.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

Guilloché enameling became extraordinarily popular during the last quarter of the 19th century and rapidly replaced taille d’epargne (discussed later) as a favorite decorative element for jewelry.

Plique-à-jour

Plique-à-jour is an enameling technique that shares some characteristics with Cloisonné in that transparent, translucent and even opaque vitreous enamel is used to fill cloisons or cells (imagine a honey-comb of different shapes). The cells in plique-à-jour, however, do not have a metal backing in the finished product. This method allows light to pass through the enamel, which gives it a vibrant, illuminated, stained-glass window effect. The temporary mica or copper backing that is initially used to keep the enamel within the cell is removed when the item is finished. Smaller cells require no backing during production as they rely on surface tension to maintain the integrity of the enamel within the borders of the cell. The process is difficult and achieved only by the most experienced artisans. A single piece of jewelry, usually executed in gold, can take months to complete.

These two ethereal examples of plique-à-jour are classic in their delicate appearance and expert craftsmanship. The enamel on the brooch and pendant is set in 18kt gold.

Courtesy of Nancy Schuring of Devon Fine Jewelry

There is a great deal of controversy over the literal translation of the term “plique-à-jour.” The literal translation “letting in daylight” is “laisser entrer la lumière du jour.” “Plique” is translated as “applied,” while “a jour” means “up to date.” The term “de plique-à-jour” was first recorded during the 14th century and it is possible that in the Old French, the meaning was more logical. The meaning of the word “plique” varies, depending on how it is used. Despite the controversy, the “letting in daylight” has become the accepted meaning.

The origins of plique-à-jour are not exact, but the method most likely originated during the 6th century in the Byzantine Empire. There is no doubt that method was vastly improved during the 14th century by Benvenuto Cellini, a full account of which can be found in the Dictionary of Enamelling: History and Techniques by Erika Speel.

Plique-à-jour, which is still being produced, had a great resurgence during the Art Nouveau era during which some of the most remarkable examples of plique-à-jour were produced.

Gripoix

Gripoix is another technique developed during the 19th century and is attributed to Augustine Gripoix. This technique is derived from pâte de verre, which, literally translated, is “dough” or “paste of glass” (think of the consistency of liver pâte). The most widely accepted translation, however, is “molten glass” (in which case “fondue de verre” makes more sense). Pâte de verre is actually molded glass rather than the poured glass seen in Gripoix. I would enjoy hearing from our French-speaking readers with their opinions about these terms.

Gripoix is made when molten glass is poured into a mold, framework or a bezel setting and the individual pieces are left to harden and later polished and assembled to make a necklace or brooch or any quality piece of jewelry. Gripoix, unlike enameled pieces that utilize binding agents, is not kiln fired. All genuine Gripoix is made by hand rather than the machine-made glass beads seen in mass produced costume jewelry. The distinction between Gripoix and enameling is the

Gripoix is found in fine vintage jewelry by designers such as Chanel, Dior, Givenchy, Lanvin, Piguet, Balenciaga, Christian Lacroix, Charles Worth and others. Not all pieces made by these designers contain Gripoix so it is important to become familiar with the look of genuine Gripoix. Currently, Augustine Paris, operated by Thierry Gripoix, produces the highest quality Gripoix available today.

This appearance of this textured gold brooch with a hardstone cameo is greatly enhanced by the black enamel tracery seen in many mid-Victorian pieces of jewelry.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

Taille d’epargne

Taille d’epargne is, simply put, a decorative element of black enamel tracery utilized in decorating jewelry (usually gold) or fine objects such as boxes, tumblers and other small objets d’art. The term “taille d’épargne”, translated as “saving cut,” is derived from the French verb, “tailler,” which means to cut, carve, whittle, engrave, hew or hack. Taille d’epargne is very like champlevé in that a cut area is filled with enamel; however, the areas filled with enamel in taille d’epargne are small, typically fine, thin lines and unlike champlevé where many bright color enamels are used, the enamel in taille d’epargne is opaque rather than translucent and usually black; blue is also used to a lesser degree.

Taille d’epargne was extremely popular during the mid-19th century and was especially used in gold jewelry, often bloomed or burnished gold, to enhance the contrast between the light metal and darker enameling patterns.

These taille d’epargne brooches are from the second quarter of the 19th century. Note the pin visible from the front of the pieces; a sure clue to early-19th century pieces.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

This is an unusual set of taille d’epargne in blue enamel. The brooch and matching earrings date from the mid-nineteenth century. The set is finely crafted with textured gold in a style reminiscent of Etruscan pieces with which the Victorians were enamored.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

Basse-Taille

Basse-Taille, which can be traced to 13th century Italy, is an enameling technique in which colorful, translucent enamels are used to fill-in low relief patterns on metal, usually gold or silver. Unlike champlevé or taille d’epargne in which the surface of the enamel is even with the surface of the surrounding metal, the enameling in basse-taille is lower than the surrounding framework; it is also not applied as heavily and so is more translucent. Silver, gold, copper or various minerals are added to the glass to impart vibrant colors. Basse-Taille means “low cut” and refers to the enamel-filled, relief-work in the base metal, which is usually silver or gold.

Basse-Taille means “low cut” and refers to the enamel-filled, relief-work in the base metal, which is usually silver or gold as in this 18kt gold, Basse-Taille brooch.

Courtesy of Nancy Schuring of Devon Fine Jewelers

In creating a piece of Basse-Taille, the artist begins with a tool known as a tracer. The tracer is used to outline the design on the gold base. Once the outline of the design is made, the design within the outline is created by using a variety of chasing tools including: liners, undercutting tools, running punches, matting tools, stamps, and planishing tools. These tools are used to make recesses of varied depth in the base metal into which the enamel is placed before the piece is fired. Different depth wells will impart variations in color and intensity for the same enamel; shallow wells result in a more translucent, lighter appearance whereas deeper wells result in a darker opalescent, or even opaque appearance. The base of the cut-out areas is often hand-stamped or engraved with designs that can be seen through transparent or opalescent enamels, not unlike the process used in Guilloché.

Vitreous Enamel

Vitreous Enamel, commonly known as porcelain or porcelain enamel is produced when finely-ground glass is fused to a metal with the use of heat. When heated, the powdered glass melts into a liquid that coats a metal substrate and eventually hardens as it cools. The word “vitreous” is a derivative of the Latin word “vitreum,” which, literally translated, means “the glass.” The metals used as a base for enameling are stainless steel, cast iron, aluminum, gold, silver or copper. Once the powdered glass is melted and cooled it forms a very hard, durable surface that resists the effects of temperature and many chemicals; it may, however, shatter or chip when the underlying metal is exposed to undue stress such as bending or after being dropped on a hard surface.

Perhaps the most widely recognized item of vitreous porcelain to which most people have been exposed (literally and figuratively) is the enamel cast iron bathtub. Most people use items made of vitreous enamel every day, these include: saucepans, watch faces, cooking ware, washing machine drums, street signs and vintage subway station signs; porcelain enameled steel was also used for buildings such as the post-WWII Carl Strandlund Lustron Houses. As testament to the durability of vitreous enamel, The Daily Mail, July 1, 2011, published photographs of Captain Edward Smith’s vitreous enamel, cast-iron bathtub still intact amid the ruins of the Titanic after almost 100 years, 12,500 feet below the frigid salt waters of the North Atlantic Ocean.

The cup pictured here is an example of the beauty and artistic achievements that can be obtained with the use of vitreous enamel. This beaker was made for the coronation of Tsar Nicholas II and Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna in 1896. One side of the cup displays highly detailed interlacing patterns and braiding with a central cartouche encircling the cyphers of Nicholas and Alexandra with the date of “1896.” The opposite side of the cup illustrates the Romanov eagle. It was meant to be known as the Coronation Cup, but as a result of its tragic history, it is more commonly known as the Khodynka Cup of Sorrows, the Sorrow Cup or the Blood Cup. During the coronation celebration on May 18, 1896, gifts, including this beaker, were distributed to the crowd of more than 500,000 gathered at Khodynka Field when a rumor spread that each of the cups contained a gold coin. The crowd surged forward and in the ensuing stampede, more than 1,000 people were trampled to death. The Tsarina henceforward referred to the souvenir as “the cup of sorrows.” The rim of this cup is chipped in two places, which shows the underlying copper. My sister has a collection of these beakers and almost each one has similar damage, which may simply be the result of 123 years of existence, although one can’t help but wonder if the damage is the result of the tragic circumstances of the day.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

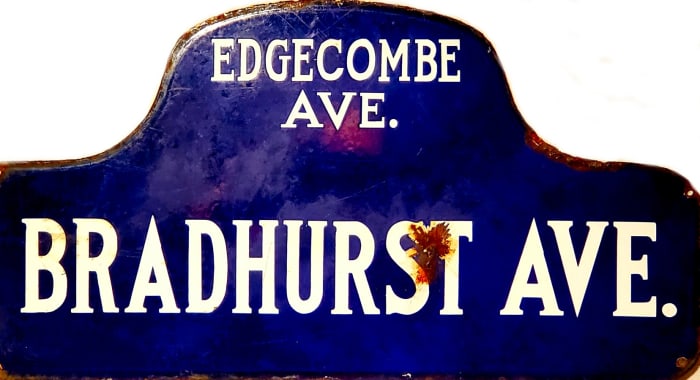

Vitreous enamel is probably the most commonly encountered type of enamel. It would be difficult to find a home today that does not contain enamel in one form or another. Because of its durability and resistance to temperature extremes, vitreous enamel has been used for more than a hundred years on street and underground signs.

Street signs, like this New York City humpback street sign from the 1910s, played an important role before the days of Global Positioning Technology and OnStar. These humpback street signs were used in NYC from the 1910s through the 1950s and were a favorite target for rock-hurling kids as can be seen by the stress fracture on the “ST” of “Bradhurst.” This sign is in remarkable condition after fifty years or more in the hot sun and freezing rain.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

This nineteenth century, hand-painted, enamel, Austrian, silver and gilt ship on wheels was made strictly for ornamentation.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

The most desirable enamel items were made in Austria and Russia. Hermann Boehm of Austria is perhaps one of the most talented artists to produce such objets d’art. Plaques, miniature furniture, boxes, and opera glasses were some of the many stunning enamel pieces made for decoration or use. The exquisite detail in these miniature enamel objects can only be achieved by superior artistry and creativity.

For hundreds of years, colorful enameling was used to decorate many types of pins and medals such as awards, anniversary pins, lapel pins, stick pins and even buttons. During the thirteenth century, lapel and stick pins first appeared in China; they have been used ever since. Enamel lapel and stick pins have been used by the military as company insignia, by politicians during campaigning and to identify members of many different organizations.

This multicolored, religious, years-of-service enamel pin celebrated thirteen years of service with a new bar being added for each year of service. The “Century Journal Course” cycling medal from June 16th 1900 is decorated with blue and red enamel that has remained almost pristine for 120 years.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

Meenakari

Meenakari is another type of enameling that began in Persia and spread throughout Asia into India where the art was perfected, and is still practiced today. Meenakari is a very colorful, bright enameling applied to metals such as gold, silver and copper that is then kiln-fired, causing the enamels to harden and fuse with the base metal. The process is much like that used in Champlevé, where the surface of the metal is engraved with a design and filled with colorful enamels prior to heat fixing. Once cooled, the piece is cleaned and polished with a mixture of lime and tamarind, which enhances the luster.

The enamel colors in Meenakari are derived from the use of a mixture of metal oxides and powdered glass that attains its true color upon firing. The colors appear best on gold then silver and finally copper. Today, the base metal used most in Meenakari is white metal. There are three different types of Meenakari defined by the specific colors used, the number of colors used: Ek Rang Khula Meena uses only a single transparent color, Panch Rangi Meena uses five colors including red, white, green, light blue and dark blue, and Gulabi Meena in which pink is the primary color.

Enameling has long been used as a decorative element on glass and porcelain. The technique for enameling glass and porcelain is very similar to enameling on metals with the use of glass painting powders and some variations in temperature; stencils may also be used. When fusing enamels to glass, the glass is placed in a room-temperature kiln. The heat is slowly raised, then lowered and maintained to fuse the enamels to the surface then slowly reduced until room temperature. This slow increase and decrease in heat help to stabilize and reduce stress on the glass. Enamel may be used to highlight specific areas on porcelain and glass or used to decorate a piece overall.

This 14-inch, hand-painted, “R St. K” Amphora, Turn-Teplitz, Austrian vase is decorated overall in polychrome enamels applied to the surface. The enamels add depth and luster to hand-painting on porcelain.

Courtesy of Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

Enameling has succeeded as an art for thousands of years, an art that remains admired and practiced today by artisans and manufacturers in almost every culture. What better testament to any art form than such an enduring legacy? Neither time nor the elements can fade the beauty of expertly crafted enamels.

As I always suggest, go out, explore, touch, examine, ask questions and soon the difference between different types of enamel will become immediately apparent and champlevé will never be cloisonné again.

You May Also Like:

The Key to Identifying Satsuma