“Oh, sometimes I do better than others.”

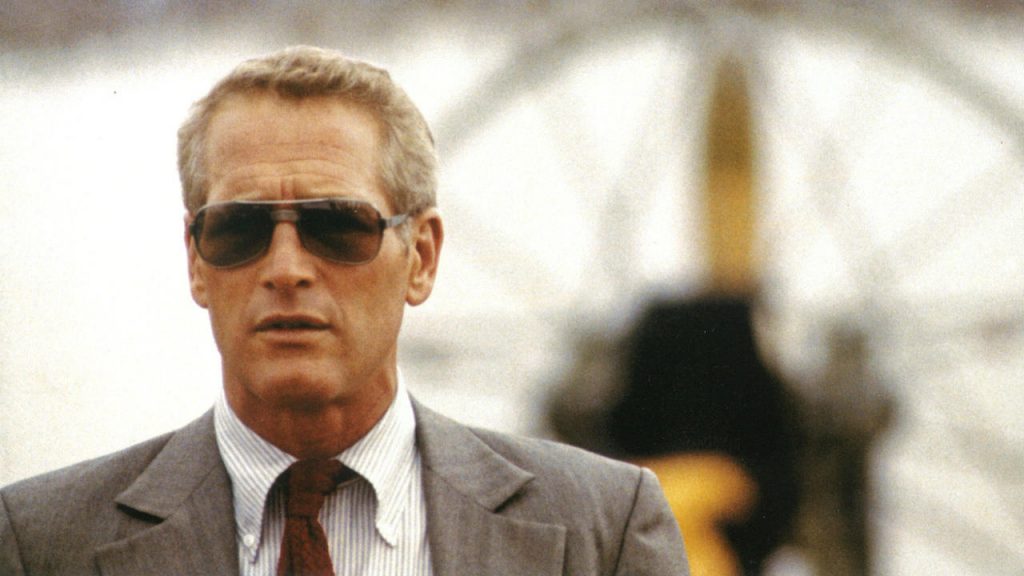

Paul Newman is the movie star par excellence. Some might have been more iconic or quotable, but no actor has managed to rival Newman’s flawless blend of good looks, talent and longevity. He emerged from the mold of classic Hollywood in the 1950s and yet helped break the mold of the New Hollywood movement in the 1970s. He’s been nominated for an Oscar in five different decades, including three nominations (and one win) after In 1985 he received a Lifetime Achievement Award!

This is all worth noting because Newman’s greatest single talent, more than good looks or longevity, was his adaptability. The actor never went down for long because he could always tell when he needed to change the characters he played or the filmmakers he worked with. As a result, these incursions can be difficult to detect. They were often introduced and corrected over the course of a single film, and the film that best illustrates this is the 1975 film The drowning pool.

The film, based on the Ross Macdonald novel of the same name, is a Newman outlier for a number of reasons. It was the only sequel he appeared in during his lifetime, and it marked a pivotal mid-career transition moment. The end result is less horrifying than chaotic and incongruous with what the story is trying to accomplish.

The film’s origins are tangled like the scripted mystery. Newman had achieved great success with the first part of the series, harpers (1966), in which he appeared as the heir apparent of Humphrey Bogart The Big Sleep (1946). harpersWilliam Goldman’s screenwriter was quick to write a sequel, but Newman’s busy schedule was prioritized and the franchise was shelved. The character of Harper (changed from Archer in the novels) was revived in 1973 when Walter Hill was hired to direct an adaptation of The drowning pool.

Originally, the Harper role was to be recast, and Hill, a rising talent, was slated to shed the original film’s stupidity for a tougher approach. It was the age of dirty harry, and the plan was to put “a little more muscle” behind the private investigator. Producers were eventually put off by the new direction and Hill left, but the sting of his departure was soured by the fact that Newman agreed to reprise his role. Newman’s return raised the film’s profile, and Lorenzo Semple Jr. was brought in to rewrite Hill’s screenplay.

Semple was an accomplished wordsmith himself, with credits like the classic thrillers The parallax view (1974) and Three Days of the Condor (1975). He changed the novel’s setting from California to Louisiana to emphasize the film, and at one point considered changing the Newman character’s name to Dave Ryan. The latter proposal was rejected, albeit only a few weeks before production. The overarching narrative is that everyone was keen to stand out from the film harperswhich is ironic considering how similar the two films are when viewed together.

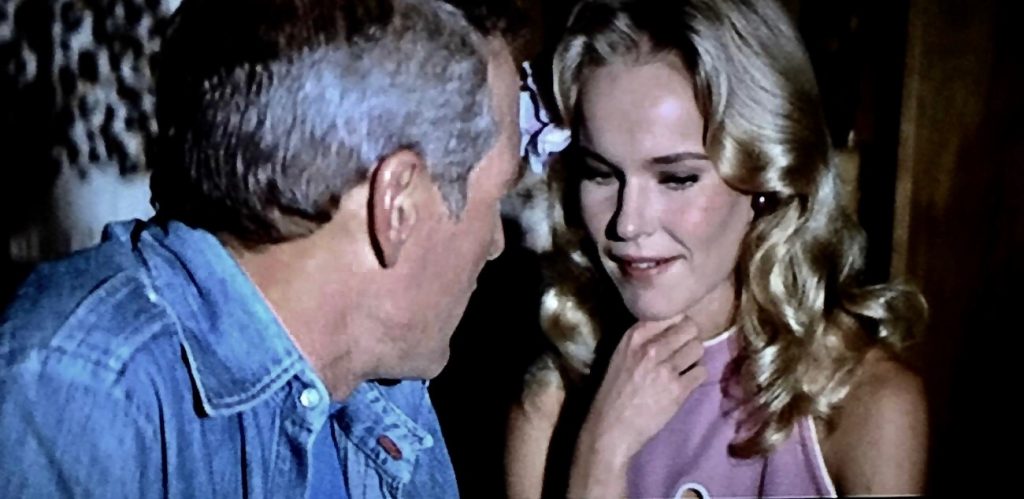

The drowning pool has an almost identical plot to the first film, in which Harper is drawn into the tangled web of a wealthy family. There’s another aging matriarch (Joanne Woodward), another feisty daughter (Melanie Griffith), and another suspicious man (Anthony Franciosa) who may or may not be meddling in the family’s criminal activities. All of the story beats involving the characters play out as they did harpers, except for the matriarchal character; which forms a deeper bond with the detective than its predecessor.

The chemistry between Newman and Woodward shouldn’t surprise fans who’ve seen them together, and stands out as one of the film’s subtle highlights. Her dynamic has a weathered quality compared to other detective-client relationships, and while largely unspoken, it caves The drowning pool a lost quality that was perfect for the Watergate era.

The other standout component of the film is Newman’s performance. The actor is repeatedly teased for being too old in the film, and the moments where he confronts (and taunts) his age quietly introduce a new trope in noir storytelling. There have been dozens of detectives over the hill since then, but Harper, with his graying hair and grizzled gait, was the first of his kind (Robert Mitchums Sr. stated Farewell, my beauty came a month later).

These sonic innovations are what make the script so frustrating. There are traces of Hill’s original draft in the scenes involving henchmen from Louisiana and the main set piece (which involves a literal drowning pool), but they clash with Semple’s intimate explanatory conversations. Both writers have a clear vision for the story that they would perfect in later films, but here, fused with no sense of harmony, they sabotage each other. Harper is too vulnerable to be an action hero but too deadly to be an aging detective. He feels separated from the man he was ten years ago.

The frustration only mounts when you look at the source material. Ross Macdonald began as an impersonator of Raymond Chandler, mimicking his idol’s wording and tone to develop his own style. The moving target (Basis for harpers) and The drowning pool were Macdonald’s first two novels and therefore the most derivative. If you look at later efforts like black money or the cold, but it is clear that the author has distinguished himself as a master. Packed with aphorisms and inventive structures, these novels would have made for more thoughtful sequels if Warner Bros. had adapted them instead.

Stuart Rosenberg’s direction doesn’t help much against the structural flaws. Rosenberg had proven himself to be a capable hand with Newman vehicles Cool hand Luke (1967) and pocket money (1972), but he had been through rough times and was reportedly “desperate” for the gig. Sources later claimed director Jack Garfein was in demand for the film before Newman made the push for his longtime friend.

Rosenberg manages to evoke the allure of his Louisiana setting, and the decision to filter most scenes through a muted green color palette actually proved influential on the neon-noir wave that followed (led, appropriately, by Hill’s). The driver). The biggest blow to Rosenberg here is that he doesn’t build any real tension.

The predictable beats become all the more predictable as the director assembles them as simply as possible. Compared to something like Cool hand Luke, which prioritizes character, one has to wonder if Rosenberg’s commitment to plot has stifled his eye for presentation. It delivers a hollow, albeit handsome, product.

The drowning pool hardly made a splash when it was released. Critics’ reaction was muted, and box office returns weren’t much better. Newman took the elements of the film that worked (the aging, the reflection) and, without missing a beat, switched to older roles slapshot (1977), Fort Apache, the Bronx (1981) and The judgment (1982). The drowning pool is little more than a footnote today, but it remains an intriguing linchpin between Newman the superstar and Newman the elder statesman.

TRIVIA: Newman, Woodward and Francoisa had previously appeared together in The long, hot summer (1958).

…..

-Danilo Castro for Classic Movie Hub

All articles from Danilo’s Film Noir Review can be found here.

Danilo Castro is a Film Noir fan and contributing writer for Classic Movie Hub. You can read more articles and reviews by Danilo at the Film Noir Archive or follow Danilo on Twitter @DaniloSCastro.