Edmonia Lewis had many odds against her and she beat every one to shatter expectations about what women and minority artists could accomplish.

Edmonia Lewis, albumen print, c.1870.

Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Lewis was the first woman of African-American and Native American heritage to achieve international recognition and fame as a sculptor in the fine arts world. Her work is known for incorporating themes relating to black people and indigenous peoples of the Americas into Neoclassical-style sculpture.

Some of Lewis’ life is still a mystery, so it’s not known exactly when she was born, but it’s commonly believed have been in Ohio or New York between 1843-1845. Her father was a free African-American and her mother a Chippewa (Ojibwa) Indian and she was given the name Wildfire. Orphaned before she was five, Lewis lived with her mother’s nomadic tribe until she was twelve years old and her life revolved around swimming, fishing and making and selling crafts.

Her older brother, Sunrise, left the Chippewas and moved to California where he became a gold miner. He financed his sister’s early schooling in Albany, N.Y., and also helped her to attend Oberlin College in Ohio in 1859. Oberlin was one of the first schools to accept female and black students. While at Oberlin, she shed Wildfire and took the name Mary Edmonia Lewis.

She developed an interest in the fine arts, but her time at Oberlin ended abruptly when she was accused of poisoning two of her white roommates. Lewis was acquitted of the charge, but she had to endure a highly publicized trial and also a severe beating by white vigilantes, who had left her for dead. She was also accused of stealing art supplies and not permitted to graduate from Oberlin.

Lewis left Oberlin in 1863 and, again through her brother’s encouragement and financial assistance, moved to Boston. There she met the portrait sculptor Edward Brackett, under whose guidance she began her limited sculptural studies. With a minimum of training and experience, Lewis began creating medallion portraits of well-known abolitionists including William Lloyd Garrison, Charles Sumner, and Wendell Phillips. With sales of her portrait busts of abolitionist John Brown and Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the Boston hero and white leader of the celebrated all-African-American 54th Regiment of the Civil War, Lewis was able to finance her first trip to Europe in 1865.

After traveling to London, Paris, and Florence, Lewis decided to settle in Rome and rented a studio near the Piazza Barberini during the winter of 1865 and 1866. She quickly learned Italian and became acquainted with two prominent white Americans also living in Rome — actress Charlotte Cushman and the sculptor Harriet Hosmer. A number of American sculptors lived in Rome at the time because of the availability of fine white marble and the many Italian stone carvers who were adept at transferring a sculptor’s plaster models into finished marble products. The Neoclassical style that was marked by a lofty idealism and Greco-Roman resources was the favored style at this time.

Lewis was unique among sculptors of her generation in Rome, as she did most of her work herself and rarely hired Italian workmen.

Although she had not been able to take human anatomy classes at Oberlin because they were limited to white male students, Lewis’ sculptures were still impressive enough to earn her international acclaim. Her subjects included Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Horace Greeley, and one of her patrons was President Ulysses S. Grant. Her work challenged the norms of the overwhelmingly white and male art world decades before the scene started to open up to different types of artists.

Lewis’ multiracial identity and gender were formative in her selection of subjects. Between 1866 and 1872, she completed a series of marble sculptures on the popular theme of Hiawatha (shown here) and Minnehaha (shown below), drawn from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem, “The Song of Hiawatha” (1855). These cabinet-sized busts represent the star-crossed lovers from once-warring nations and blend an idealized treatment of form with Native American dress and accessories.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art/public domain

Lewis greatly admired Longfellow’s poetry, especially his epic poem, The Song of Hiawatha. The poem inspired at least three sculptures: “The Wooing of Hiawatha,” “The Marriage of Hiawatha and Minnehaha,” and “The Departure of Hiawatha and Minnehaha.”

While in Rome in 1869, Longfellow visited Lewis’ studio. He sat for a portrait and probably saw the sculptures his poem inspired. The only surviving known work from her Hiawatha and Minnehaha series was believed to be a pair of small busts of the young lovers, but in 1991, Lewis’ “Marriage of Hiawatha and Minnehaha” was rediscovered.

According to the Smithsoian American Art Museum, Lewis often created sculptures of Native Americans, and possibly chose the character of Hiawatha because he had the same Ojibwa heritage as her mother. The coming together of the Ojibwa and Dakota tribes may refer to Lewis’ hopes for reconciliation between the North and South after the Civil War. In the story, Hiawatha later marries Minnehaha with the wish that “… old feuds might be forgotten/And old wounds be healed forever.”

While living in Rome, Lewis created “The Death of Cleopatra,” her largest and most powerful work. Cleopatra was a common subject at the time, but unlike her contemporaries who often depicted Cleopatra only contemplating suicide, Lewis showed the queen’s death more realistically, after the asp’s venom had taken hold — an attribute some viewed as “ghastly.”

Despite that prevailing attitude toward the sculpture, Lewis forged ahead and poured more than four years of her life into it. In 1876, she shipped the almost 3,000-pound sculpture to Philadelphia so that it could be considered by the committee selecting works for the Centennial Exhibition. Lewis had feared that the judges would reject her work, but the piece earned great acclaim and critics raved that it was the most impressive American sculpture in the show.

“Some people were blown away by it. They thought it was a masterful marble sculpture,” said Karen Lemmey, art historian and curator of sculpture at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The sculpture now resides at the museum and greets visitors who climb to the third floor in the Luce Foundation Center.

“The Death of Cleopatra,” carved 1876, marble, 63” x 31-1/4” x 46”, now in the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The legendary queen of Egypt is often best known for her dramatic suicide, allegedly from the fatal bite of a poisonous snake. Here, Lewis portrayed Cleopatra in the moment after her death, wearing her royal attire, in majestic repose on a throne. The identical sphinx heads flanking the throne represent the twins she bore with Roman general Marc Antony.

Courtesy of Smithsonian American Art Museum/public domain

“Lewis shattered expectations about what female and minority artists could accomplish,” Lemmey said. “It was very much a man’s world. Lewis really broke through every obstacle, and there’s still remarkably little known about her … It’s only recently that the place and year of her death have come to light — 1907 London.”

The Cleopatra sculpture has quite a history itself. Not long after its debut, it was presumed lost for almost a century, but made various appearances including at a Chicago saloon, marking a horse’s grave at a suburban racetrack, and eventually reappearing at a salvage yard in the 1980s. The Smithsonian Museum has an online exhibit that documents the statue’s storied history and conservation.

Lewis proved to be particularly savvy about winning over supporters in the press and in the art world by altering her life story to suit her audience.

“Everything that we know about her really must be taken with a grain of salt, a pretty hefty grain of salt, because in her own time, she was a master of her own biography,” said Lemmey.

Lewis changed her personal history to win support, but she did not welcome reactions of pity or condescension.

“Some praise me because I am a colored girl, and I don’t want that kind of praise,” she said. “I had rather you would point out my defects, for that will teach me something.”

Most of Lewis’ sculptures have unfortunately not survived. Although portrait busts of abolitionists and patrons such as Anna Quincy Waterston, and subjects depicting her dual African-American and Native American ancestry were her specialty, Lewis also completed several mythological subjects or “fancy pieces” such as “Asleep,” “Awake,” and “Poor Cupid.” She also created at least three religious subjects, including a lost “Adoration of the Magi” of 1883, and copies of Italian Renaissance sculpture.

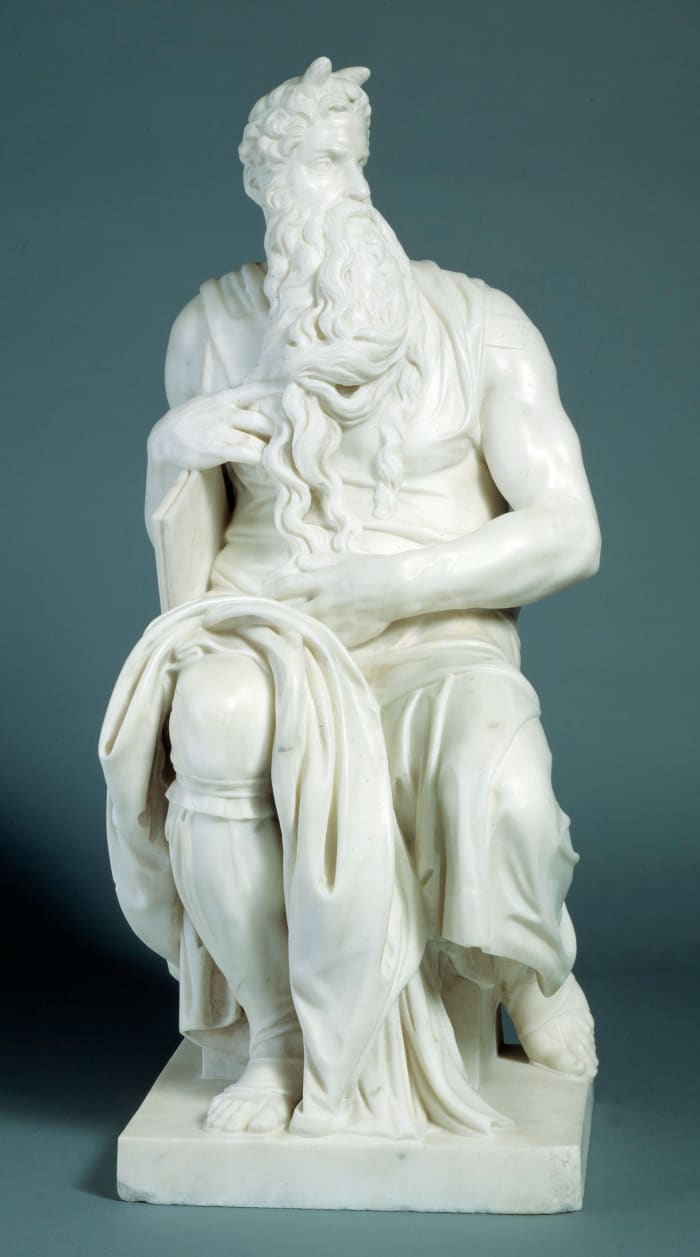

According to The Smithsonian, her “Moses,” copied after Michelangelo, is an example of Lewis’ imitative talents; the sensitively carved “Hagar” (also known as “Hagar in the Wilderness”) is considered a masterpiece among her known surviving works. In the Old Testament, Hagar — Egyptian maidservant to Abraham’s wife, Sarah — was the mother of Abraham’s first son Ishmael. The jealous Sarah cast Hagar into the wilderness after the birth of Sarah’s son Isaac. In Lewis’ sculpture, Egypt represents black Africa, and Hagar is a symbol of courage and the mother of a long line of African kings. That Lewis depicted ethnic and humanitarian subject matter greatly distinguished her from other Neoclassical sculptors.

Lewis’ “Moses (after Michelangelo),” 1875, marble. Lewis developed her skills in Rome by copying classical sculptures. These copies would often be sold to American tourists, providing a much-needed source of income. The original sculpture of Moses by Michelangelo, completed around 1515, stands in the tomb of Pope Julius II in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. To a black female sculptor, the opportunity to emulate such an exalted artist’s work must have meant a great deal. The figure of Moses himself may also have been an inspiration. By rescuing the Israelites from Egypt, Moses exemplified the desire for freedom felt by many blacks during the nineteenth century.

Photo courtesy of Smithsonian American Art Museum/public domain

According to newspaper accounts, Lewis returned to the United States in 1872 to attend an exhibition of her works at the San Francisco Art Association, and again in 1875 to attend a concert in St. Paul, Minnesota. After 1875, facts concerning the remainder of Lewis’ life are a bit conflicting.

Lewis reportedly never married and had no known children. She lived in the Hammersmith area of London, England, before her death on September 17, 1907, in the Hammersmith Borough Infirmary. According to her death certificate, the cause of her death was chronic Bright’s disease. She is buried in St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Cemetery in London.

In addition to the Smithsonian, some of Lewis’ other pieces can be found at the Howard University Gallery of Art, Detroit Institute of Arts, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Baltimore Museum of Art.

She recently became the subject of a Google Doodle that pictures her working on “The Death of Cleopatra.” The New York Times also featured her on July 25, 2018 in its “Overlooked No More” series of obituaries written about women and minorities whose lives had been ignored by newspapers because of the cultural prejudice.

You might also like:

The Groundbreaking Leaps of Sculptor Augusta Savage

Pioneering Fashion Designer Ann Lowe

African American Art Sets Auction Records

Leonard Freed’s Photographs of Black Life Still Relevant Today