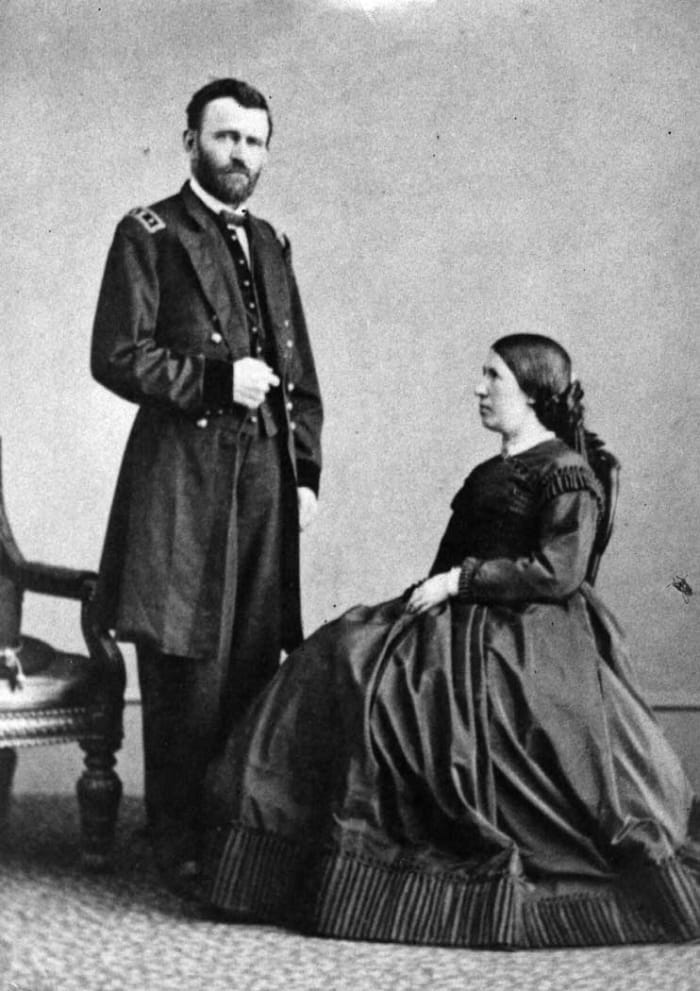

President Ulysses S. Grant and First Lady Julia Dent Grant occupied the White House from 1869 to 1877. As first lady, Julia Dent Grant was regarded as an unimpeachable White House hostess. During her role as first lady, Mrs. Grant planned weekly gatherings, afternoon teas and arranged many state dinners as well as serving as the driving force behind such public events as Independence Day and New Year’s Day celebrations.

The first lady had her work cut out for her in restoring the White House as the center of social society in Washington post Andrew Johnson’s impeachment trial, an event that closed the doors on any White House festivities.

President Ulysses S. Grant and First Lady Julia Dent Grant occupied the White House from 1869 to 1877.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Julia Boggs Dent was born on January 26, 1826, in St. Louis to Frederick and Ellen Wrenshall Dent. Coming from a highly social family, Julia learned skills that would later serve her well in the White House.

In 1869, the President and First Lady approached the Washington, D.C. merchant J.W. Boteler & Bro. to order china from Haviland & Co. in Limoges, France. In February 1870 the 587-piece service arrived at the White House. The total cost was $3,000. The dinner plate had a buff band framed by gold and black lines, overlaid with flowers in different colors and a version of the Great Seal of the United States in red and gold.

These French porcelain serving pieces, including a compote, a cake stand, and a dinner plate, were made by Haviland & Co. of Limoges, France, between 1869 and 1873. President Grant first ordered a state china service featuring this pattern in 1869, and reordered supplemental pieces in 1873 ahead of the White House wedding of his daughter, Nellie.

Courtesy White House Historical Association

Following a rather unfavorably executed White House dinner, Mrs. Grant discharged the chef and engaged the Italian steward, Valentino Melah for that now vacant position. Melah’s resume included the art of cookery practiced at fashionable hotels. His epicurean experience raised the food served at the White House to the highest level for its time. French cuisine often filled the plate settings at the dinner table. Mrs. Grant also loved Southern food and Melah often served her favorites.

It wasn’t unheard of to have 35 assorted dishes served at a White House dinner. But two hours was the fixed time for diners at the table. Following dinner invitees would then withdraw to the Red Room or Blue Room of the White House for conversation and cigars for the men before the curtain fell on the evening’s merriments.

During elegant banquets at the White House, the dining room and table were richly bedecked with floral arrangements and fruit. The china that adorned the table was the finest in Limoges china made by Haviland and Company. Each piece was beautified with a different hand-painted festoon of flowers, fruits or leaves. A highly unusual centerpiece was often featured on the table—a gift from the Mohawk tribe to the White House — a silver ship with a depiction of Hiawatha.

Each piece of the Grant White House China was decorated with a different hand-painted festoon of flowers, fruits or leaves. A hand-painted lily is showcased in the center of this 9-1/2” soup bowl. A label affixed to the back of the bowl reads: “This plate was in undefinedthe White House During undefinedPresident Grant’s Term of Office.” The bowl sold for $3,125.

Courtesy Heritage Auctions

In a vast deviation from the dark days of the Johnson administration, the White House organized receptions every Tuesday during the social season. Mrs. Grant was resolute that all those who wished to attend be permitted to do so. At these get-togethers, the upper-class women from the Washing, D.C., area would break bread with the White House servants.

To Mrs. Grant the image of the first lady should be as esteemed as the wives of foreign leaders. And she felt that her choice of the White House’s elaborate china settings went a long way toward that aspiration.

The two-year grand tour of Europe the Grants enjoyed influenced some of Julia’s china pattern selections. Following the tour Mrs. Grant chose what are described to as “fish plates,” which differ from but are meant to pair with the more traditional china patterns back home in the United States.

Having an affinity for Chinese porcelain, the Grants chose this beautiful 8-1/2″ undefinedfish plate while touring Europe. The Grants used the plate with earlier Chinese porcelain they had purchased.

Courtesy White House Historical Association

The Grants were a formidable team. While President Grant governed the country, it was the first lady who governed the White House. It was an arrangement that worked quite nicely for the couple. Through great personal challenges and hardships, the couple had earned their new roles together.

As a young, shy man, a then Lieutenant Grant lost his heart to friendly Julia. He made his love known, as he said himself years later, “in the most awkward manner imaginable.” She told her side of the story – her father opposed the match, saying, “the boy is too poor,” and she answered angrily that she was poor herself. The “poverty” on her part came from a slave-owner’s lack of ready cash.

Daughter of Frederick and Ellen Wrenshall Dent, Julia had grown up on a plantation near St. Louis in a typically Southern atmosphere. In memoirs prepared late in life – unpublished until 1975 – she pictured her girlhood as idyllic: “one long summer of sunshine, flowers, and smiles…” She attended the Misses Mauros’ boarding school in St. Louis for seven years among the daughters of other affluent parents. A social favorite in that circle, she met “Ulys” at her home, where her family welcomed him as a West Point classmate of her brother Frederick; soon she felt lonely without him, dreamed of him, and agreed to wear his West Point ring.

Notice the disparity in style between the scalloped botanical plates and what are affectionately referred to as fish plates. There’s a reason for that: President Grant and his wife toured Europe where they selected the unique Chinese pattern to pair with the more traditional china pattern back home.

Courtesy White House Historical Association

Julia and her handsome lieutenant became engaged in 1844, but the Mexican War deferred the wedding for four long years. Their marriage, often tried by adversity, met every test; they gave each other a life-long loyalty. Like other army wives, “dearest Julia” accompanied her husband to military posts, to pass uneventful days at distant garrisons. Then she returned to his parents’ home in 1852 when he was ordered to the West.

Ending that separation, Grant resigned his commission two years later. Farming and business ventures at St. Louis failed, and in 1860 he took his family–four children now–back to his home in Galena, Illinois. He was working in his father’s leather goods store when the Civil War called him to a soldier’s duty with his state’s volunteers. Throughout the war, Julia joined her husband near the scene of action whenever she could.

After so many years of hardship and stress, she rejoiced in his fame as a victorious general, and she entered the White House in 1869 to begin, in her words, “the happiest period” of her life. With Cabinet wives as her allies, she entertained extensively and lavishly. Contemporaries noted her finery, jewels and silks and laces. Upon leaving the White House in 1877, the Grants made a trip around the world that became a journey of triumphs. Julia proudly recalled details of hospitality and magnificent gifts they received.

President Grant’s rose medallion punch bowl, 6 1/2” tall and a diameter of 16”, from service of 360 pieces ordered in 1868. Used by the family in the White House. Sold for $12,075 in 2015.

Courtesy Cottone Auctions

After retiring from the Presidency, Grant became a partner in a financial firm, which went bankrupt. About that time he learned that he had cancer of the throat. He started writing his recollections to pay off his debts and provide for his family, racing against death to produce a memoir that ultimately earned nearly $450,000. Soon after completing the last page, in 1885, he died. Grant was 63.

The money from her husband’s memoirs, published by his friend, Mark Twain, along with her widow’s pension, allowed the former first lady to live in comfort, surrounded by her family, till her own death in 1902.

She had attended in 1897 the dedication of Grant’s monumental tomb in New York City where she was laid to rest. She ended her own chronicle of their years together with: “the light of his glorious fame still reaches out to me, falls upon me, and warms me.”

Excerpts used in this piece from WhiteHouse.gov are from The First Ladies of the United States of America, by Allida Black, copyright 2009 by the White House Historical Association.

You May Also Like:

How To Identify Antique Enamels