It was 1883, and the socially ambitious Mrs. William Kissam Vanderbilt (née Alva Erskine Smith) was determined to become part of New York’s high society and get on The List.

This was the famous list of “The Four Hundred” people who were New York’s high society of the Gilded Age. But to get on The List, Alva would need to go through the queen bee of New York’s social hierarchy, Mrs. Caroline Schermerhorn Astor, known as “The Mrs. Astor.”

Upholders of old money and tradition, Astor and Ward McAllister, the self-appointed “arbiter of social taste” and creator of the Four Hundred, were the gatekeepers of all things upper class. It was up to them to decide if your bloodlines were pure enough or last name was respectable enough to become one of the elites.

They decided that the Vanderbilt family was unacceptable for high society because they thought nouveau riche family patriarch, Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt, the ambitious entrepreneur who made his fortune in the railroad and shipping industry, was too crass and distasteful.

This did not sit well with Alva, who was married to Cornelius’ grandson, William Kissam Vanderbilt. She became determined to bring the Vanderbilts into what she thought was their rightful place in society and onto the list of the Four Hundred.

Her first step was hiring renowned American architect Richard Morris Hunt to build an extravagant French château-style mansion for her and William at 660 Fifth Avenue that overshadowed the opulent townhomes already lining the avenue. The super-sized estate was nicknamed “Petit Chateau.”

The home of Mr. and Mrs. Alva and William Kissam Vanderbilt, “Petit Chateau,” designed by renowned architect Richard Morris Hunt.

Courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Gallery

When Petit Chateau was done, Alva decided to have a housewarming party, but not just any housewarming. She wanted a party on a much grander scale, and on Monday, March 26, 1883, she hosted one of the most amazing parties that New York had ever seen.

Uniformed servants hand-delivered invitations, young socialites had practiced quadrilles (dances performed with four couples in a rectangular formation) for weeks, and, according to the New York Times, “Amid the rush and excitement of business, men have found their minds haunted by uncontrollable thoughts as to whether they should appear as Robert Le Diable, Cardinal Richelieu, Otho the Barbarian, or the Count of Monte Cristo, while the ladies have been driven to the verge of distraction in the effort to settle the comparative advantages of ancient, medieval, and modern costumes.”

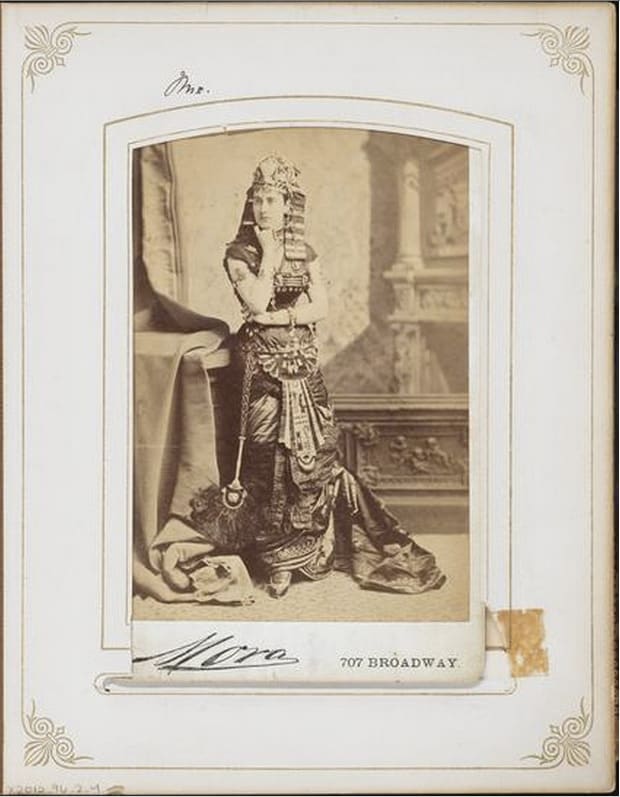

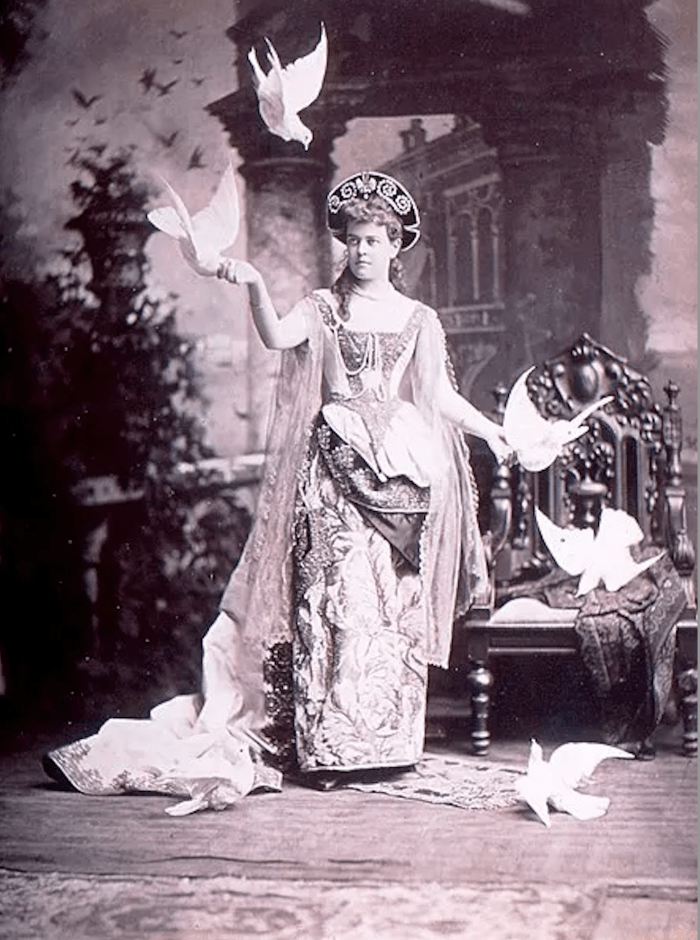

Alva Vanderbilt at her official opening of the chateau in March 1883, in her costume of a “Venetian Renaissance Lady.” The photographer apparently added the birds in later, for whatever reason.

Courtesy of PSNC Archives and Special Collections

With a mountain of wealth at her disposal, Alva spared no expense. She used every available resource, including the press, and invited journalists to take exclusive photographs of the decorations beforehand to help build hype. Alva also supposedly pulled one more trick from her sleeve: According to gossip, she used good old-fashioned manipulation to get on the Four Hundred and used Mrs. Astor’s daughter, Carrie, as a pawn. Like all young women of marrying age, Carrie had practiced a quadrille with her friends for weeks and anxiously awaited her invitation. When all her friends got theirs, and she still hadn’t, she asked her mother to find out why.

Alva claimed that since Mrs. Astor had never called on the Vanderbilt home on Fifth Avenue to introduce herself formally, she had no address to send an invitation to, so Mrs. Astor reluctantly visited Petit Chateau and left her visiting card. Their invitation was received the following day.

Some 1,200 New York socialites began arriving in carriages at the mansion at 10 p.m. as the fancy dress ball got underway. Police had to hold back crowds gathered to catch a glimpse of the society “it” men and women in their creative and over-the-top costumes. Mrs. Astor and Ward McAllister even attended.

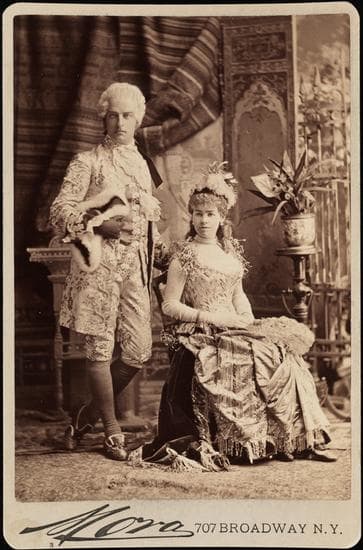

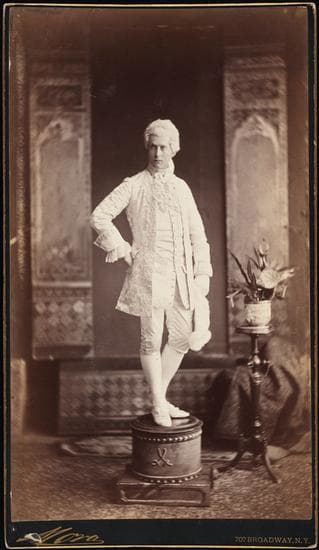

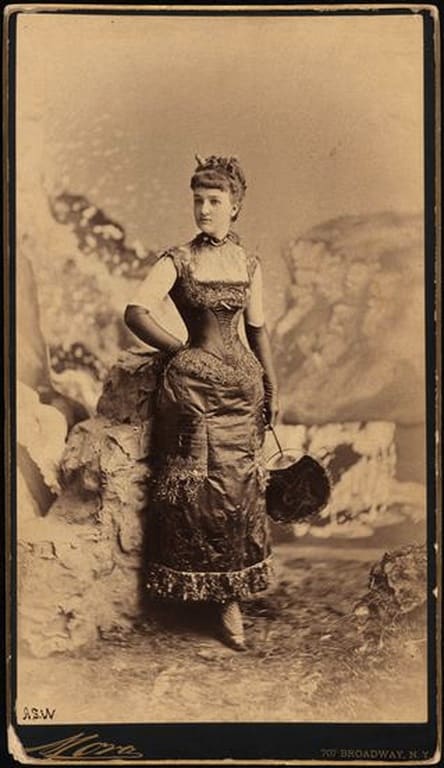

Much like at the prom, the guests had the opportunity to have their photo taken at the event of the year, or perhaps the century, by Mora, a Cuban refugee who was the photographer of the rich and famous.

Cornelius and Alice Gwynne Vanderbilt II as Louis XVI and the Electric Light.

Museum of the City of New York

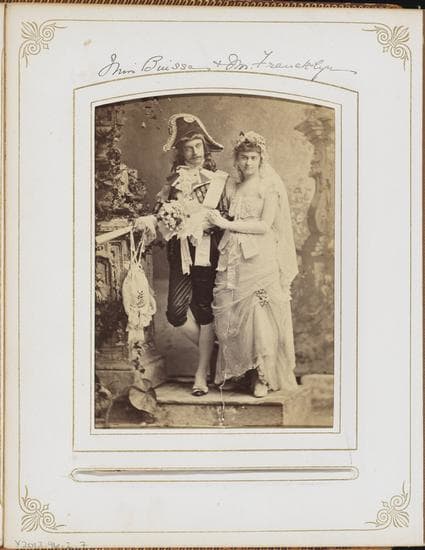

Engaged couple Agnes Binsse and Reginald Francklyn, dressed as Incroyables, a reference to French society.

Museum of the City of New York

Alva dressed as a Venetian Renaissance lady, while her sister-in-law, Mrs. William Seward Webb, went as a hornet and wore an imported headdress made of diamonds.

Other guests included Miss Edith Fish dressed as the Duchess of Burgundy, with genuine emeralds, rubies, and sapphires adorning the front of the dress, and Miss Kate Fearing Strong, who dressed as her nickname “Puss” and wore a disturbing costume that consisted of seven cat tails sewn onto her skirt and a taxidermy cat head she wore as a hat.

Miss Edith Fish was dressed as the Duchess of Burgundy, with real sapphires, rubies and emeralds studding the front of the dress.

Museum of the City of New York

Mrs. William Seward Webb (neé Lila O. Vanderbilt), dressed as a hornet and wearing a headdress of diamonds.

Museum of the City of New York.

One of the most dazzling costumes of the ball was worn by Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt II. Designed by Charles Frederick Worth, her costume, representing “Electric Light,” was made of yellow satin and gold and silver thread and decorated with glass beads and pearls in a lightning-bolt pattern. It even had a torch that lit up, thanks to batteries hidden in her dress.

Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt (Alice Claypoole Gwynne) as “Electric Light” in a costume designed by Charles Frederick Worth. A built-in battery lit a light bulb she carried and could raise over her head like the Statue of Liberty.

Public domain photo/Wikimedia Commons

The yellow satin Electric Light dress designed by Charles Frederick Worth. It’s decorated with glass pearls and beads in a lightning-bolt pattern. This dress was only one of several spectacular gowns that served to make the event the official start of Alva Vanderbilt’s role as a leading socialite of New York. The dress is preserved at Museum of the City of New York.

Museum of the City of New York

At 11:30 sharp, the ball officially began with the hobby-horse quadrille, and guests danced down the mansion’s grand staircase in their lavish costumes. Dancers in the Dresden quadrille wore all-white court costumes and looked like porcelain dolls. The costumes were just as elaborate for the Opera Bouffe quadrille. Miss Bessie Webb, dressed as Mme. Le Diable was described in the New York Times as being “in a red satin dress with a black velvet demon embroidered on it and the entire dress trimmed with demon fringe – that is to say, with a fringe ornamented with the heads and horns of little demons.”

As part of the Dresden quadrille, John E. Cowdin also looks like a white porcelain doll.

Museum of the City of New York

Miss Elizabeth “Bessie” Remsen Webb, she of the demon-themed costume.

Museum of the City of New York

The ball went into full swing after the quadrilles ended. Dozens of Venetian noblewomen and Louis XVIs, Joan of Arc, a King Lear “in his right mind,” and hundreds of other costumed guests drank champagne and danced around the flower-filled house and the third-floor gymnasium, which had been converted into a forest filled with orchids, bougainvillea, and palm trees. A small staff of servants served dinner at 2 a.m., including chicken croquettes, Maryland-style terrapin, fried oysters, beef, ham and chicken in jelly, salmon a la Rothschild, chicken salad au celery, sandwiches a la Windsor, and several kinds of ices.

The dancing continued until sunrise when Alva led her guests in a final Virginia reel. Then, just like that, the grand ball was over. Men in powdered wigs stumbled down Fifth Avenue toward home, and Alva’s fantasy world turned back into reality.

Most contemporary sources put the cost of the ball at $250,000 (around $6 million in today’s money), including $65,000 for champagne and $11,000 for flowers. All of the extravagant pomp and pageantry worked: Newspapers across the country praised Alva’s tastes and classiness and reported the most minute details. There was some backlash, however. The New York Sun published an article that took issue with all of the excess when there was so much suffering in the same city:

“Some kind-minded persons argue that entertainments of this kind are both charitable and patriotic, for they cause money to circulate and give work to those whose lot it is to toil. This is sentimental rubbish. The needy American workingman and workingwoman do not make a cent by the importation of Worth’s dresses, the purchase of new diamonds at Tiffany’s or the resettling of old family jewels … the festivity represents nothing but the accumulation of immense masses of money by the few out of the labor of many.”

Miss Elizabeth “Lizzie” Pelham Bend, dressed as Vivandiere du Diable possibly for the Opera Bouffe quadrille.

Museum of the City of New York

But we’re guessing that all the party revelers, especially Alva herself, gave not one whit about what The Sun thought of her extravagant costume ball because, as of March 27, 1883, the Vanderbilts were on The List that was no longer limited to 400 people.

Perhaps that’s why Mora later added birds to Alva’s photo – to symbolize that she was finally flying as high as the other social elites.

You can see more extravagant ball costumes in the photo album at The Museum of the City of New York.

You might also like:

Rare Callot Soeurs Gowns Found in Trunks

How a Little Black Dress Scandalized Paris in 1884

Inside the Closet of Marjorie Merriweather Post