“I never wanted the world. Just enough room for both of us.”

Mike Hammer has an odd film history, especially compared to other classic detectives. He toiled away in B-movie adaptations while PIs like Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe got the A-list treatment. kiss me deadly (1955) is the lonely Hammer film that is considered a masterpiece, but even then the treatment of the Hammer character and the plot as a whole has been radically altered from the novel.

The author behind Hammer, Mickey Spillane, hated it kiss me deadlyand later attempted to negate the film’s impact by starring in his own vehicle, The girl hunters (1963). It was a decent translation, but in his later years Spillane himself admitted that it lacked style. In truth, the only film adaptation he praised highly was the first: I, the jury (1953). Overshadowed by the legacy of the above films, I, the jury remains the most authentic Hammer experience ever brought to the big screen.

The film’s authenticity can be traced back to its creators. Victor Saville was a producer who saw a cash cow in Spillane’s paperbacks and felt that if properly adapted, her mix of sex and violence would be undeniable. Harry Essex was a screenwriter who helped shape the terrain of 1950s film noir, and he knew exactly how to create suspense from predictable story beats. He was also keen on directing and saw I, the jury as a chance to show off your talent.

As someone who was blown away by the film upon first viewing (kiss me deadly was my only point of reference then), I can say that now I, the jury is the perfect introduction to Hammer’s world. There is so much effort to emulate the style of the novel that the character’s narration seems like she is reading the actual pages. Essex proved to be a frugal storyteller with the screenplays for Kansas City Confidential and The Las Vegas Story (both 1952), but here he arranges scenes with surgical precision. It’s as if the need to reduce the sex and violence found in the novel allowed Essex to speed up an already meager narrative, and the result is a breakneck 87 minutes.

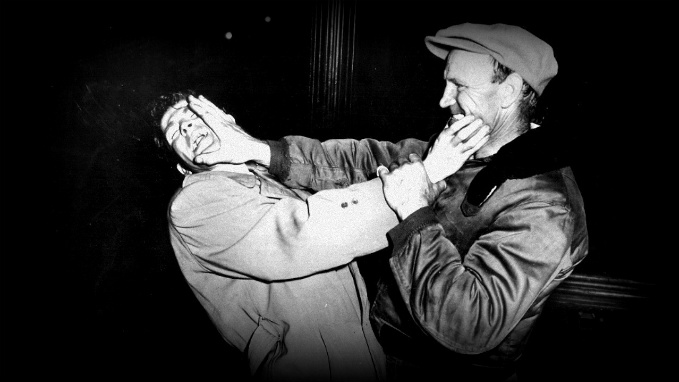

The story is really just a premise: Hammer (Biff Elliot) finds out that his old army buddy Jack Williams (Robert Swagnar) has been mysteriously killed in his apartment. The bull then proceeds to destroy the china shop in New York while trying to find William’s killer and make her pay for it. Along the way, Hammer runs afoul of a wily therapist (Peggie Castle) and a lunatic crime boss named Kalecki (Alan Reed).

Elliot wasn’t a versatile actor, as evidenced by his relatively quiet career, but he’s effectively cast here. He does a good job of capturing Hammer’s blunt approach to recognition, and his ability to appear dense and thoughtful at the same time is more difficult than it might first seem. It’s nothing remarkable, especially compared to the heightened vanity Ralph Meeker brought to the role kiss me deadly, but it’s direct and visceral. Elliot’s choices look even better in comparison to Robert Bray’s softer, less edgy performances My weapon is fast (1957) and Darren McGavin in the television series Mike Hammer from Mickey Spillane (1957-59).

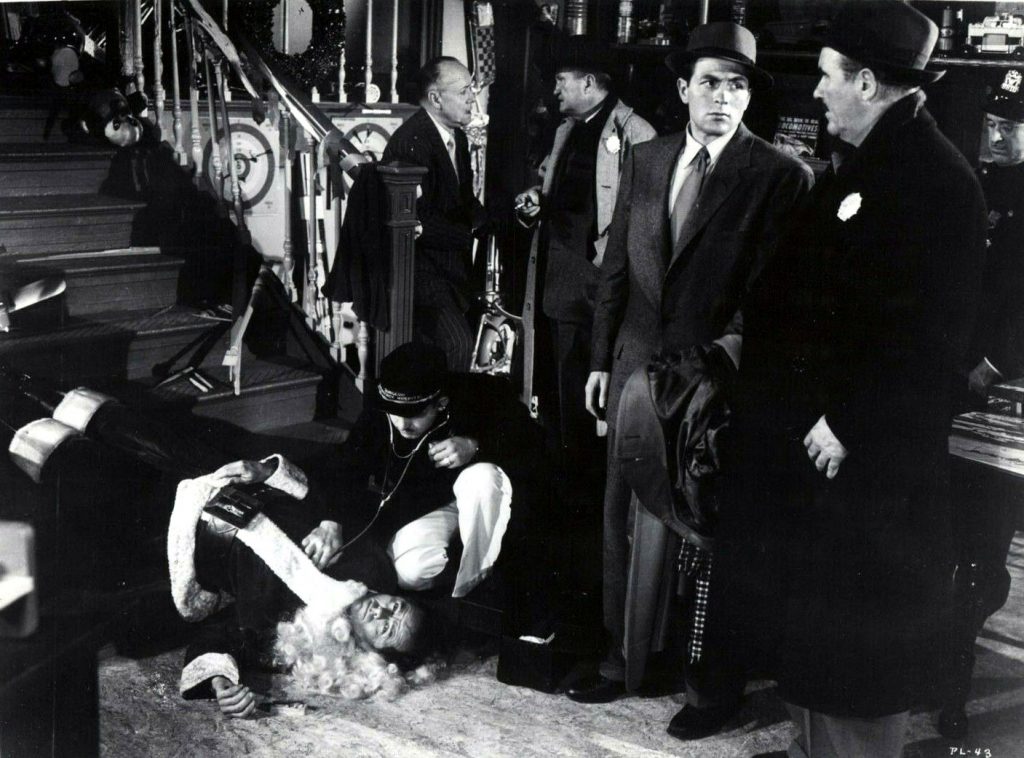

The supporting cast consists of reliable character actors, starting with the aforementioned Castle (the self-proclaimed “girl they like to kill”) through to Preston Foster as Hammer’s steadfast police liaison, Pat Chambers. They rattle off the terse Spillane dialogue with glee while drawing on the two-dimensional aspects of their respective characters. Nobody does it better than Elisha Cook, Jr. as Bobo, a simpleton who manages to win us over despite his ties to a deadly gang. The shot of a slain chef lying on a staircase dressed as Santa Claus is arguably the most noirical Christmas image of all time.

The stunning images don’t stop there. I, the jury may benefit from tight direction and a colorful cast, but it’s John Alton’s cinematography that really pushes it into cult-classic territory. The film unveils one entrancing sequence after another, be it the pulsing neon conversation in Hammer’s office or the single-light interrogation conducted by Kalecki’s men. Added to this is the 3D component that Alton had to take into account during production. The film was originally made to capitalize on the 3D craze of the 1950s, and the cinematographer’s skillful use of cigarette butts and various spatial structures gives the film a subtlety and cleverness that few 3D releases can match. The fact that it works in both 3D and 2D versions is a testament to its overall quality.

Then there’s the end. Hammer navigates a tangled web of lies and murder and finds himself in his therapist Squeeze’s apartment. He has found out about her involvement in William’s death and holds a gun on her from the moment she enters. She continues to undress, partly for convenience and partly to try to seduce him. The dialogue intensifies, with both characters’ emotions bubbling ever closer to the surface. Alton’s camera locks on the couple during their final embrace, and then we hear a gun firing under the frame. It’s unclear who was shot until the therapist falls to the ground. “How could you?” she asks, to which an intrepid Hammer says, “It was easy.”

It’s a stunning scene that manifests all the sex and death, and that’s what makes the Hammer novels so compelling. It’s the best distillation of the character and his distanced worldview yet, and for Alton one of his best visual showcases of all time. That alone would justify the price of admission.

I, the jury should not be considered a masterpiece. It’s a cheap film noir that wants to entertain, and that’s exactly what it does. Approaching the film from these very simple bases will leave you immensely satisfied.

…..

All articles from Danilo’s Film Noir Review can be found here.

Danilo Castro is a Film Noir fan and contributing writer for Classic Movie Hub. You can read more articles and reviews by Danilo at the Film Noir Archive or follow Danilo on Twitter @DaniloSCastro.