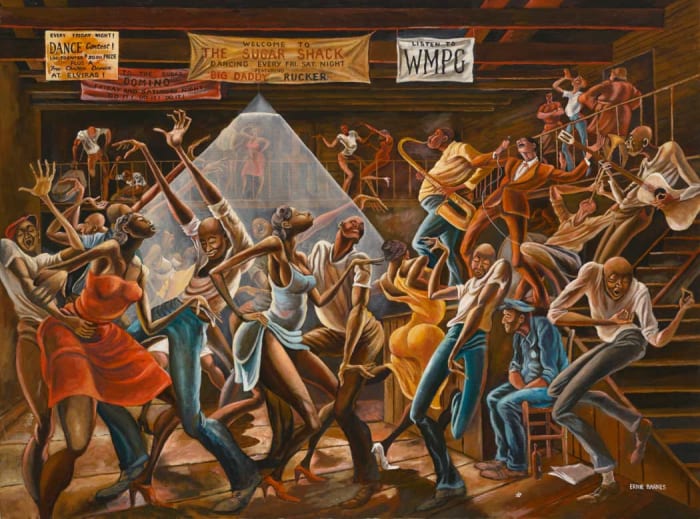

A celebration of the joy found in dance, The Sugar Shack, by American artist Ernie Barnes, shimmied off as the biggest surprise of Christie’s 20th Century auction May 12, selling for $15.3 million, or 76 times its high estimate of $200,000.

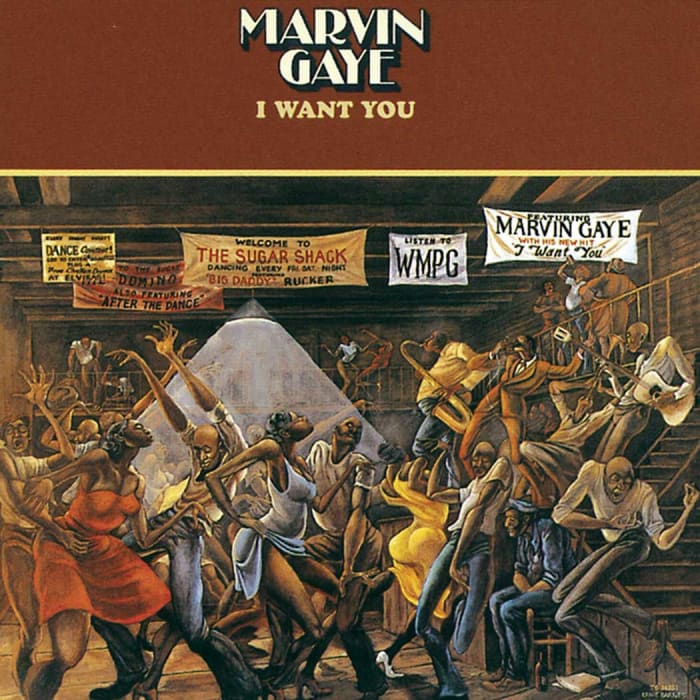

The painting was featured on the cover of Marvin Gaye’s album, “I Want You,” and during the closing credits of the 1970s hit TV sitcom “Good Times.”

Although the painting sold well-past its pre-auction estimate, Bill Perkins, the 53-year-old energy trader who purchased the 1976 painting, told The New York Times, “I stole it – I would have paid a lot more. For certain segments of America, it’s more famous than the Mona Lisa.”

Bill Perkins and fiancé Lara Sebastian with Ernie Barnes’ ‘The Sugar Shack’ at Christie’s. Perkins paid $15.3 million for the 1976 painting.

Courtesy Bill Perkins

The sale reflects a heightened interest in work by Black artists. Just last November, Barnes’ 1978 painting Ballroom Soul sold for $550,000, a short-lived record for the artist.

Also making news at the Christie’s event, Washington Crossing the Delaware – perhaps the most recognizable painting in U.S. history, sold for more than $45 million. The 1851 painting by Emanuel Leutze hung in the White House from the 1970s to 2014. It is one of three versions painted by Leutze, famously capturing the moment when General George Washington boldly led his troops across the half-frozen Delaware River to Trenton, New Jersey on Christmas night 1776. Pre-auction estimates for the painting ranged between $15-$20 million.

‘Washington Crossing The Delaware’ by Emanuel Leutze sold for more than $45 million.

Courtesy of Christie’s

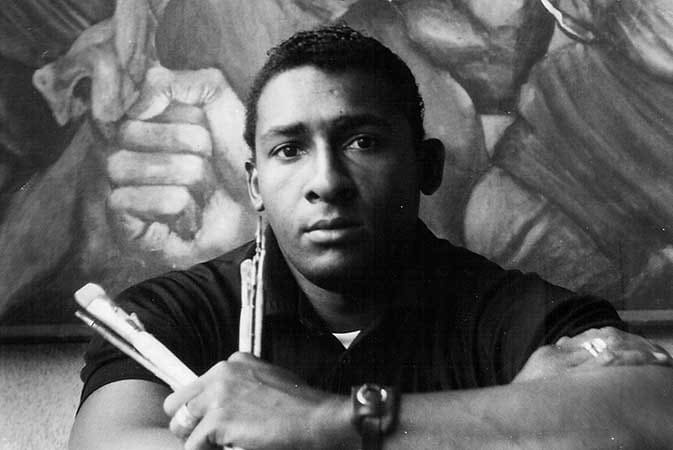

Barnes, who died in 2009, was born in North Carolina in 1938 and often drew upon his own experiences growing up in the American South during the Jim Crow era in his depictions of social moments and images of every day Black life. The painting draws from Barnes’ own memories of the Durham Armory in 1952, an iconic dance hall in segregated North Carolina. The artist snuck into the Armory as a kid, forging a memory of music and movement that would inspire the creation of The Sugar Shack.

Artist Earnie Barnes (1938-2009) was well known for his unique style of elongated characters and movement.

Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History

In a 2002 interview, in which the Oakland Tribune described Barnes as the “Picasso of the Black art world,” the artist said he got the idea for The Sugar Shack from reflecting on his childhood and “not being able to go to a dance I wanted to go to when I was 11.”

Perkins told Artnet News he has mixed feelings about the historic undervaluation of work by African American artists.

“As a novice, I’m buying what I like,” Perkins said. “There is American art, and there’s Black art and Black artists, and it’s like this sub-category. I don’t know all the reasons, I think collectors before thought, ‘Well I’m going to support this,’ and there was this kind of charitable endeavor to it. When I came along, I’m thinking, ‘These are basically free.’ This is such an integral, foundational part of history. Black history is why America is an empire. These stories are important, but it’s as if people have been put it in this other category.”

The pure and unadulterated bliss of dancers captures the imagination in Earnie Barnes’ The Sugar Shack’.

Courtesy of Christie’s

In its catalog essay of the painting, Christie’s described the images of dancers as emanating “pure, unadulterated bliss, a joy that perhaps echoes that of worshippers caught in the throes of religious ecstasy. With the visualization of such passion, Barnes artfully infuses the painting with both a core of gravity and an embrace of the carefree.”

“The unique enchantment of this work,” Christie’s wrote, “can be located in its ability to envelope the viewer wholly into the heat, song, and energy of the scene it illustrates.”