“Run faster, Joey! The Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey Circus is unloading from the train. I hear it’s the ‘Greatest Show on Earth.’ Did you see that poster in McCaskey’s candy store window of that acrobat balancing on one finger? That’s amazing!”

It was the late 1930s. Practically the entire town had closed for the most spectacular event of the year. A parade of wagons rolled into town, carrying a huge, menacing gorilla; unusual, exquisite camels, and snarling tigers that jumped through hoops of fire. The townspeople had never seen the likes, and many would never see anything as amazing again.

“Come on, Joey! Run!”

The first U.S. circus was established in Philadelphia in 1793, but it wasn’t until the introduction of the tent in 1825 that the circus became a truly roving art form. The arrival of P. T. Barnum in 1871 transformed the trade and five Ringling brothers – Albert, Otto, Alfred, Charles and John – created a spectacle all their own.

For more than a century, “Circus Day” was as anticipated as Christmas and the Fourth of July rolled up into one otherworldly event. Colorful and brash, the circus rolled into town and crashed into everyday life – and disappeared just as quickly. The circus grew with the country, evolving into a massive entertainment industry of exotic animals and dazzling performers.

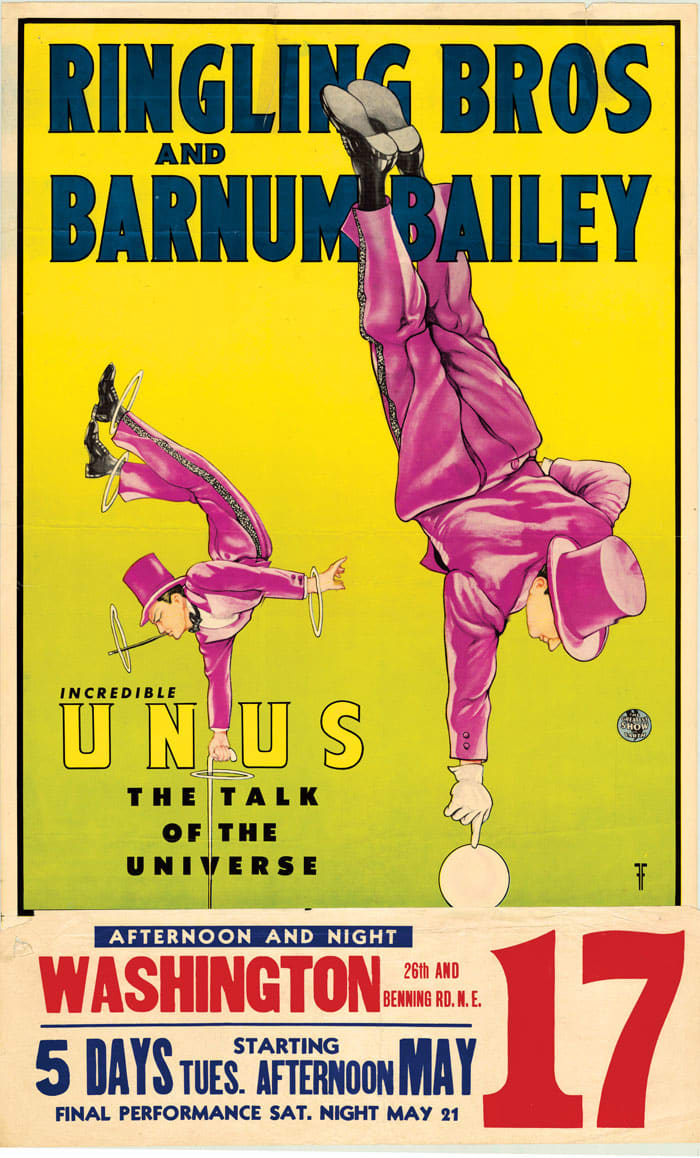

The Austrian Franz Furtner, or “Unus,” star acrobat of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey show, debuted his act in 1948.

Chris Berry Collection

Although the Great Depression and competition from radio and movies dimmed the extraordinary heyday of the circus, the magic of the era lives on.

Collecting circus items remains a vibrant and colorful hobby, especially paper products—photographs, posters, literature, business records—and artifacts. The grandiosity of the Big Top, with its music and artistry, resonates still in the heart of every collector.

Brian Hollifield is co-owner of Freedom Auction Co. out of Sarasota, Florida, which also holds circus, carnival, sideshow and oddity auctions via circusauctions.com. His joy is connecting collectors with circus history.

“I joined the Circus Historical Society because I was looking to be more accurate with the auction house catalog to tell the tale of the artifact,” Hollifield said. Knowing the history of a piece enriches value and meaning, as well as providing a better understanding of the field.

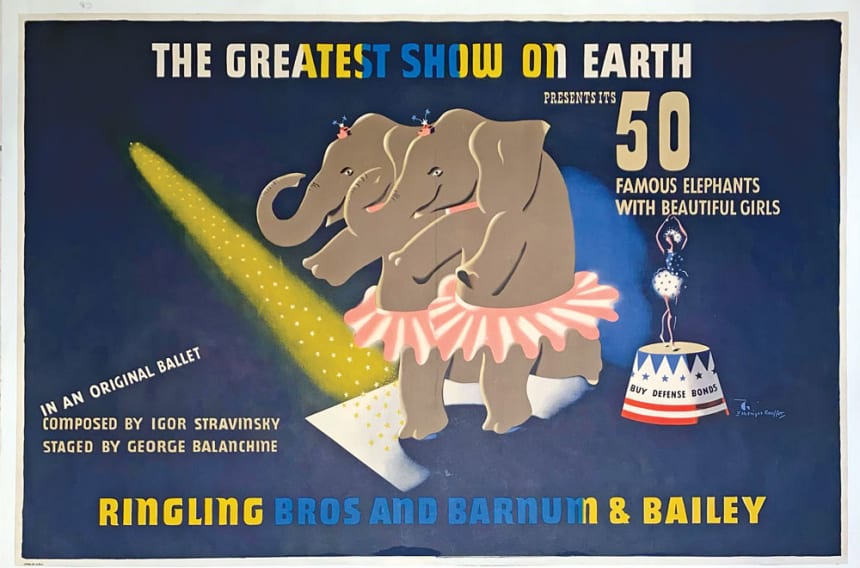

The American artist Edward McKnight Kauffer designed this delightful 1942 “Elephant Ballet” poster for the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey combined show. Igor Stravinsky composed the music and George Balanchine, one of the most influential choreographers of the 20th century, staged the performance.

Chris Berry Collection

For example, Jack LeClair, a well-known twentieth-century clown, drew a schematic of a “fat suit,” for himself. If a collector obtains the “fat suit,” a photograph of the clown wearing it, and LeClair’s schematic, “that’s auction magic,” Hollifield said, telling the story when the clown wore the outfit, why he wore it, and its historical significance.

“The demand for circus memorabilia has skyrocketed in recent years because of a combination of nostalgia and recognition of the unique artwork that was created in those days of mass market,” said Chris Berry, Vice-President of the Circus Historical Society.

Berry specializes in circus posters and has one of the largest private circus poster collections in the United States, with hundreds of rare and hard-to-find – and highly collectible – lithographs dating back to the 1850s. Few people collected circus posters back in the day before the 1930s. “Many early posters don’t exist anymore because they weren’t meant to be saved,” Berry said.

For example, P.T. Barnum’s advance team would plaster thousands of posters on anything standing still within a twenty-five-mile radius of circus venues leading up to the event. But these colorful, vibrant posters slapped on barns, sheds and shop windows were only expected to survive a couple of weeks.

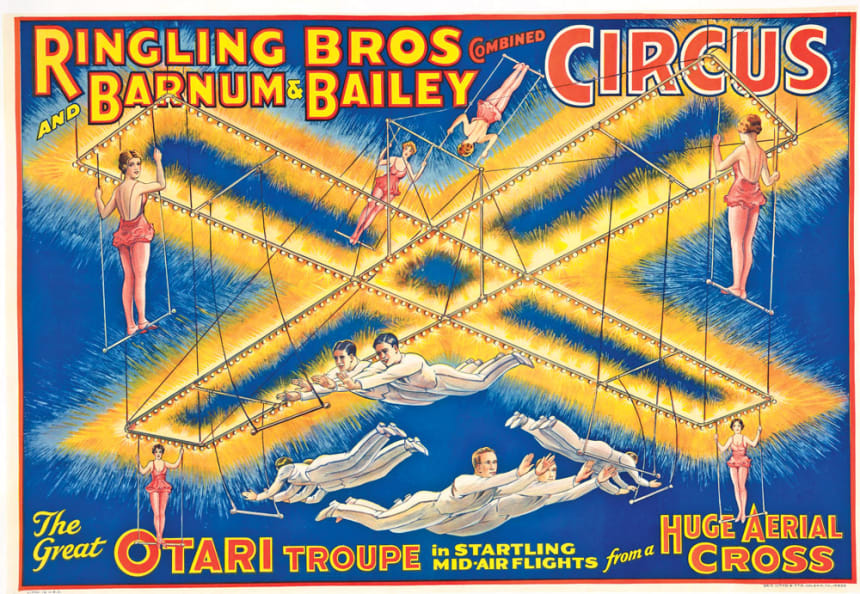

The Great Otari Troupe Act of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Combined Circus lit up a show with a huge aerial cross act done with black lights and special rigging. This circa 1936 Erie Lithograph poster captures the stunning mid-air flight moment perfectly.

Chris Berry Collection

The Courier Co. in Buffalo, New York, produced many of these posters, but a 1908 fire destroyed most of its large presses, ending their operations, making these posters rare and very valuable.

Circus posters from the 1930s and ’40s are excellent to collect. Although most were used, many remain. Berry said, “The value of these posters has shot up in recent years,” Berry said. “An excellent starting price for a one sheet ’30s authentic poster is $600 whereas 15 years it acquired $300.”

Reproductions, however, run rampant. Most replicas are from after the 1960s. In the 1970s, the Ringling Bros. sold reproductions at performances. Berry suggests collectors always check poster dimensions. “An authentic poster measures 42 inches long by 28 inches wide for a one sheet or has dimensions of multiples or fractions of that,” he said.

Check if a poster has a “P” letter in its margin followed by a stock number. An authentic circus poster does not. Lastly, using a jeweler’s loupe, examine the poster. A reproduction will have pixelation.

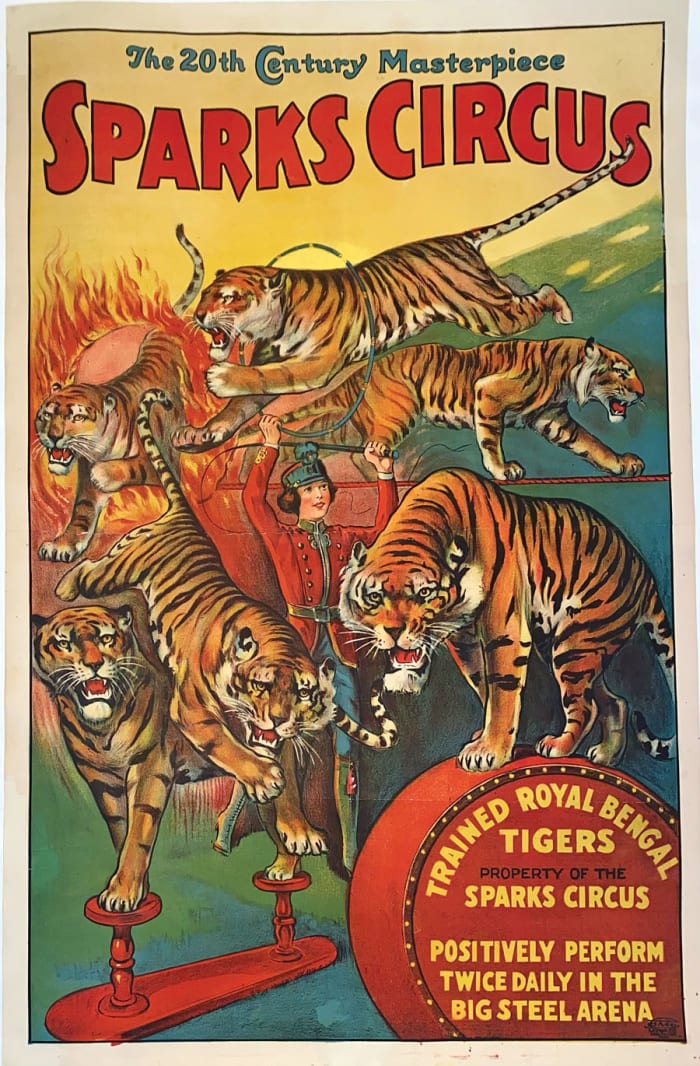

This 1928 Erie Lithograph poster for Sparks Circus is unique, featuring a female trainer in the middle of the tigers. There were few female trainers at the time; one of the most famous was Mabel Stark.

Chris Berry Collection

Both Berry and Hollifield recommend fans collect for visual or historical appeal, not for investment. The adage of collecting what you like applies to circus items. What is in vogue today may not be so tomorrow.

“Do study the condition of the item to make sure it meets your expectation and consider who is selling it to you,” Hollifield said. Only a few auction houses specialize in circus memorabilia or have extensive knowledge about it. Freedom Auction Co., one of them, will have circus auctions on July 10 and August 6. The August auction will feature the Gordon Turner circus collection.

Preservation is critical for all collectors. “Do so by showcasing it,” Hollifield said, “and then tell your family members that it’s special. You don’t want them to give it to Goodwill when you aren’t there.”

Researching a collection can be rewarding, but an even greater thrill is to experience the circus in person. Berry said that there are over 50 circuses across the U.S. After ending its 146-year run in 2017, the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus is returning in 2023, but without animal acts.

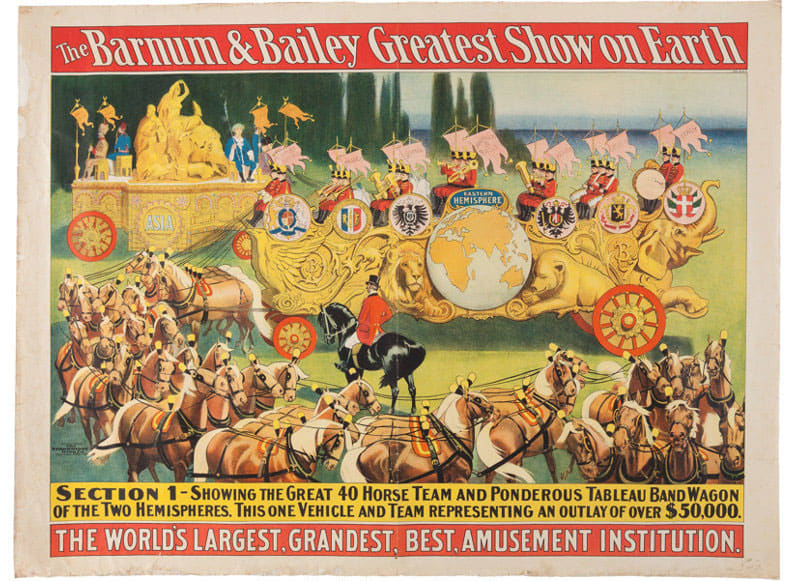

The beautiful Barnum & Bailey’s “Two Hemispheres Circus Bandwagon,” debuting in 1903, is the largest bandwagon ever built at 28 feet and 6-1/2 tons. Harry Ogden of Strobridge Litho. Co., Cincinnati, Ohio designed it. Sebastian Wagon Co. of New York fabricated it with both Samuel A. Robb and the Spanjer Co. of Newark, NJ supplying the massive wood carving bas reliefs of “continents” on the either side of the wagon. Canadian circus historian Peter Gorman purchased it at Heritage Auctions in 2016 for a record $250,000. Currently, it is appraised at more than $1 million.

Courtesy of Heritage Auctions

Another option is to take in Circus World Museum in Baraboo, Wisconsin, home of the Ringling Bros. Circus. Baraboo plays host to a three-day, pirate-themed circus weekend at the end of June, with a Big Top Parade Saturday, June 25, featuring circus wagons, marching bands, animals and clowns.

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th century, the Ringling show returned to Baraboo at the end of its tour to prepare for the next season. The winter months were busy, repairing and repainting equipment, designing and fabricating props and wardrobe, contracting performers, planning the route, contracting railroads to haul the train, and pulling together artwork for new advertising campaigns. Workers also cared for animals, which in 1916 consisted of: five hundred horses and ponies, 29 elephants, 15 camels and about 20 other hay eating animals, plus tigers, lions, monkeys, and birds including ostrich.

This colorful and rare 1903 Barnum & Bailey Circus poster features the “Two Hemispheres” Bandwagon debut in the grand parade held to celebrate the return home of the “Greatest Show on Earth” after the circus’ triumphal five-year world tour. Printed by the Strowbridge Litho Company of Cincinnati, this sold at auction in 2016 for $2,500.

Courtesy of Heritage Auctions

Of the 25 Ringling structures that once existed in Baraboo, ten winter quarters buildings remain – all National Historic Landmark Structures. They are the largest grouping of circus structures in America.

Circus World’s pride and joy is the largest collection of authentic circus wagons on earth. This colossal congress contains more than 260 wagons and vehicles from large, medium and small shows as well as carnivals.

“Circus World is really a cultural heritage institution because the circus is still here today,” Museum Archivist Peter Shrake said.

Sources

The Circus Historical Society is dedicated to preserving the rich history of

the circus. The Society’s membership includes a diverse selection of scholars, researchers, educators, archivists, curators, librarians, circus professionals and enthusiasts united with the common goal of documenting circus history and sharing circus information. Bandwagon, the Society’s journal, is distributed to all members as well as to research institutions worldwide. Online resources include a fact filled website, periodic newsletters and archival documents. This year’s annual convention is July 24-26 in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, Florida

The Milner Library, Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois

The Robert L. Parkinson Library and Research Center, Baraboo, Wisconsin