Miriam Haskell is a perennial favorite among collectors of vintage costume jewelry. Even a single strand of faux baroque pearls is noteworthy with a Haskell mark, and the more elaborate styles made by this company can indeed bring top dollar.

So, who was Miriam Haskell? Many people refer to her as if a single woman crafted every piece of jewelry with her name on it. No one really knows how many pieces she actually produced with her own hands, but the consensus among jewelry historians is not much.

Prior interviews with former employees and old-timers in the industry point to Haskell being a businesswoman based in the bustling city of New York first and foremost. And, she did have the good sense to hire a terrific designer to help her grow her company during its early years.

Model Mary McLaughlin with faux moonstone necklace, and earrings by Miriam Haskell, in a 1957 cover photo shoot for Vogue.

Joseph Leombruno/Condé Nast via Getty Images

Haskell History through the 1960s

Haskell hired Frank Hess as a jewelry designer shortly after opening her first shop in the McAlpin Hotel in in the late 1920s. Hess, who had been working for Macy’s as a window dresser, learned the ropes and quickly became the heart of creativity for the firm.

Through the 1930s, Miriam Haskell – the business – grew and flourished. Jewelry made by the company was popular both in the United States and abroad. This acceptance was fueled in part by movie stars being photographed in Haskell pieces, and they were also worn in a number of stage and screen productions of the day.

Things rocked along for Miriam Haskell through the 1940s and the business met the challenges of the war years in some truly creative ways. Haskell’s health began to decline, however, and she relinquished control of her business to her brothers in 1950. Hess stayed with the firm until 1960 when he left to form the Morton Hess company with Haskell’s nephew, Josef Morton Glasser.

An important fact to remember about Miriam Haskell jewelry from the late 1920s through the late 1940s is that Hess designs made during this period were unmarked. If a piece of Haskell has a correct mark, it was made after 1947. The earliest mark used was Miriam Haskell in a circle stamped into the metal. Beginning in 1948, what collectors call the “horseshoe” mark was used for a couple of years (although a handful of backstock horseshoe plaques were affixed to a few pieces in later decades.) Thereafter, the more familiar Miriam Haskell oval cartouche was used.

Haskell’s Signature Style

When most people think of Haskell, faux pearls immediately come to mind. The company did use a tremendous number of high-quality simulated pearls in their pieces, especially seed pearls and larger baroque pearls imported from Japan, but there’s much more to the story. Some of the most beautiful Haskell designs are made up of colorful imported glass beads and rhinestones, including flat-backed rose montees in clear and colors.

While many of the components were die-stamped metal, including filigree backings used extensively from the late 1940s on, each piece displays hand-manipulated construction whether in an intricate necklace centerpiece or a bracelet clasp. Individual components were wired together by hand and the backings hid the evidence beautifully so that each piece appears nicely finished on the reverse. Haskell beaded necklaces were also made using a technique called back stringing giving them a quality touch above other strands of beads.

In contrast, during the World War II era traditional materials were hard to come by so alternatives like wooden beads, genuine seashells, and plastic elements were used instead. These were sewn or affixed to woven cord to fashion necklaces and bracelets. Brooches and clips had the decorative components sewn or wired onto disks made of plastic or perforated metal. All these pieces were unmarked, which can further throw collectors trying to identify them because many can be quite sloppy when viewed from the back.

The real pitfalls of Haskell jewelry, however, are the damage issues that come along with it. Pieces that combine brass wiring with faux pearls are notorious for having verdigris present – a bright, bluish-green encrustation or patina caused by atmospheric oxidation. This causes the wiring to break and tiny components are easily lost. Hard to clean verdigris can also be present on tiny spacer beads, especially when it comes to faux pearl necklaces. Bottom line, many Haskell designs are intricately crafted and need to be very carefully examined for damage before making a purchase.

Other Noteworthy Haskell Designers

After Hess left Haskell, Robert Clark became the lead designer for the company. While not as well-known as some other heads of Haskell’s design team, he did sketch a number of popular collections. He stayed with the firm through the late 1960s and then partnered with William DeLillo to start a new business. Peter Raines briefly took his place when he left.

After Raines came Lawrence Vrba. Known by his friends as Larry, this designer is credited for the tremendously popular Egyptian revival jewelry sold by Miriam Haskell during the mid-1970s. He also veered in a different direction by using alternative materials like wood, shells, and natural stones in some of his in his pieces to appeal to a new generation of consumers. When Vrba left to pursue his own business in 1978, Millie Petronzio quite capably took over Haskell’s design team refocusing on more traditional Haskell styles.

All these designers carried on the tradition of incorporating quality components and skilled craftsmanship into Haskell jewelry while adding their own vision to the designs. Even into the 2000s, quality faux pearls were used along with other impeccable touches on the company’s high-end lines.

However, some collectors feel the business “sold out” during this later period by allowing the name M. Haskell to be used on lower quality mass-produced department store jewelry. Most of the time it is easy to tell these pieces apart from Haskell’s more luxe lines since the quality doesn’t compare. Another clue is that these lesser pieces usually do not have the classic Miriam Haskell oval mark.

Learning More About Miriam Haskell Jewelry

While several books have been written on Haskell over the past few decades, one of the best available is Miriam Haskell Jewelry (Schiffer, $59.99) by Cathy Gordon and Sheila Pamfiloff. These authors provide a great overview of the company by including information on the components used, the work of the designers, and how to recognize reworked and mis-tagged Haskell pieces. The details on identifying early, unmarked Haskell jewelry alone is worth the price of the book.

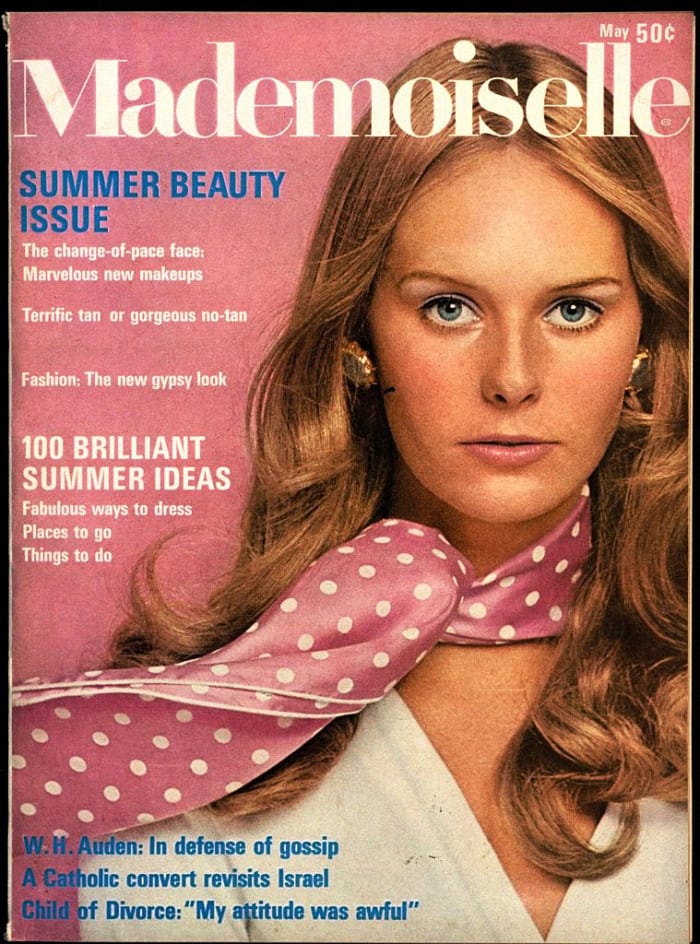

Mademoiselle cover from May 1968 wearing faux pearl and gold earrings from Miriam Haskell.

Photo by David McCabe/Condé Nast via Getty Images

You May Also Like:

How to Identify Juliana Jewelry