“An innocent man has nothing to fear, remember.”

Alfred Hitchcock was nothing but a playwright. He loved taking trivial takes and flooding them with so much excitement that something as trivial as delivering a glass of milk or spying on a neighbor could be a matter of life and death. After all, he was the “master of tension”. What then becomes of Hitchcock when he is forced to temper his over-the-top tendencies and tell a true story? The answer can be found in the wrong man (1956).

the wrong man is an outlier in many ways. It’s the only Hitchcock film directly based on true events (others have drawn inspiration from real life), the only one to eschew traditional set pieces, and the only one to carry the director’s trademark “mistaken identity” to its darkest and most logical end explored . the wrong man is a devastating viewing experience when stacked against the cheeky thrills of North for Northwest (1959) or the salon intrigue of Select “M” for Murder (1954), and much of it has to do with his film noir ethos.

Hitchcock and Noir ran side by side in the 1940s and 50s. They only occasionally overlapped, and when they did, a la hint of a doubt (1943) or strangers on a train (1951) they still gave the audience a vicarious jolt. They might have the window dressing of film noir, but they were thrillers at heart. the wrong man bucked this trend. It was Hitchcock who embraced the relentlessly dark, and it holds up remarkably well for being one of his less celebrated releases.

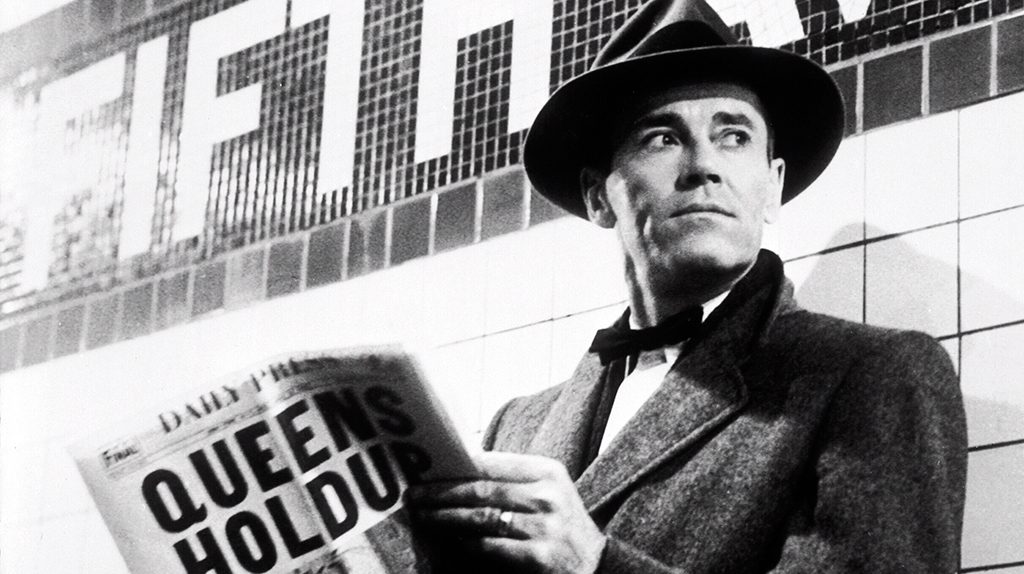

The film revolves around Manny Balestrero (Henry Fonda), a jazz musician who never made it big. He makes a miserable living at the Stork Club in New York, but he still needs an inflow of cash if he is to help his wife Rose (Vera Miles) pay for dental treatment. He visits an insurance company hoping to strike a deal, but there he is identified as the man who previously robbed the company twice. He will be taken into custody at the end of the night.

Manny’s arrest is one of the most chilling scenes of Hitchcock’s entire career. There are no stabbings or sudden bird attacks, but the depiction of his booking, fingerprinting, and subsequent imprisonment is so unflinching that it borders on cruelty. We’re forced to sit and watch Manny (and Fonda, one of our favorite American actors) being treated like a mean crook, even though we know he’s innocent. It’s maddening, and the film knows it.

Fonda is intrigued by what turns out to be his only collaboration with Hitchcock. From the moment he steps into the frame he exudes a layered decorum, and the quiet dignity he musters despite being forced to endure countless humiliations is something that cannot be taught. Take, for example, the moment when he is handcuffed. While it could easily have been hyped for dramatic effect and used as a stepping stone to a Brando-esque meltdown, Fonda prefers to keep things subdued. He simply looks down at his bound wrists and lets the sadness in his eyes communicate what we already know to be true.

Another standout moment is when Manny is put behind bars. Hitchcock’s camera launches through the slot in the prison cell, and what we find at the other end is a man with his back to us. We see a slight head tilt, then a hit head. There’s a sense of moral humiliation that runs through Fonda’s performance, and that’s what makes it the wrong man at the same time powerful and yet difficult to observe.

Hitchcock seemed an odd choice to delve into the material adapted from the Maxwell Anderson novel The true story of Christopher Emmanuel Balestrero, but in truth he wanted to tell this story all his life. Hitch’s upbringing was coupled with a crippling fear of the police, which many attributed to the night his father decided to punish him by sending him to jail for the night. The police are not demonized the wrong man, but they are viewed as intimidating forces that wield their power much more callously than they should. Manny’s wife is brought to the brink of sanity and more throughout the course of the film, and the police do little to allay her concerns or even suspect that Manny may be innocent.

The aesthetic choices support this unwavering perspective. The rich color palette that adorned Hitchcock’s previous films is replaced with high-contrast black and white. The lavish crane footage is abandoned in favor of a gritty, documentary approach that makes the whole thing feel like an A-list newsreel. In addition, there is the jazzy score by Bernard Herrmann. The composer was Hitchcock’s most important collaborator during his most prolific period and during the wrong man While it may not reach the heights of his other hit-scores, Herrmann gives the film exactly what it needs.

I won’t pretend the wrong man is Hitchcock’s crowning achievement as a filmmaker, or that he’ll be at the top of anyone’s list when it comes to listing his masterpieces, but there’s some evidence that if it were made by any other filmmaker it would rank as a minor classic. the wrong man is creatively enhanced by Hitchcock’s involvement but commercially hampered because fans always expect something sophisticated and entertaining.

It’s left turns like this that would eventually allow Hitchcock to hit pay dirt Psycho (1960), a film that doesn’t just recycle the wrong man‘s casting by Vera Miles, but the black and white cinematography and moral indifference. It’s worth revisiting as the most blatant film noir of the director’s entire career.

TRIVIA: the wrong man features early uncredited performances by actors Tuesday Weld and Harry Dean Stanton.

…..

All articles from Danilo’s Film Noir Review can be found here.

Danilo Castro is a Film Noir fan and contributing writer for Classic Movie Hub. You can read more articles and reviews by Danilo at the Film Noir Archive or follow Danilo on Twitter @DaniloSCastro.