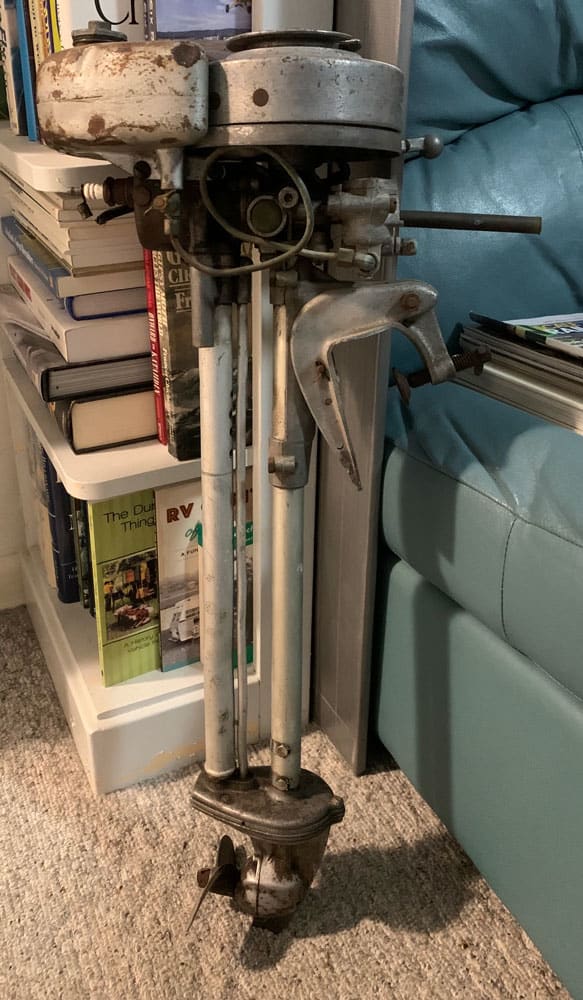

As readers of my column know, I look for cool old stuff while touring the countryside in my travel trailer. While camping near the Suwannee River in Mayo, Florida, my wife and I spent an afternoon scavenging the aisles of an antiques mall in Lake City (a nearby town literally in the middle of nowhere). That’s where I stumbled upon a 1937 Evinrude Elto Pal outboard motor.

With a price tag of $150, I thought the tiny .9-hp motor would be an awesome addition to my collection of industrial art, especially if placed beneath the rusting tail of a 1930s-era airplane that was hanging in my den. My wife, on the other hand, told me to walk away from the piece of junk (as she called it), so I did.

That night, while researching the Evinrude Elto Pal’s history, I learned that when it was manufactured it was the world’s lightest outboard motor, weighing just 14 pounds. When purchased new, the Elto Pal came in a wooden carrying case (like a small suitcase) that contained the motor, tools, and accessories.

A similar Elto in mint condition, in its original carrying case, with all the tools and accessories, was listed on eBay for slightly under $12,000. What? My wife and I drove back to Lake City the following day and purchased the motor for $130 ($20 less than the tagged price). With dents and rust on the gas tank, a broken spark plug wire, nearly a century of patina on the aluminum tubing, and no carrying case, tools, or accessories, this Elto Pal was far from mint, but it still had compression.

A 1937 Evinrude Elto Pal outboard motor, with years of natural patina, finds a new home thanks to an adventuring spirit and a little eBay research.

Courtesy of Rick Cook

Being a member of the Antique Advertising Association of America (AAAA), I searched eBay for advertising related to this motor. I eventually purchased and framed an Evinrude Elto Pal advertisement that appeared in a copy of the April 1937 issue of Sports Afield magazine. Would you believe the motor sold for only $34.50 new?

An interesting discovery was made while researching the relationship between Evinrude and Elto. Ole Evinrude started the Evinrude Motor Company in 1907 but sold it in 1913. Attached to the contract was a five-year non-compete clause, which prevented Ole from selling outboard motors.

While waiting out the clause, he developed a new lightweight outboard motor using aluminum. At the end of his five-year waiting period, Ole founded the Elto Motor Company to sell his new motors. Why Elto? The contract from the sale of his first company banned him from using his own name in a competing business. Elto stood for Evinrude light twin outboard.

An Evinrude Elto Pal advertisement that appeared in a copy of the April 1937 issue of “Sports Afield” magazine.

Courtesy of Rick Cook

When the original Evinrude Motor Company got into financial difficulty in 1929, Briggs & Stratton Corporation acquired Evinrude and convinced Ole that a merger was best for everyone. Ole was named president of the merged companies, which gave him back his namesake. Evinrude was marketed as the high-end brand, while Elto was marketed as the low-end brand. Though Elto outboards were last produced in 1941, Evinrude continued manufacturing motors until suddenly going out of business in May 2020.

During my travel trailer road trips, I’ve come across evidence that I’m not the only person who collects antique outboard motors. While recently camping in St. Augustine, Florida, I saw a mailbox that was mounted inside an old Evinrude outboard motor. Not being shy, I walked up to the front door, rang the bell, and asked the homeowner if he’d mind if I wrote an article about his unique mailbox. Mind? He was flattered.

Being boaters and living in a house next to a canal with access to the Intracoastal Waterway and the Atlantic Ocean, Bob and Jan Beach (no pun intended … that’s truly their last name) wanted a mailbox with a nautical theme. Jan wanted a huge manatee-shaped concrete mailbox. Bob overruled and instead converted a 1962 Evinrude outboard motor into a one-of-a-kind piece of functional industrial art by removing the inner workings of the powerhead and fitting a metal mailbox inside. The Evinrude mailbox is mounted near the street in front of the Beach’s house. Bob purchased the 10-hp motor for $20 at a garage sale, originally intending to use it for parts.

A nautical-themed mailbox made from a 1962 Evinrude outboard motor handles the mail nicely for Bob and Jan Beach in St. Augustine, Florida.

Courtesy of Rick Cook

After telling Bob about my .9-hp Elto Pal and talking about boats, he asked if I’d like to see his antique wooden runabout. I couldn’t say yes fast enough. In his driveway, sitting on a trailer beneath a canvas shade awning, was a 1957 Lyman fitted with a 1962 Evinrude Starflite IV outboard motor. His father had purchased the 18-foot Lyman new. Bob inherited it 25 years ago. The boat’s white exterior looked freshly painted, the interior’s varnish work was pristine, and the 75-hp outboard looked seaworthy. It just goes to prove my motto – never be shy about seeking out cool old finds.

I was fortunate to have caught Bob at home when I knocked on his door, because he was just days away from towing the Lyman up to Clayton, New York, where he and Jan spend the summer months living aboard their 40-foot trawler (christened “Summer Island”). They use the Lyman for daytrips on the St. Lawrence River, but sometimes take it as far as Sackets Harbor on the eastern shore of Lake Ontario.

This beautiful 1957 Lyman runabout fitted with a 1962 Evinrude Starflite IV outboard motor belongs to Jan and Bob Beach, who inherited it twenty-five years ago.

Courtesy of Rick Cook

As a fun historical aside, I’d like to refer back to the opening paragraph of this article, in which I mentioned camping in the town of Mayo, Florida. This tiny town (population 1,055 in the 2020 census) was named after James Mayo, a colonel in the Confederate Army during the Civil War, who happened to be doing survey work in the area during the town’s founding in the late 1800s.

On August 25, 2018, the town was temporarily renamed Miracle Whip, Florida. This was done as a publicity stunt by Kraft Foods, owner of the sandwich spread brand. The name Mayo was painted over on the city’s water tower and replaced by the words Miracle Whip. In an even bolder move, the words Miracle Whip Fire Dept. were painted on the town’s fire station. Kraft Foods paid the town $15,000 for the stunt and held a picnic for residents on that Saturday. As souvenirs, Kraft Foods gave away T-shirts stating, “Proud to Be from Miracle Whip, Florida.” Miracle Whip was first sold during the 1930s as a less expensive alternative to mayonnaise and has been competing for its market share in grocery stores ever since.

Another fun historical aside relates to camping near the Suwannee River, which I also mentioned earlier. The Suwannee River was made famous by the song “Old Folks at Home,” written by American composer Stephen Foster in 1851 and more popularly known by the song’s lyrics “Way Down Upon the Suwannee River.” I learned about the history of this song while visiting the Stephen Foster Folk Culture Center in White Springs, Florida (40 miles northeast of Mayo) during that travel trailer road trip.

Foster was born just outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1826 and sold his first song when he was just sixteen years old. He wrote “Old Folks at Home” as a ballad about slaves living on a southern plantation.

The 1939 film “Swanee River,” starring Don Ameche, Andrea Leeds and Al Jolson, tells the story of troubadour Stephen Foster.

Courtesy of Heritage Auctions

When Foster’s brother, Morrison, read the original lyrics, he made a comment that the Pee Dee River (which ran from the Appalachian Mountains in North Carolina to the Atlantic Ocean in South Carolina) didn’t sound lyrical enough, so the brothers searched through an atlas until they stumbled upon the name Suwannee River, which sounded more fluid in the lyrics than Pee Dee River. Using artistic license, Foster changed the spelling to Swanee because the lyrics only had room for two syllables. With that, a hit song was crafted.

Although Foster was one of America’s greatest songwriters, having written over 200 tunes (including “Camptown Races,” “Oh! Susanna,” and “My Old Kentucky Home)”, he was a lousy businessman. Foster sold the rights to “Old Folks at Home” for a mere $100 and never received another penny of royalties from that tune. When he died from alcoholism in 1864 at the age of 37, he was broke.

An interesting sidenote: Stephen Foster never visited Florida and never saw the Suwannee River, the body of water he made famous in song (which became Florida’s official state song in 1935).

A portion of this story first appeared in PastTimes, the official newsletter of the Antique Advertising Association of America, and is used with permission. For more information on the group, visit www.pastimes.org.

You Might Also Like

A ‘Fuel-ish’ Space-Age Attraction