If you’ve been watching Netflix’s audacious period drama, Bridgerton, and have been able to focus on more than all of the scandalous ribaldry going on, you may have noticed the nod to the bygone ballroom accessory: dance cards.

Set in 1813 London, the Regency-era romance — watched by 82 million households around the world — is Netflix’s biggest hit ever and was just renewed for a third season. Based on romance novels by Julia Quinn, the show centers on eight close-knit siblings of the powerful Bridgerton family as they are presented at court and attempt to find love.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a Regency romance must be in want of glittering ballrooms, witty banter, a piquant heroine and a dashing leading man. Bridgerton has all that and a lot more. The show centers on the relationship between roguish Simon Basset (Regé-Jean Page) and debutante Daphne Bridgerton (Phoebe Dynevor).

Courtesy of Netflix

In between the provocative scenes, the forgotten footnote of historical dating etiquette has made numerous appearances in the hands of Bridgerton’s leading ladies attending opulent high-society dances.

A dance card or programme du bal first appeared in Vienna before reaching the rest of Europe and the U.S. The cards were used in the 18th and 19th centuries that served to remind a lady of a particular night’s formal ball, an occasion that offered a respectable venue where men and women of society, who were interested in finding a suitable marriage partner, could mingle in an appropriate fashion. Dance cards listed the specific dances to be performed and provided lines for ladies to fill in the names of the gentlemen with whom she intended to dance each successive dance with.

Dance cards and programs were typically designed to be valuable keepsakes. The ones made for the elite of Austria-Hungary were particularly elaborate, with some incorporating silver and other precious metals, jewels, ivory and mother-of-pearl. They can be found today at flea markets and antiques shops, as well as online sites including Ruby Lane, Etsy and eBay for anywhere between $20 to more than $1,000 for fancier ones made of silver or mother-of-pearl.

A fan-shaped Programme du Bal engagements card for January 11, 1887, published by M W & Co Ltd. After the event, the card was kept as a souvenir of the evening, perhaps finding a place in the lady’s drawing-room album.

Courtesy of The Ephemeral Society, UK

Inside the card is a list of all the dances for the evening including valse, polka, lancers and quadrille, and the names of partners for those dances.

Courtesy of The Ephemeral Society, UK

They were typically sized to fit comfortably in a woman’s palm and would have a cover indicating the sponsoring organization of the ball and a decorative cord that could be attached to a wrist or ball gown. Sometimes the cord was used to attach a pencil, but it was reasonable for a gentleman to carry his own and “sign up” or “pencil in” his name to declare his engagement for a specific dance with an available woman. While dance cards were generally a lady’s accessory, the gentlemen were expected to remember who they’d requested to dance, and who they might call on again in the hope of continuing a courtship.

The earliest dance cards were likely in the form of a hand fan, which had already been an essential accessory of a fashionable woman’s arm for centuries and used as a subtle instrument of seduction to communicate unspoken sentiments across the room. If a woman rested her fan on her right cheek at a ball, for instance, it meant she accepted an invitation to dance and permission to collect her interest’s name.

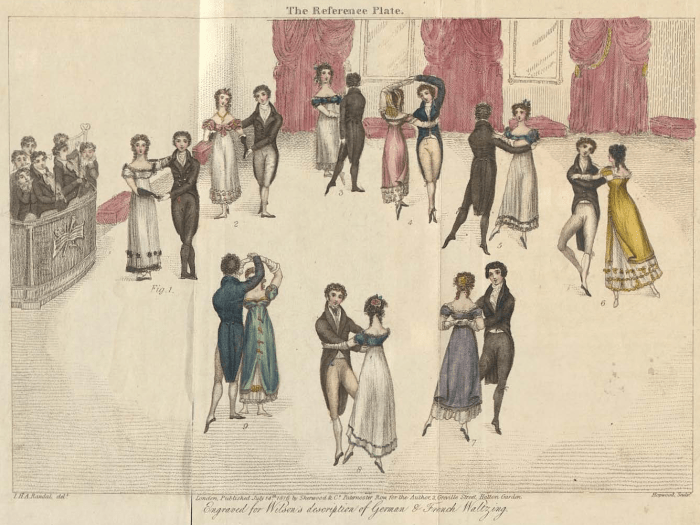

The steps of Regency waltzing including the Four March Steps, the Slow Waltz, the Sauteuse Waltz, the Jetté Waltz and German Waltzing, 1816.

Courtesy of the Library of Dance

“The Five Positions of Dancing” from Thomas Wilson’s Analysis of Country Dancing, 1811, wherein all the figures used in that polite amusement are rendered familiar by engraved lines. The colored illustrations of dancers show foot positions of a learner, while the line drawings below each dancer show the positions of a “finish’d dancer.”

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

In the high-stakes game of ballroom etiquette, the act of asking a lady to dance had to be carefully orchestrated. A gentleman was advised to stand at a comfortable distance from the woman, bow toward her slightly and request the honor of her presence as a dancing partner — never being overly sure of himself or hasty, and never asking the same lady to accompany him for more than four dances. He was also expected to always be well acquainted with a dance before participating, since any mistakes he made would put his partner in an awkward position. Having two left feet would be a social death knell. In turn, a lady was not expected to refuse a gentleman’s offer unless she had already accepted another proposal. This is where the expression “my dance card is full” came into play to give someone a polite brush off.

Dance cards remained in use well into the 1920s, even lingering into the ’30s in some cases, particularly at colleges and universities, before disappearing from the social scene. With the Jazz Age came more spontaneous dances like the Foxtrot, Swing and Charleston, and the formalities of 19th century social etiquette faded as traditional ideals were rejected by a new generation.

But one little memento of the forgotten dance card remains today. The common phrase, “to pencil someone in,” is an expression that derives directly from the lost romance of promising someone a dance at the ball.