Marjorie Merriweather Post was one of America’s wealthiest and most powerful women and one of the most famous heiresses, socialites and philanthropists. She was also quite the clothes horse, who set trends and became a fashion icon, amassing a magnificent wardrobe collected over 70 years.

Post’s lifelong passion for objects that were exceptionally beautiful and impeccably constructed extended to her taste for clothing and her love of fashion is reflected in her unique style. Post not only filled her former residence, Hillwood Estate in Washington, DC, now a museum, with her vast collection of 18th-century French furniture and decorations and one of the largest collections of Czarist Russian art outside the Soviet Union, including Fabergé eggs, she also kept her clothing and accessories there. Her fashion archive includes virtually everything she had acquired and worn since she was 16 years old, complete with notes on the objects: more than 175 luxurious, embroidered evening gowns and dresses and spectacular costumes, and hundreds of accessories including shoes, gloves, handbags, fans and parasols, hats and other items that demonstrate how she loved things that were well made. She also had many fantastic jewels and was a major client of Cartier.

Post’s Sweet 16 evening dress, 1903, of white spotted tulle, ivory silk taffeta and cream silk velvet, embellished with coral beads and clear rhinestones.

Photo by Renee Comet and courtesy of Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens

Post was born in 1887 into a Midwestern middle-class family that became one of America’s wealthiest. She was the only child of C.W. Post, founder of what would later become General Foods. At 27, she inherited the Postum Cereal empire after her father’s suicide in 1914, making her the wealthiest woman in the country at the time.

From an early age, she loved fashion and sewed clothes for her dolls. The young Post also “used fashion to highlight her beauty and attract suitors,” according to the book, Ingenue to Icon: 70 Years of Fashion from the Collection of Marjorie Merriweather Post, by Howard Vincent Kurtz and Trish Donnally. This strategy apparently served her well, as she had many admirers and four husbands.

According to Hillwood, Post came of age during some of the most transformative times for American women in the 20th century and she played many roles throughout her life, from a young Edwardian bride in 1905, to high-profile business and society figure, to independent grande dame in the ’50s and ’60s.

Post had a keen interest in clothing and a great appreciation for the richness of fabrics, expert tailoring, and elegant design. From a confection in tulle and taffeta made for her 16th birthday to the flapper silhouettes of the 1920s and sophisticated gowns of the 1950s, Post’s changing styles are consistently characterized by fine craftsmanship and beautiful materials.

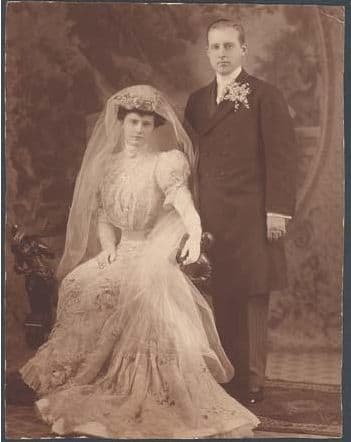

When Post wed Edward Close on Dec. 5, 1905, she wanted “the most glamorous wedding gown you could think of,” and this Hitchins & Balcom Edwardian wedding gown features lace, silver tissue, rhinestones, faux pearls, wired lilies, and cotton floss.

Courtesy of Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens

Marjorie and Edward pose for their wedding portrait.

Courtesy of Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens

Her wardrobe “reflected her personality and role in society,” said Kurtz, who also curated the 2015 exhibit, “Ingenue to Icon: 70 Years of Fashion from the Collection of Marjorie Merriweather Post.” Kurtz was hired by Hillwood in 1997 to catalogue Post’s fashions and has worked there since. He said that labels didn’t matter to her. For example, the silky, white sleeveless gown that opened the exhibit and that she wore in what is considered one of her most striking portraits, doesn’t even have a tag. “It was probably ripped out,” said Kurtz, “because she didn’t want anyone to know where she got it.”

Cut on the bias, Post accessorized that gown for her portrait with fur, rubies and diamonds, fine exponents of the Hollywood glamor of the ’30s and ’40s when she was married to Joseph Davies, who was ambassador to the Soviet Union.

Post didn’t care about labels and removed the tag from this cream silk crêpe and cream organza evening dress, circa 1933.

Photo by Renee Comet and courtesy of Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens

Post wore the dress in this portrait painted by Frank O. Salisbury (1874-1962) New York City, 1934. She accessorized it with pearls and red jewels.

Photo by Edward Owen and Courtesy of Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens

Like most women of her stature, the museum says that Post worked closely with fashion designers across Europe and the United States to create her distinctly elegant appearance over the course of her life and relied on Parisian houses, like Callot Soeurs, which she encountered while visiting the 1900 Paris Exposition. A high-waist gown in sheer turquoise moire from 1907 is a good example of her look at the beginning of the century.

Evening dress designed by Callot Soeurs, Paris, circa 1907, turquoise silk moiré, turquoise cotton moiré, orange/gold silk crêpe, orange tulle, turquoise/gold silk cotton floss, turquoise/gold silk ribbon cord and beading.

Photo by Edward Owen and courtesy of Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens

Other fashion highlights in her closet include “a Charles James knockoff,” a satin, taffeta gown purchased from Bonwit Teller; gems from Bergdorf Goodman, a favorite shopping destination since her school days when she was finding her fashion sea legs, including a frothy pink number overwrought with bows and multiple layers of silk ribbon, from 1904, and a Roaring Twenties sleek and chic black flapper-style dress; and a “Suffragette suit” worn for her visit to see President Woodrow Wilson. By the time Post reached the zenith of her power as a hostess and philanthropist, she favored the “New Look,” innovated by Christian Dior, with its cinched waists and full skirts. A pale blue ballerina-length dress from the mid-1950s highlights that era’s fascination with the feminine form.

Kurtz said Post’s fashion archive “not only represents Marjorie’s style, but the changing styles of women in America from the turn of the century until the 1970s, and, really, representing the changes in society.”

Post bought this frothy pink graduation gown of silk lawn, silk ribbon at Bergdorf Goodman in 1904.

Photo by Renee Comet and courtesy of Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens

Post was particularly an iconic tastemaker during the 1920s and a new exhibit at Hillwood that opens on June 12, “Roaring Twenties: The Life and Style of Marjorie Merriweather Post,” will explore the Jazz Age fashion, decorative art, jewelry, and design that made her one of the most influential women during this era. The show will run through January 16, 2022.

The progress, prosperity, and liberation that characterized the 1920s had a significant effect on the role of women in America, and Post was no exception, according to Hillwood. The Post Cereal Company was thriving and she, along with new husband E.F. Hutton, established herself firmly within the new society that was burgeoning. The stylish French 18th century furnishings and decorative arts that once populated her multiple residences, the glamorous attire that typified the independent “new woman,” and her astonishing collection of exotic gems and jewelry tell the story of the Roaring Twenties through the lens of one of its most influential women.

Post’s fashion-forward influence in the Roaring Twenties will be explored in a new exhibit at Hillwood opening in June.

Courtesy of Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens

One of Post’s evening dresses from the 1920s: a silk velvet and rhinestone creation by Mme. Frances, Inc., New York, circa 1925.

Photo by Renee Comet and courtesy of Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens

With her marriage to E.F. Hutton in 1920, Post’s social agenda expanded to Gatbsy-level proportions, demanding splendid gowns and ensembles for parties, operas, and other lavish events for which the era became famous. Post commissioned her attire from New York’s finest dressmakers and boutiques, frequenting Madame Frances and Thurn, in addition to Bergdorf Goodman. Dresses that will be in this exhibition include drop-waisted, flapper-style gowns, dramatic capes, and custom fancy-dress ball costumes. More information about the exhibit is here.

Post died on Sept. 12, 1973, at age 86. Throughout her life, she never lost her love of clothes and her sense of style and elegance.

For more information about Post and Hillwood, visit hillwoodmuseum.org. To explore more of Post’s fashions, as well as accessories and her collections of jewelry, furniture, art, ceramics and more, visit hillwoodmuseum.org/collection.