A common 1880-1890 whiskey bottle with no label or embossing can be identified by its trademark on the bottom of the bottle.

Photo courtesy of Michael Polak

When selling at Bottle and Collectibles shows, the most asked questions are: “What makes a bottle old?” and “What makes a bottle valuable?” But, the question that usually leads to a discussion about the importance of trademark identification is: How can I identify a bottle when it has no label or embossing?

While bottle collectors rely on certain factors to determine age and value, such as condition, color and rarity, in addition to mold types, seam lines, and pontil marks, trademarks are often overlooked. Trademarks can provide the collector with additional valuable information toward determining history, age and value of the bottle, and provide the collector a deeper knowledge of the glass companies that manufactured these bottles. I have been collecting bottles for nearly 50 years and on many occasions, trademarks have been a big factor toward unlocking the mysteries of the past.

The bottom of a common whiskey bottle shows it was manufactured in San Francisco, as shown by the SF & PGW trademark.

Photo courtesy of Michael Polak

An excellent example is a common ($20-25) 1880-1890 “Amber Whiskey” bottle . The front and back are absent of a label or embossing, but embossed on the bottom is SF & PGW. Pacific Glass Works (PGW), founded in 1862 in San Francisco was very successful but encountered financial problems years later. Carlton Newman, a former glass blower at PGW and owner of San Francisco Glass Works (SFGW), bought PGW in 1876, and renamed it San Francisco & Pacific Glass Works (SF &PGW). With that trademark, you have unlocked the mystery. Now, you know you have an 1880-1890 Whiskey bottle, manufactured by SF & PGW between 1876 and 1880, in San Francisco.

Another great example is shown above, an Aqua Blue 1860-1870 “Union-Clasped Hands-Eagle With Banner” Whiskey Flask. While there is the embossing of the Stars above Union, Two-Hands Clasped, and an Eagle and Banner, it doesn’t appear to provide any additional information. Or does it? What about the letters “LF & CO” embossed in an oval frame under the Clasped Hands, and, “Pittsburgh, PA” on the reversed side under the Eagle and Banner? Author Jay W. Hawkins, Glasshouses & Glass Manufacturers of the Pittsburg Region, 1795-1910, researched the mark as Lippincott, Fry & Co, 1864-1867 (H.C. Lippincott and Henry Clay Fry, Operators of the Crescent Flint Glass Co.).

This Civil War era bottle, circa 1864-1865, was made after Fry returned from military service with the 5th Regiment of the Pennsylvania Cavalry during the Civil War where he served since August 1862. Now you have the entire picture from just a few letters and one word.

Earlier I discussed color as being a major factor in determining value. Here’s the approximate range for this flask: Aqua Blue, $100-150; Yellow Green, $1,000-$2,000; Golden Yellow, $400-600; and Amber, $900-1,200. Another note about this historical 1860-1870 Flask is that it was found in 1973, during a major dig behind a house of the same period in Youngstown, Ohio, in the trash dump located in the back yard. Five additional bottles from the same time period were also found.

In 1998 I was fortunate enough to meet the bottle collector who dug this very cool bottle, and after some very tough negotiating, I was fortunate enough to take home the treasure.

The trademark of this Old Quaker bottle provides valuable information in determining history, age and value of the bottle.

Photo courtesy of Michael Polak

So, what is a trademark? By definition, it is a word, name, letter, number, symbol, design, phrase, or a combination of items that identify and distinguishes the product from similar products sold by competitors. Regarding bottles, the trademark usually appears on the bottom of the bottle, possibly on the label, and sometimes embossed on face or backside of the bottle. With a trademark, the protection is in the symbol that distinguished the product, not in the actual product itself.

Trademarks had their beginnings in early pottery and stone marks. The first use on glassware was during the first century by glassmaker Ennion of Sidon and two of his students, Jason and Aristeas, identifying their products by placing letters in the sides of their molds. Variations of trademarks have been found on early Chinese porcelain, pottery and glassware from ancient Greece and Rome, and from India dating back to 1300 B.C. Stonecutters marks have been found on Egyptian structures dating back to 4000 B.C. In the late 1600s, there was the introduction of a glass seal applied to the bottle on the shoulder while still hot. While the seal was hot, a die with the initials, date, or design was pressed into the seal. This method allowed the glassmaker to manufacture many bottles with one seal, then change to another, or possibly not use a seal at all.

The trademark of this Old Quaker bottle provides valuable information in determining history, age and value of the bottle.

Photo courtesy of Michael Polak

Prior to the beginning of the 19th century, the pontil mark still dominated the base of the bottle. In England through the 1840s, and the 1850s in America and France, glass houses identified their flasks by side-lettering the molds. By the 1880s, Whiskey, Beer, Pharmaceuticals and Fruit Jars were identified on the base of the bottles or jars. Following the settling of the Europeans in North America, trademark use was well established. The trademark became a solid method of determining the age of the item providing the owner of the mark is known, or can be identified by research, along with knowing the exact date associated with the mark. If the mark has been used for an extended period of time, the collector will need to reference other material to date the bottle within the trademark’s range of years. If the use of the trademark was a shortened time frame, then it becomes easier to determine the age and manufacturer of the bottle. The numbers appearing with the trademarks are not a part of the trademark. They are usually lot manufacturing codes not providing any useful information. The only exception is that the manufacturing year may be stamped next to the codes or the trademark.

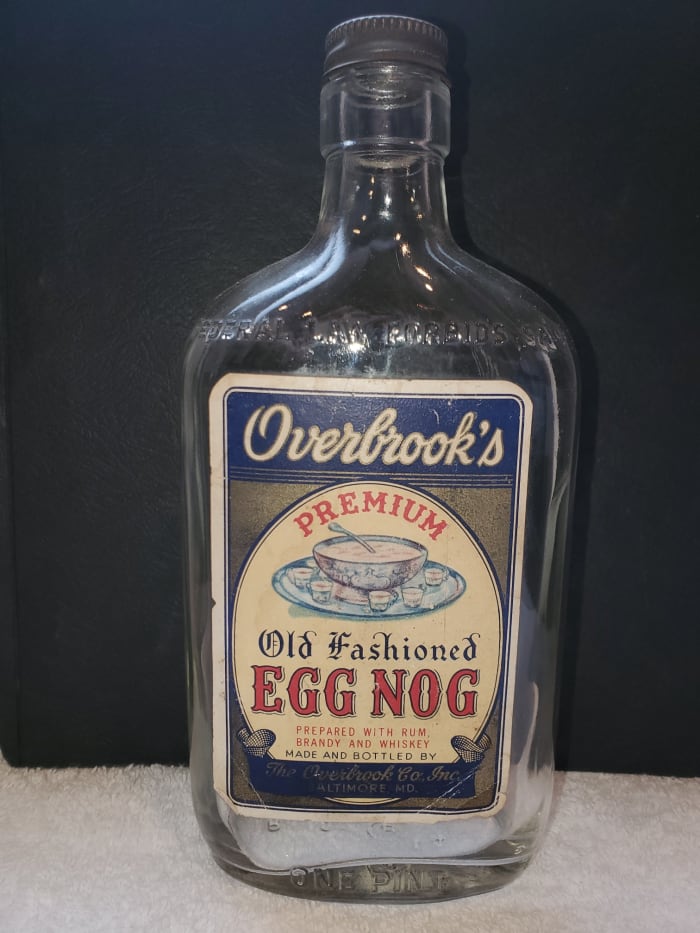

Overbrook’s Premium Old Fashioned Egg Nog (rum, brandy and whiskey), 1945. Trademark B (in circle) Brockway Glass Company, 1933-1988.

Photo courtesy of Michael Polak

While the U.S. Constitution provided for rights of ownership in copyrights on patents, trademark protection did not exist. Registration of trademarks on glassware began in 1860, and by the 1890s there were trademarks used by all glass manufacturers. Trademark registration guidelines were enacted with legislation by the U.S. Congress in 1870 resulting in the first federal trademark law. The trademark law of 1870 was modified in 1881, with additional major revisions enacted in 1905, 1920, and 1946. The first international trademark agreement, accepted by approximately 100 countries, was formalized at the Paris Convention in 1883 titled at the Protection of Industrial Property.

The next time you find that special bottle without a label or embossing, check out the base, or the lower side of the bottle. You never know what treasure you may have found.

And as always, keep having fun with the hobby of bottle collecting.

REFERENCES

Hawkins, Jay W – Glasshouses & Glass Manufacturers of the Pittsburg Region, 1795-1910, iUniverse, Inc., New York, 2009

Lindsey, Bill – SHA/BLM Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website, Email: bill@historicbottles.com. Williamson River, Oregon

Lockhart, Bill; Serr, Carol; Schulz, Peter; Lindsey, Bill – Bottles & Extra Magazine, “The Dating Game,” 2009 & 2010

McCann, Jerome J – The Guide to Collecting Fruit Jars-Fruit Jar Annual, Printer: Phyllis & Adam Koch, Chicago, IL, 2016

Rensselaer, Steven Van, Early American Bottles & Flasks, J. Edmund Edwards, Publisher, Stratford, CT, 1971

Toulouse, Julian Harrison, Bottle Makers and Their Marks, Thomas Nelson Inc New York, 1971

Whitten, David, “Glass Factory Marks on Bottles,” www.myinsulators.com/glass-factories/bottlemarks.html