“I would be very happy to see you do something stupid.”

The private investigator struggled to gain a foothold in the swinging sixties. The cast, as far as Hollywood is concerned, had all but died out in the previous decade (with a few exceptions: kiss me deadly most notable). The first half of the 1960s was all about super spies, secret agents and the fighting spirit that goes with them. The James Bond franchise, the Matt Helm franchise, etc.

When the private investigator returned, he traded post-war cynicism for post-hippie mockery. harpers (1966) got the ball rolling, and when it turned out to be a hit, the guy who turned it down, Frank Sinatra, went for it Tony Rome (1967). Aware of the tropes they were maintaining, these detectives went after them with a wink. The tongue-in-cheek era didn’t peak with Lew Harper or Mr. Rome, however. In a case of supreme irony, it culminated in the character most closely associated with the classic era: Philip Marlowe. More specifically, Marlowe in Marlowe (1969).

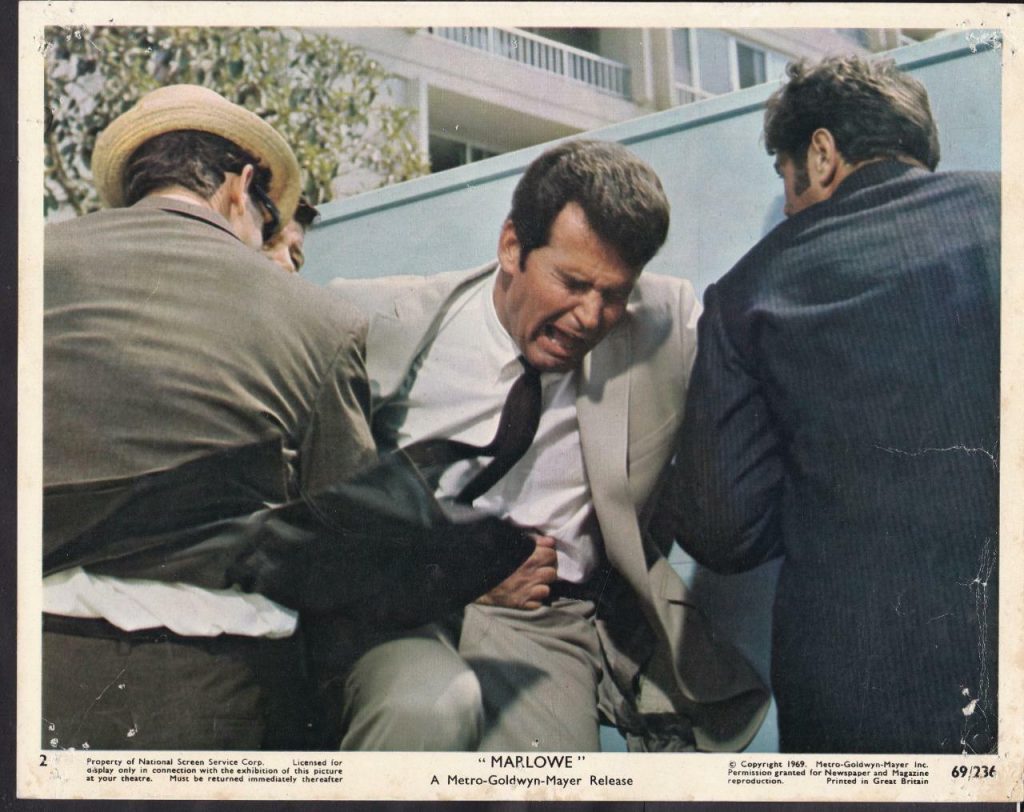

This is a stupid movie. The most famous scene shows henchman Winslow Wong (Bruce Lee) karate his way through Marlowe’s office while he just sits and watches. It reeks of gimmicks typical of the Bond films of the time and is arguably one of the least noir sequences to ever be included in an official noir. If you look at it from a particularly critical point of view, you could argue that it resembles something out of the ordinary Batman tv show. The flat lighting and Marlowe’s raid (his reasoning when the debris is discovered being “termites”) certainly welcome the comparison.

There’s an easiness about the film that hardly distinguishes it from its peers, and frankly, writer/director Paul Bogart’s adaptation leaves a lot to be desired. It’s chaotically told and the characters’ motivations are harder to follow than in the Chandler novel (which is saying a lot).

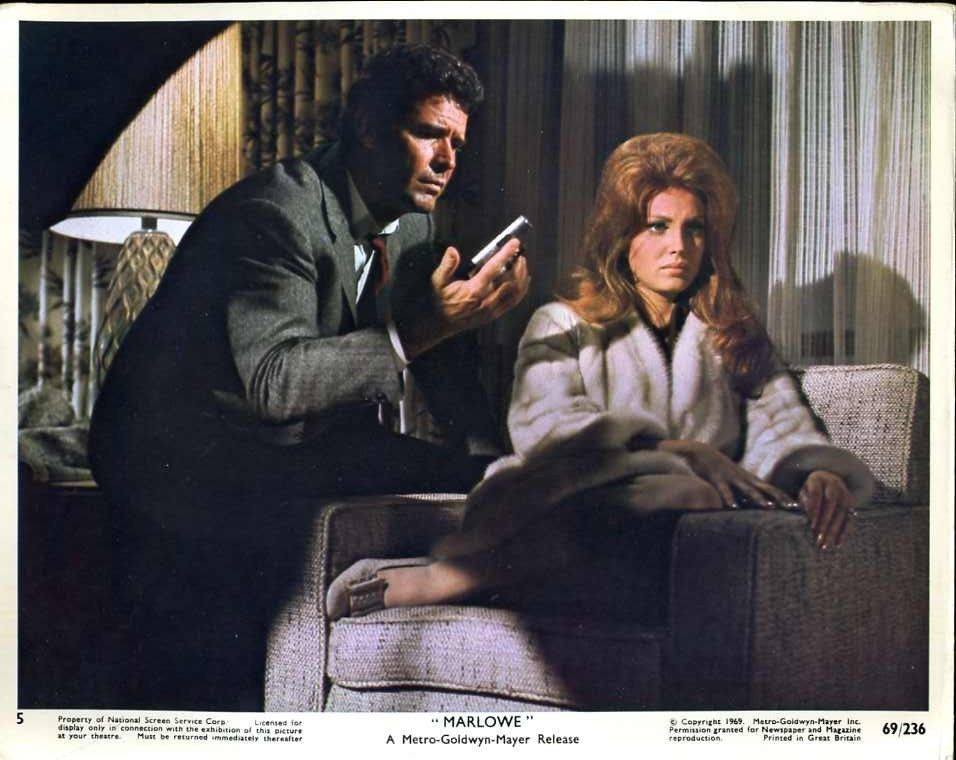

But here’s the thing: Marlowe actually quite a lot of fun. It’s not a classic, and it pales in comparison to the Raymond Chandler adaptations that preceded it (well, apart from The Brasher doubloon), but on its own it’s a charming romp with a wonderfully wry James Garner performance at its core.

Garner occupied the rare spot between the television A-list and the movie B-list. He was preternaturally likeable on both counts, but he often seemed like he was better suited to the small screen. This was undoubtedly the result of opportunity. Garner would never get a script that guys like Steve McQueen and Paul Newman didn’t pass first while he was given priority in television. He had already made a name for himself with the hit series loner, and Marlowe had a rare opportunity to show off his gift for playing tough quick talkers. If done right it could have led to more fame and sequels as was the case with harpers and Tony Rome.

Garner brings a lot to the table. His Marlowe makes a scathing comeback for everyone he meets, and he weaves together the more ridiculous elements of the plot through sheer force of charm. He also has great chemistry with the rest of the cast, which includes (not only) Carroll O’Connor, Rita Moreno and William Daniels. Moreno and Bruce Lee are particularly good here, relying less on heists and adding real emotional weight to the proceedings. The last scene of the former, which I’ll leave untouched here, is one of the best in the entire film.

That Marlowe Sequel may not have materialized in the literal sense, but in a rare instance where things worked out in Noirville, we got a spiritual sequel. Roy Huggins and Stephen J. Cannell liked Garner’s performance in the film, and Cannell was the creative man behind it loner, decided to update the formula with a modern twist. They took the central premise of Marlowe, renamed him Rockford, and hit the ground running with the classic detective series The Rockford files. Those who like the series will surely find many of its classic components in their embryonic form via Marlowe (Marlowe and Rockford share certain lines, co-stars, and even the same phone number).

Marlowe would have radical reinventions in the decades that followed, leading to Garner’s version being lost over time. It’s understandable given the cult status of the other films, but there’s still a lot to like here, if for no other reason than the fact that it’s an unknown corner of the detective’s legacy. You also spend a few hours with a Rockford files Prequel doesn’t sound bad.

TRIVIA: James Garner was taking martial arts classes at the time Marlowe was filmed. His teacher? None other than Bruce Lee.