Silents are Golden: Silent Superstars – The Early Heartthrob Sessue Hayakawa

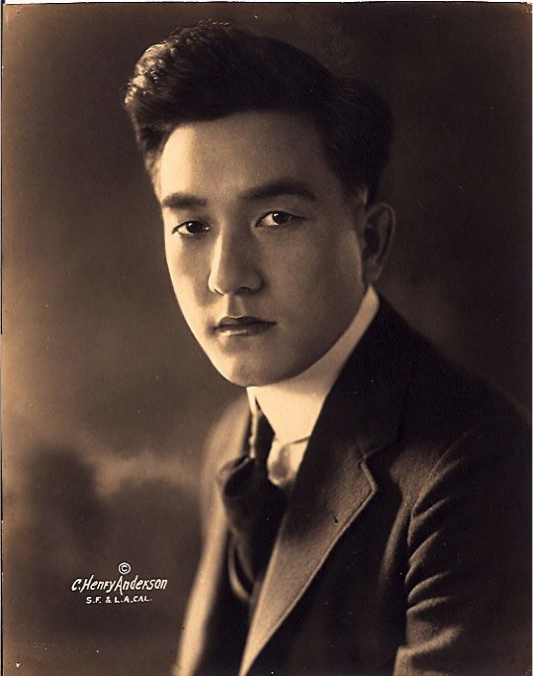

The typical handsome silent movie lead was a strong, dependable, clean guy with names like Harold Lockwood and Earle Williams. The popularity of Rudolph Valentino in the ’20s also sparked a craze for “exotic” Latino lovers. But modern film fans might be surprised to learn that there was another popular matinee idol who also seemed exciting and “exotic” to white audiences earlier than Valentino: the Japanese actor Sessue Hayakawa, a star of the 1910s.

Hayakawa’s early life was dramatic. He was born Kintaro Hayakawa on June 10, 1886 in the city of Minamiboso, Japan. He came from a wealthy family, his father was a governor and his mother had aristocratic roots. At the age of eighteen, Hayakawa attempted to join the Japanese Navel Academy at Etajima, planning to become an officer as his parents desired. When he was turned away because of hearing problems (he had torn an eardrum while diving), he attempted to ritually kill himself by stabbing himself in the abdomen. Fortunately, he was discovered and was able to recover.

He later recalled that his family then sent him to the University of Chicago to study economics, with the new goal of becoming a banker. But apparently there is no record of Hayakawa attending university, and he may have spent his time in the US doing odd jobs instead. Anyway, while spending some time in Los Angeles, he immersed himself in Japanese theater in the Little Tokyo neighborhood. Thrilled by what he saw, he decided to become an actor and adopted the name “Sessue” (meaning “snowy continent”) as his stage name.

He quickly made an impression on his fellow actors, including actress Tsuru Aoki, who later became his wife (they adopted three children). Aoki convinced film producer Thomas Ince to attend a performance of The Typhoon, and Ince decided to make a film out of it with Hayakawa. The 1914 film was a hit and was followed by The Wrath of the Gods and The victim (both 1914). Since Hayakawa was clearly a rising star, he was signed by Famous Players-Lasky (now known as Paramount).

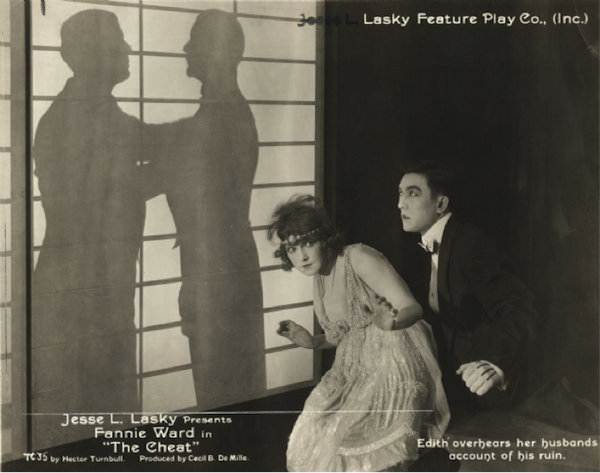

Hayakawa would prove himself in Cecil B. DeMille’s sensational drama Fraud (1915), where he played a wealthy ivory merchant. When a married high society woman comes to him for a loan, hoping to replace a large sum of Red Cross money lost on a bad investment, he agrees in exchange for sexual favors. When she tries to back down from the deal, he brands her on the shoulder – a shockingly lurid scene for the time. It was a critical and box-office hit, establishing Hayakawa as one of Hollywood’s top stars and an idol for many female moviegoers.

While his charisma and thoughtful, elegant looks certainly explain his popularity, his appeal was also fueled in part by the intense interest in Asia at the time. The exoticism of the “Far East” attracted people and had a strong influence on fashion and interior design trends. Still, concerns about miscegenation often limited Hayakawa to villain roles and prevented him from being a regular romantic lead or hero. But that didn’t hurt his popularity either, because these roles made his characters seem like forbidden fruit to countless smitten women.

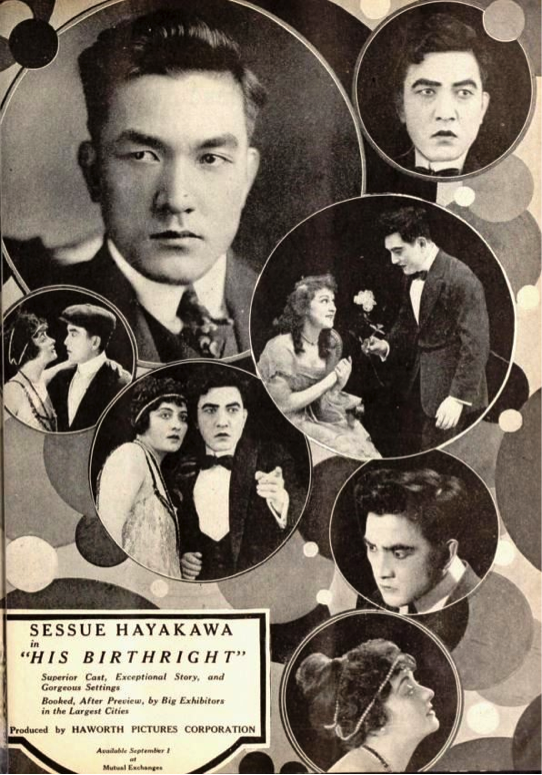

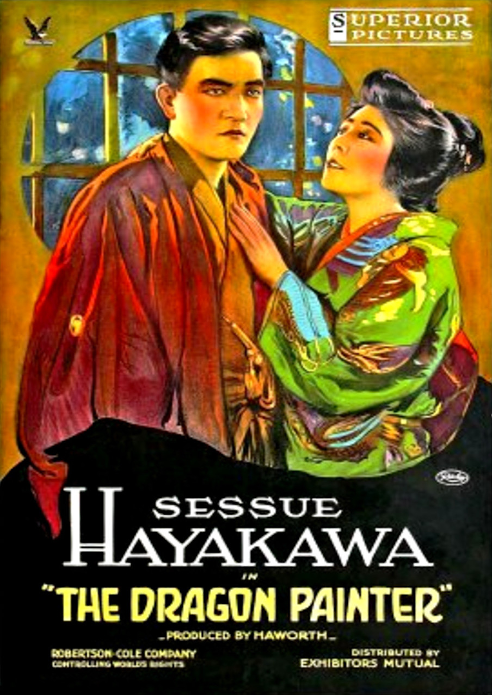

In 1918, Hayakawa grew tired of typography and decided to start his own studio, Haworth Pictures Corporation. It was the first Asian-owned studio in Hollywood, and over the next three years it would make twenty films, praised for their subtle, Zen-inspired acting. While most of them are lost today, is the most famous that survived The Dragon Painter (1919). Starring Hayakawa’s wife Tsuru, it was highly acclaimed for its authenticity and poetic story.

By the late 1910s, Hayakawa was making $3,500 a week and was happy to spend his money almost as fast as it came in. He drove a gold-plated Rolls Royce and threw big parties at his purpose-built mansion — reputedly the wildest parties in Hollywoodland. But in 1922 his career began to stagnate, helped by anti-Asian sentiment after World War I. Other problems included a ruptured appendix during filming The swamp (1921) and prosaic problems with insurance.

He decided to leave Hollywood, returned to Japan for a while, and then began shooting films in France and the UK. Not one to waste his time, he would also have a starring role on Broadway, writing a novel called the bandit prince, to adjust

The Bandit Prince into a play and to produce a stage version in Japanese The Three Musketeersand open a Zen temple in New York City.

By the early ’30s he had also found time to return to Hollywood and make his talkie debut in daughter of the dragon (1931) with Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong. Unfortunately, his heavy accent didn’t go over well and he went back to making films in Japan and France. He would even star in a remake of Fraud 1937, also called Fraud.

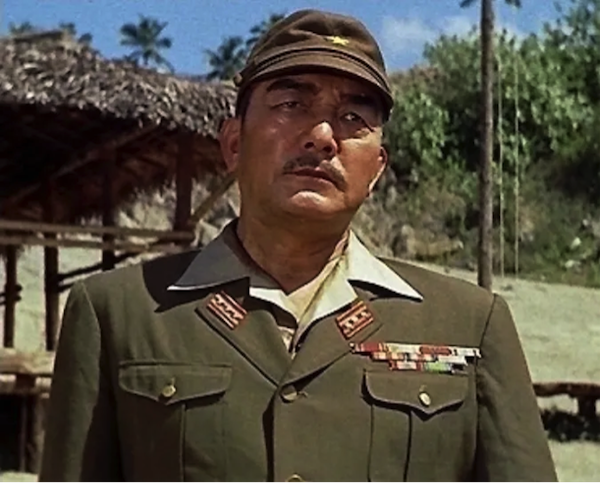

After World War II, Hayakawa was contacted by Humphrey Bogart’s production company about a role in the film Tokyo Joe (1949). This began the final leg of his acting career, in which he often played honorable villain-type roles. The highlight was his famous role as Colonel Saito in The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), which earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor and a Golden Globe nomination. Following this, he began to quit his acting career, appearing only occasionally in films and on television. In 1961 he also lost his wife Tsuru to peritonitis. His last film was stop motion The daydreamer (1966).

As a practicing Zen Buddhist, Hayakawa decided to pursue the profession of Zen priest. He also taught acting and wrote his autobiography Zen showed me the way… to peace, happiness and tranquility. He died of a cerebral blood clot in 1973, leaving behind a proud legacy of being cinema’s first international Asian film star.

…

–Lea Stans for Classic Movie Hub

You can read all Lea’s Silents are Golden articles here.

Lea Stans is a born and raised Minnesotan with a degree in English and an obsessive interest in the silent film era (which she largely credits to Buster Keaton). In addition to blogging about her passion on her website, Silent-ology, she is a columnist for the Silent Film Quarterly and has also written for The Keaton Chronicle.