By Ira Kantor

It’s been the length of my college education since I’ve last set foot in a movie theater.

But the opportunity to see the Talking Heads in IMAX? Heat up the popcorn and dispense my large Coke Zero, stat!

Already a seminal masterpiece of live showmanship, artistic ingenuity, and immersive minimalism, the Heads’ 1984 film Stop Making Sense, directed by the late Jonathan Demme, is back in theaters nationwide with the group’s quartet, David Byrne, Chris Frantz, Jerry Harrison, and Tina Weymouth making the interview rounds — and actually talking to one another. This calls for a celebration… and mandatory field trips to your local AMCs!

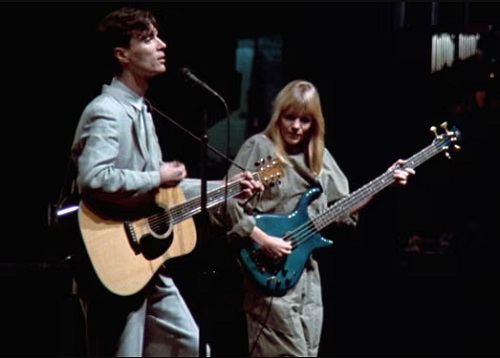

Sure, YouTube and Prime Video can put segments from this masterwork in front of my search queue whenever I click a button on the Smart TV, but there’s something wonderful about being able to recline back in a darkened room and see Byrne’s herky-jerky mannerisms fill up a giant screen. From the moment Byrne’s scuffed white sneakers come walking onto the stage at Hollywood’s Pantages Theater and he presses the boom box button to start chugging away at “Psycho Killer” — all the while looking like Bill Nye’s brother seeking to inject himself into conversation — I’m at rapt attention.

For context, Stop Making Sense captures the Heads at their most successful. Five albums in with major critical acclaim assured each time, the group has nothing to lose here. They already have their fans and their unique sound and style have been embraced by the masses. Their fourth album, Remain In Light, ranks within the 40th greatest albums of all time, as decreed by Rolling Stone.

All folks need to do is sit back and enjoy — even if their ticket isn’t for the actual show.

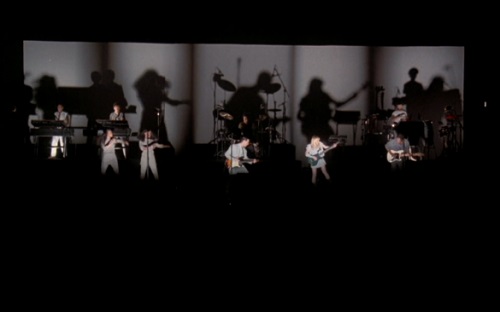

Forget “Barbieheimer.” Stop Making Sense is my vote for blockbuster of the year. For 90 minutes, I’m treated to arguably the greatest revivalist meeting slash hootenanny produced by a band. What makes this work so impactful is that Demme and the Heads don’t go for flash or uber production; they go for the groove which pours out of each member with the same ease as the sweat and spit that flies across the screen. We don’t see a group in 2D here; we’re talking — to quote the band’s lone Top 10 hit — “three-hundred-sixty-five degrees.”

The dynamism builds with each track, as the physical set follows and pieces together. From Byrne on a bare bones stage to Weymouth, Frantz, and Harrison slowly working their way in (followed ultimately by three other musicians and two backup singers), we not only see the elements of an experience come together, we can smile knowing that there WAS actually a time when the four band members enjoyed creating together, performing together, and simply being together.

There’s no emphasis on guitar solos or individual showboating. Byrne will meander on his guitar here and there (pay attention to this eventuality in “Making Flippy Floppy”) but it’s more Glenn Branca than Glenn Hughes. Instead, Byrne is the physical fulcrum creating art in real time. This includes donning that off-putting oversized suit for “Girlfriend is Better,” stumbling about to the programmed beats of “Psycho Killer,” and performing a ballet with a floor lamp during “This Must Be the Place.” Having just come off of creating the soundtrack for The Catherine Wheel, it’s nice to see Twyla Tharp’s influence still in the room and on the stage throughout the show.

The band’s rhythms, fueled with African sensibilities, are ebullient and intoxicating. You think, there’s no way this pace can sustain but then “Slippery People” shifts to “Burning Down The House” which then segways into a true highlight, “Life During Wartime.” Not only could my foot not stop bouncing but I had literal tears in my eyes as I found myself pounding my armrest in the theater, praying somebody near me wouldn’t tell me to stop.

It’s not just Byrne’s snake oil salesman look or his rapid-fire shifts from contortionist to exhibitionist that enthrall, it’s the unfettered freedom behind the music. This is exemplified by the talents of guitarist Alex Weir and P-Funk Woo-meister Bernie Worrell. Even though I’ve seen this film before, I did try looking for flaws. All I could come up with was the fact that Adrian Belew and his chainsaw guitar effects weren’t part of this film. But then I saw Weir replicates Belew’s effects on the monumental closer “Crosseyed and Painless.” So I guess that leaves — since nothing is perfect — that I wish this film contained my favorite Heads song, “The Great Curve.” Still, I’ll survive.

If Byrne is an introvert, it’s news to me. This was/is a man comfortable in his own skin and unafraid to be primal in his execution to enrapture an audience. There’s essentially no choice; apart from projected words on screens popping up periodically throughout the film, its plot and imagery revolves around nine individuals and nine individuals only. It’s this type of successful minimalism that easily sets the precedent for Byrne’s most renowned stage efforts (cough… American Utopia…cough).

And Demme and crew keep right up with him and the other band members. Nothing is missed — Weymouth’s crab shuffle during “Genius of Love” (a brief interlude featuring band faction Tom Tom Club); Frantz’s kid-like glee smashing the snare drum; Harrison weaving and swaying with backup singers Lynn Mabry and Ednah Holt as he infuses snippets of his prior band The Modern Lovers into songs whenever possible. Even when shots go out of focus, it’s all intentional to ensure we’re caught up in the kaleidoscopic wonder of what we’re witnessing.

By the time we get to “Take Me to the River,” we are all seeking salvation and catharsis. Byrne could be speaking/singing in tongues, and I’d be racing to find the closest dictionary encapsulating the language. As the song seems to go on for days and Byrne starts peeling back his clothing layers, the camera attention finally starts shifting to the audience. Before “Crosseyed and Painless’s” close, we see men, women, black, white, kids, adults — a mélange of cultures and backgrounds all uniting under the influence of a four-piece that began in Rhode Island and would attain legendary status – not just in art circles, but the narrative of popular contemporary music. Like the band, this film is relevant, and utterly universal.

“Does anybody have any questions??” Byrne asks the crowd (perhaps rhetorically, perhaps not) close to film’s end.

No… I remain too stunned to think of any…

2019 Gretsch G6120t-hr Brian Setzer Hot Rod in Candy Blue Burst #shortsfeed #shorts #gretsch

2019 Gretsch G6120t-hr Brian Setzer Hot Rod in Candy Blue Burst #shortsfeed #shorts #gretsch