Though most of us do not wear them, many can identify a sombrero, a fez, an Aussie bush hat, a Tam O’Shanter, a Glengarry, the Alpine Tyrolean hat, the Russian fur ushanka, a Greek fisherman’s hat, the conical straw Asian hat, the kippah, the kufi, bowler, top hat and beret.

Headwear is not only visually entrenched in our society; hats contribute to our verbal communication in descriptive and comparative ways. Most, if not all, of us will understand the many idioms and expressions derived from hats. Recently, I was invited to curate and lecture on a hat exhibit at a local museum, and I eagerly threw my hat in the ring. I wasn’t sure how to approach the subject, so I had to put on my thinking cap and make sure I didn’t speak through my hat, or I might have my hat handed to me. Surprisingly, the hat exhibit became one of the museum’s popular displays.

We often hear people described as mad as a hatter, wearing more than one hat, keeping something under their hat, pulling something out of a hat, pulling a hat over someone’s eyes, or someone who’s willing to eat their hat. And most of us are familiar with the expression, “If the shoe fits, wear it,” which is not the original expression. Originally, the expression, which originated in England and dates from the early 1700s, was, “If the cap fits, wear it.” The “cap” being referred to is the fool’s cap, a brightly colored cap with drooping peaks from which bells hung (you’ll see it on a joker in a deck of cards). In the United States, inexplicably, the cap became a shoe – perhaps a remnant of our revolutionary spirit.

Paramount Pictures/Corbis via Getty Images

Someone may have told us to hang on to our hat, that home is where we hang our hat, that something is old hat, hats off to you, to pass the hat, or that something is a feather in our cap. How many of us have ever told someone, “Here’s your hat, what’s your hurry?” Not you? Well, perhaps you don’t have in-laws (only kidding, maybe).

We may have done something at the drop of a hat, pulled something out of a hat, approached someone with our hat in hand, looked for something to hang our hat on, hoped our hockey team performed a hat trick, or lastly, been described as someone who wears a ten-dollar hat on a five-cent head. In Texas, there is a descriptive hat expression for someone who is all talk and has no substance: “All hat and no cattle.”

You may laugh at these hat clichés, but the point is that even though we no longer routinely wear them (except for the ubiquitous baseball or knit caps), hats are so ingrained in our culture that we continue to use and be familiar with these idioms and their meanings.

Hats have been around for thousands of years. Hats have been depicted on figures in murals discovered in Greece and Egypt that date back more than 5,000 years. In most countries, it was once highly unusual to encounter a person not wearing a hat. Throughout the world, hats were as much a part of everyday wear as any other article of clothing. In fact, in 1571, Queen Elizabeth I decreed that everyone should wear a hat on Sundays and holidays or pay a fine.

Getty Images

Even the Christian Church recognized the significance of hats, and for this reason, in addition to some questionable Biblical references, the social connotations of hats are one reason why men remove their hats in church. Because hats typically denoted social status, the removal of hats in the church was meant to signify that all men were equal in the sight of God. Of course, even with no hat in church, a man’s wealth was known by the pew in which he and his family sat – which kind of defeated the sense of equality.

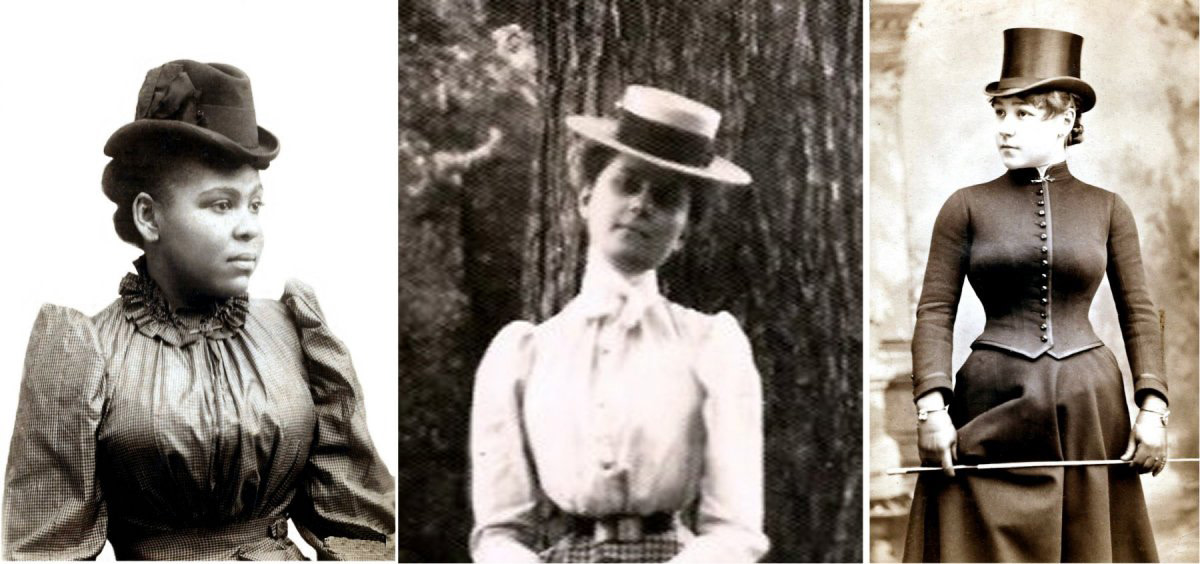

During the late 19th to the early 20th century, the wealthy upper classes distinguished themselves from the general public and even each other by dressing extravagantly and expensively. It was a time of conspicuous consumption where members of the wealthy class were identified by the cost of their possessions. A person couldn’t drag around their house, furnishings, carpets, and silver, but their clothing went with them everywhere. The amount of lace and beading on a dress or the number of gems on a neck, wrist, or finger let the world know that you had money and indicated you were from the upper social classes and, as such, better in every way than the average person. It was the same with hats. Large hats with a profusion of feathers and an extravagant and costly hat pin were all indications of wealth. The type of person my gran would say was “Dressed like Mrs. Astor’s pet horse.”

There have been times when hairstyles influenced hat styles (the calash) and times when hat styles influenced hairstyles (the cloche). During the late 18th century, most women wore simple shawls as head coverings or hats made of straw, plain cotton, or wool. Upper-class women wore elaborate bonnets of silk and satin, often over a base of straw or a framework of cane or whalebone. During the late 18th century, women’s exaggeratedly high hairstyles required large hoop-structured bonnets known as a clash.

Calash bonnets were designed specifically to accommodate the large, elaborate hairstyles that were fashionable during the late 18th to early 19th century. No matter how high a woman wore her hair (twelve inches high or higher was not unusual), decency demanded she wear a head covering. The calash also protected hairstyles from wind and rain; some were even waterproof. The name calash is derived from the French word “calèche,” which was a type of retractable hood on a French horse-drawn carriage. When indoors, the calash could be worn folded back. Outdoors, it could be drawn forward with the use of a drawstring or ribbon. Wearing a calash indicated that a woman came from the upper classes.

BONNETS: THE DOMINANT HEADWEAR

During the 19th century, the bonnet was the dominant head covering for women, and there were many types: off-the-face bonnets, poke bonnets, and draw bonnets being the most popular. A bonnet covers the crown of the head and features a small or large brim that entirely frames the face, severely restricting peripheral vision. It ties under the chin. Many 19th-century bonnets featured a ruffle of fabric at the back meant to cover the neck. This ruffle is called a bavolet, which is the French word for flap. Bonnets were often lined and decorated under the brim with flowers, tucks, shirring, and ribbons.

Until the 20th century, most women wore head coverings in the home, known as day or house caps. House caps could cover the hair completely (mob caps), expose the hair just above the forehead, or simply sit on the crown (pinners). These house caps could be plain or elaborate and made of linen, cotton, or muslin embellished with ribbons, ruffles, eyelets, or lace. During the 1860s, Mary Van Saun chose a house cap with extensions called lappets. After 1890, day caps were worn only by elderly women.

During the 19th century, a woman in mourning could be identified by her apparel; everything she wore was black. Bonnets of almost any black material were worn with crepe veiling. The crepe veiling had to be worn over the face whenever the mourning woman was out in public. The veiling was heavy, difficult to see through, and toxic. The black dye contained heavy metals, most notably arsenic. These dyes cause irritation, scarring, and respiratory illnesses. They were absorbed through the skin, mucous membranes, and respiratory tract. These toxins caused illness and, in some cases, even death. The term “widow’s weeds” is derived from the old English word for apparel, which in turn was derived from the Indo-European word “wedh,” which meant “to weave.”

During the 1890s, women’s hats became narrow and tall, so tall in fact that they earned the nickname “three-story hats.” By the first decade of the 20th century, women’s hats remained tall but also became wider, often wider than their shoulders. These milliner’s monuments were held in place by hat pins eight to ten inches long and often as long as 12 inches. Tall or wide, these hats came with problems of their own when passing through crowds and doorways.

PLUME BLOOM

In addition to their unnecessary height and gratuitous width, hats were further adorned with jewelry, flowers, and plumes from exotic birds or even the entire bird. With every movement of her head, a woman risked brushing, scratching, or poking anyone in her presence. Plumage on hats became so enormous and popular that herons and egrets, along with dozens of other birds, teetered on the brink of extinction. In fact, the Carolina parakeet, the only parrot native to North America, was hunted to extinction for its plumage.

The term “Plume Boom” refers to the first two decades of the 20th century when a number of migratory and native species of birds were hunted almost to extinction. Plumage was big business. From 1905 to 1920, more than 80,000 skins from the bird of paradise were sold in markets in New York, London and Paris. In 1911, prices for a single set of plumes ranged from $30 to $48, today’s equivalent of $1,100 to $1,400. In 1913, Eaton’s Catalogue, a Canadian mail-order catalog, offered a Bird of Paradise Aigrette for $12, which was a small fortune for the time, about $420 today. The aigrette was typically made of one or more white egret feathers.

As a direct result of fashion, the population decline in large, beautiful birds such as the great egret, snowy egret, blue heron, green heron, flamingos, spoonbills, grebes, ostriches, and bird of paradise was so severe that Congress had to enact laws to preserve what remained of these decimated populations.

CONGRESS AND SHORTER HAIRSTYLES RESCUE BIRD POPULATIONS

Two women, Harriet Hemenway and her cousin, Mina Hall, were horrified by the decimation of these bird populations and lectured and encouraged women’s groups to boycott products decorated with feathers. They, along with William Brewster, created the Massachusetts Audubon Society in 1897 and launched a boycott that led to the prohibition of wild bird feather trading in their state.

In 1913, the Weeks-McLean Law enacted by Congress outlawed hunting and interstate transportation of birds. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 prohibited the importation of feathers and the slaughter of migratory birds for feathers. These laws were only part of the reason many bird species were brought back from the brink of extinction.

As strange as it may seem, the decline in the public’s desire for feathers was based more on a hairstyle than the desire to save these birds. Women’s shorter hairstyles, which became popular beginning in 1913, no longer provided a suitable foundation for the large, heavily plumed hats worn by their mothers and grandmothers. The shorter hairstyles and incredible popularity of the cloche cap made plume-hunting no longer profitable.

CHANGING WITH THE TIMES

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, hats were de rigueur for women. They ranged in size from the small Glengarry and simple fascinators to hats of outrageous proportions with veiling, snoods, beads, and bejeweled clips. Most people wore hats every day until the 1950s and 1960s, after which the popularity of hats rapidly declined. There are a couple of major reasons for this decline. Prior to people owning cars and utilizing mass transit, most people walked to their destination and hats were required as protection against the sun or inclement weather. As more and more people began to travel by car and use public transportation, the hat was no longer required and, in fact, became inconvenient.

During the late 1950s and 1960s, hairstyles for men and women became more important than the latest fashion in hats. For women, hairstyles like the poodle cut, bouffant, beehive, and pixie cut were styles meant to be appreciated rather than hidden beneath a hat.

For men, it was the Quiff, flattops, pompadour, duck tail, jelly roll, mop tops, and afros. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, many women only wore hats on Sundays, and then three major trends occurred: the requirement for women to wear hats took on a negative connotation of subservience, church attendance began to decrease, and by 1983, the Catholic church no longer required women to wear hats or head coverings in church.

It is interesting to note that during President Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961, there was hardly a bare head in the crowd, and by Johnson’s second inauguration in 1965, there was barely a hat in the crowd.

Getty Images

Although it seems like the hat’s demise happened suddenly, it actually began during the late 1920s with young people challenging the tradition. Perhaps one day, future generations will once again wear hats to distinguish themselves from their parents’ and grandparents’ generations. Wouldn’t that be cool?

Getty Images

You may also like:

Find Yourself a Hat for all Seasons, all Reasons

Antique Hatpins: Stylish Self-Protection

How Jacqueline Kennedy Became the Fabulous First Lady of Fashion