Honoring Ray Harryhausen, a ‘Titan of Cinema’

Picture yourself standing in the middle of a fight with Ray

Harryhausen’s skeleton army from Jason and the Argonauts.

OK, it’s not the “real” skeletons, but it’s still pretty cool experience. This movie magic is an augmented reality that is one of the outstanding features of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art’s Ray Harryhausen: Titan of Cinema.

As dreamy as that sounds for Harryhausen fans, traveling to Scotland, especially for those outside of the United Kingdom, may still not be an option. But I wouldn’t tease you – or me – if there wasn’t a way we could see the exhibit.

Understanding the extensive Harryhausen fandom across the world, the gallery has created a virtual experience we can explore from anywhere. Yes, we’re all feeling “virtual” fatigue right now – especially since virtual events can fall short of the in-person experience – but this is very good and worth your time.

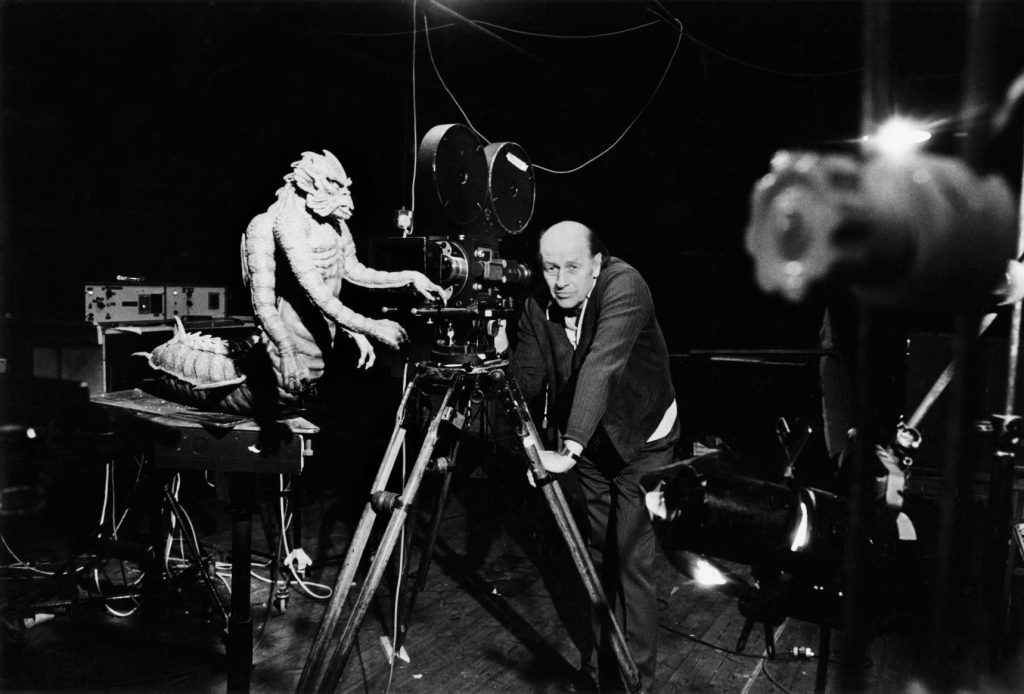

Ray Harryhausen: Titan of Cinema Virtual Exhibition Experience works well because it provides a visual experience close to what we would have in the museum – sans fighting with a skeleton. There are original sketches, storyboards, photos, memorabilia and models like Medusa, Gwangi and Pegasus. Video is of Harryhausen’s test footage, dailies and early films. Other videos allow us to hear from the man himself as well his daughter, Vanessa, who talks about watching her father work in their home.

I feel info about the exhibit is important to share because Harryhausen’s films helped make me the movie fan I am today. Without them, I wouldn’t be writing a Monsters and Matinees column. He also inspired some of the greatest talents in film such as Steven Spielberg, Peter Jackson, Tim Burton and Guillermo del Toro. And as George Lucas once famously said, “Without Ray Harryhausen, there would likely have been no Star Wars.”

Before we explore more, a bit of background first. The in-person exhibit, Ray Harryhausen: Titan of Cinema, at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (Modern Two) in Edinburgh, Scotland, is a collaboration with the Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation. It was originally planned to open in May 2020 as part of the foundation’s celebration of his centenary, which would have been June 29, 2020. Like most everything in 2020, it was delayed by the pandemic, but finally opened in October and now has an extended run to Feb. 20, 2022.

It’s called the “largest and most comprehensive exhibition ever” of Harryhausen and his work, yet it shows just a fraction of his mementos. (More on that lower in the story.)

So what is it like?

THE EXPERIENCE

Our virtual experience is broken into the same five thematic rooms as the in-person exhibit.

King Kong and the Early Years: Seeing King Kong when he was 13 put Harryhausen on his lifelong path. This segment includes very early drawings and marionettes inspired by the film, some of his Kong movie memorabilia and work by his mentor Willis O’Brien. A highlight is young Harryhausen’s diary from 1939 turned to May 21 where he wrote he had already seen Kong 31 times.

Imagination to Life:An exploration of Harryhausen’s

creative process from idea to reality including his development of model-making

techniques.

Dynamation:An explanation of Harryhausen’s famed technique of mixing animation and live action as his career transitioned from animation to feature films. This segment includes a look at eight Dynamation movies including The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955) and One Million Years B.C. (1966).

Creatures of Legend: Harryhausen moved from creature features to mythology and other stories in his later movies including the Sinbad trilogy plus Jason and the Argonauts (1963) and Clash of the Titans (1981). This segment looks at those movies. Actresses Caroline Munro and Martine Beswick are among those sharing stories.

A Life in Objects:Personal remembrances

of Harryhausen from his daughter, Vanessa.

Each section starts with a video (usually 5 to 8 minutes)

exploring how its theme relates to Harryhausen with guests like animator Barry

Purves and Oscar-winning special effects artist Randy Cook. It also has text,

images from the exhibit, sketches, storyboards and photos of Harryhausen’s

creations.

Additional one-minute videos are sprinkled throughout with clips of dailies, tests and excerpts from his early filmmaking such as Cave Bear (1935) and Evolution of the World (1938). Snippets from his colorful Mother Goose Fairy Tales are especially charming and worth repeated viewings. (He called them his “teething rings.”)

Take it at your own pace in the same way you might look through a coffee table book or photo album: You can quickly scan and flip through material or dive into the details. (Big tip: Click on any photo and another screen pops up with more information.) Your virtual ticket allows you to spend all the time you want exploring as it allows you access as often as you want through Feb. 20, 2020.

Titan of Cinema is not only entertaining, it’s educational. There’s video of the first examples of stop-motion including Princess Nicotine (1909) by J. Stuart Blackton (Vitagraph Studios) and The Camerman’s Revenge (1912) by Ladislas Starevich.

Over a few days, I kept rewinding videos, enlarging photos of sketches and storyboards to look at Harryhausen’s intense detailing, and studying the models and creatures that we’re shown from the in-person exhibit. I thought I knew about Dynamation, for example, but I went back over that segment a few times to learn more.

You’ll see glimpses of the in-person exhibit in videos and this is another spot I was constantly hitting pause to see as much as I could. Look carefully and you can see the setup where visitors “interact” with skeletons and other Harryhausen characters. (There are two clear partitions you stand between as the movie scene is played on the wall.)

In one room, a video plays on a large screen with sketches and photographs hanging nearby. On another wall, shelves are lined with character “replacement heads” used to convey emotion in stop-motion animation. Tables hold clear cases that cover some of his prized original creations. One has the “giant” bee, crab and octopus from Mysterious Island. Seeing them in the original size Harryhausen worked with is a reminder of how truly magical it was for him to bring them to giant-sized life on screen.

Sketches provide a look into his inspirations and creative process. There’s a drawing for the Pteranondon from an unrealized RKO project O’Brien worked on before Kong. Although it was never finished, it provided O’Brien skills and techniques he would use in Kong. That in turn influenced Harryhausen, as seen in a pencil and charcoal Pteranodon sequence for One Million Years B.C.

His original drawings for Beast from 20,000 Fathoms depict a quite evil looking creature with a beaklike mouth and pointy ears that could walk on two legs. He originally drew it as the marine dinosaur the Mosasaur, but changes in the script led Harryhausen to evolve it into a fictional Rhedosaurus.

There are plenty of key drawings, which Harryhausen used to realize his vision and show others how a scene would look in film once he added the creatures. In other words, these acted like storyboards. His key drawings for It Came From Beneath the Sea depict scenes of the octopus with his tentacles wrapped around the Golden Gate Bridge and the Clock Tower that look nearly identical to how they appeared in the film.

Under Mysterious Island, there’s a log crossing scene first done in King Kong and seen again in Peter Jackson’s 2005 remake of King Kong.

A major highlight are the models. Photos detail some of the models in the exhibit including the skeletons, the Cyclops (The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad), UFO’s (Earth vs. the Flying Saucers), and Kenny Key from a 1946 advertisement Harryhausen did.

A papier-mâché marionette he made of Kong as a teen is scrawny and kind of cute, but its quality isn’t the point – rather how Kong and Willis O’Brien inspired him.

One of the two complete Pegasus models from Clash of the Titans is beautiful even with a damaged wing. That happened during filming when glycerin was poured over it to make it look wet. It did the job – but also led to continued deterioration through the years.

There is so much more to see going back 90 years and

following Harryhausen’s entire career. Still it’s only a fraction of the

available material.

Where did it all come from? Harryhausen’s daughter, Vanessa, provides the answer that came from the lasting impact the Depression had on her father.

“He was a bit of a hoarder, he liked to recycle,” she says

in a video. “He didn’t throw away anything. God bless he did because we have

this incredible collection of all his stuff.”

Not only is it evident in his extensive collection that he kept everything he could, but we can see it in his work, too. He never let anything he created go to waste. If it didn’t make it in the project or film it was created for, it would be used at some point even if it took decades. The virtual exhibition shows multiple examples of this.

In the Creatures of Legend room there is a photo of an oil on canvas Harryhausen did when he was only 19. It’s a bright, colorful work of an Allosaurus fighting a cowboy with a terrified horse nearby. If that immediately conjures a scene from The Valley of Gwangi, it’s for a good reason. That original painting was created by the teen Harryhausen for a project that went unrealized; 30 years later it was inspiration for Gwangi.

We also see his vision for unrealized work, mostly through pencil and charcoal drawings, and can’t help but wonder what could have been. For War of the Worlds (1949), a film he long wanted to do, Harryhausen’s design for the alien ship has tripod legs; the alien looks like an octopus with a creepy face that has some creepy human characteristics. The Jupiterian (1937) featured a six-limbed, sinister-looking alien that only exists in the drawings and in about a minute of test footage on 16mm film.

Without Harryhausen hoarding an estimated 50,000 objects – memorabilia, sketches, storyboards, models and so much more – we wouldn’t have the chance to see this treasure trove of cinematic history. It turns out that it’s a gift to his fans, too, so take advantage of the opportunity to explore it, even if it’s from a home computer 3,000 miles away from Scotland.

HOW TO SEE IT

A ticket to the virtual exhibit is 10 pounds or about $14 in U.S. currency. Once you buy a ticket to Titan of Cinema, you have access to the virtual exhibit as often as you want to Feb. 20, 2022, the day the in-person exhibit ends. Your virtual ticket also allows you to access special live interactive experiences that will be posted on the website.

To learn more about the virtual exhibit and to buy a ticket, visit this direct link.

Be sure to look at the main website for the National Galleries of Scotland, too, since there is even more information about Harryhausen.

For more about the Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation, visit rayharryhausen.com.

* * * *

-Toni Ruberto for Classic Movie Hub

You

can read all of Toni’s Monsters and Matinees articles here.

Toni

Ruberto, born and raised in Buffalo, N.Y., is an editor and writer at The

Buffalo News. She shares her love for classic movies in her blog, Watching Forever and

is a member of the Classic Movie Blog Association.

Toni was the president of the former Buffalo chapter of TCM Backlot and now

leads the offshoot group, Buffalo Classic Movie Buffs. She is proud to have put

Buffalo and its glorious old movie palaces in the spotlight as the inaugural

winner of the TCM in Your Hometown contest. You can find Toni on Twitter at

@toniruberto.