Tobacco pipes have been around for about 500 years. The generally accepted evidence, often reprised in many treatises on the history of pipes, is an illustration of a man smoking a clay pipe that appeared in Anthony Chute, Tobacco (1595). Thus, one can conclude that clay pipe-making had to have begun around that time.

The earliest clays were simple, utilitarian, commonplace utensils, mere conveyances for holding tobacco. Eventually, three other types of pipes became what are considered, today, “high art” forms.

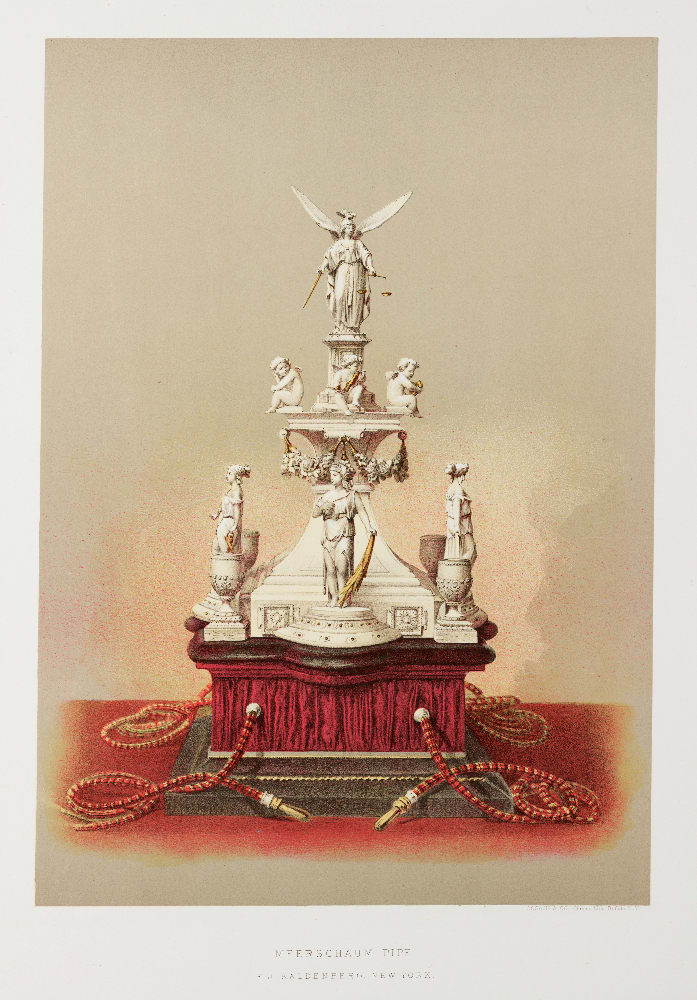

This meerschaum pipe was made by F J Kaldenberg of New York as a show piece for the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. The centennial exhibited a quantity of meerschaum pipes from all over the world and this won the only award for American-made meerschaum goods. At 28” h, it has hookah pipes, free-standing meerschaum figures representing agriculture, commerce, manufacture, and navigation, and cherubs representing music, painting, literature, and sculpture. At the top is Columbia representing power, justice and liberty.

SSPL/Getty Images

First, a look back at the early world of pipe materials, writ large. According to the 1894 Encyclopaedia Britannica, “The regular pipe-making industries divide into many branches, of which the more important are the clay pipe, meerschaum (real and artificial), and wooden bowl trades.” Not quite a complete list.

W. A. Penn, The Soverane Herbe (1902), expressed it more expansively: “Though pipes are fashioned from such varied materials as wood, stone, bronze, iron, and other metals, clay, china, asbestos, horn, and other vegetable and mineral products, pipes of clay, meerschaum, and wood form the overwhelming majority.” Penn’s list was also somewhat incomplete for not having included many other mediums, such as agate, amber, bamboo, bone, cornelian, crystal, gutta-percha, ivory, porcelain, and silver, all of which, by 1900, were in vogue as materials for smoking tobacco. They ranged from plain to highly ornate, depending on the civilization and smoking customs of a particular country.

In any serious study of the tobacco pipe as an art form, only three mediums merit this designation: meerschaum, wood, and porcelain. To be clear, starting in the mid-1700s, the woods engaged in pipe-making were not briar. This, then, is an illustrated account about pipes that are no longer produced, pipes that are no longer smoked, but pipes that are, today, prized, cherished, valued, and collected for their beauty, carving, and rarity.

This meerschaum pipe depicts the marriage of Princess Louise in 1871 to the Marquis of Lorne in Saint George’s chapel, Windsor, England, surrounded by the Royal family and court members. Attributed to Joseph Krammer, Vienna, c. 1875.

Courtesy of Piguet Auctions, Geneva, Switzerland

Meerschaum Pipes

Meerschaum (from German meaning sea foam) is a soft, white, claylike mineral found chiefly in Turkey, whose use as a pipe is believed to have begun in the mid- to late 1700s in Hungary. This mineral has been described as the aristocracy among smoking pipes; the queen of pipes; Venus of the sea; White goddess; soft and light as a fleeting dream; creamy, delicate, and sweet as the complexion of young maidenhood; one of the choicest and rarest gifts of the gods; the aristocracy among smoking pipes; and the “apple of the eye” of the refined pipe smoker.

It was a substance that was fairly easy to carve. The meerschaum occupied the tobacco throne as the queen of pipes for many years. Trained in the art of executing meerschaum pipes and cheroot holders (a smaller utensil to fit the cheroot, a tapered cigar), they worked in warren ateliers across Europe, followed later by skilled artisans in Great Britain and the United States.

Majestic meerschaum pipe carved with the figure of Poseidon, nereids and sea horses, accented with coral beads and amber mouthpiece, Austria, c. 1875; 8-1/2” h. From the Trevor Barton Collection, this sold at Christie’s in 2010 for $13,000.

Courtesy of Christie’s

A meerschaum pipe of an Arab on his steed, c. 1875-1900.

Courtesy of Piguet Auctions, Geneva, Switzerland

Pipes and holders were distinctively individual. Inspiration and ideas came from everywhere: victory and defeat in battle; the birth, marriage, and death of royalty; mythology; heroes and heroines; the hunt; and everyday life. Literature, paintings, and opera, and their authors, artists, and composers, were opportune motifs, but the carver also responded to anyone’s special request. Artistically carved and adorned with an amber mouthpiece, as was de riguer, the result was a costly article of virtu and of artistic genius.

Meerschaum pipe bowl depicting Hungarian soldiers readying for war, c. 1850.

Courtesy of Piguet Auctions, Geneva, Switzerland

Anna Ridovics, a curator specializing in antique pipe history at the National Museum of Hungary, argues that to carve meerschaum required “erudition in the applied arts,” and that these masterpieces were comparable to the larger-than-life creations in bronze, marble, alabaster, and stone of Brancusi, Cellini, Maillol, Moore, and Saint-Gaudens. Is she spot on? Check out this handful of images and decide. Today, Turkish meerschaum pipe carvers are reviving the art and craft, and I care not to make a comparison of their creations with those from a century or so earlier.

Wood Pipes

Pipes were crafted by wood turners, later by school-trained carvers in Hungary, followed by artisans in Germany and, later, in France. In the late 1700s to early 1800s, experiments were conducted on 27 different woods to identify those that exhibited the ease of carving and polishing, hardness, durability, tactility and, most important, desirability and acceptability by the pipe smoker. The survivors were alder, birch, boxwood, cherry, maple, oak, pear, and walnut. These were classified as Maserholz, the German word for any type of veined, streaked, speckled, gnarled, burled, knotted, mottled or grained bird’s eye wood.

Wood bowl of a bizarre-looking man, c. 1850.

Courtesy of the Alice de Rothschild Pipe Collection, Grasse, France

Sometimes, the bowls were carved by one artisan, and the fitted stem and mouthpiece crafted by a tradesman who specialized in making horn, ivory, and amber stems and mouthpieces. The pipes and pipe bowls that appear in this article were simply the product of the carver’s imagination or fantasy that resulted in unique, fanciful, or bizarre objets d’art.

When briar, Erica arborea, the heath tree, was discovered in the mid-19th century at Saint-Claude, France, it was found to be another suitable medium for pipes. Its popularity spread throughout Europe. Before the end of the century, the queen of pipes was dethroned; the king of pipes, the briar, took her place.

Porcelain Pipes

Hard- and soft-paste porcelain were used in the production of pipes at several European factories, some of which are still in operation: Sèvres, Chantilly, Mennecy, Saint-Omer, and Vincennes in France, and Frankenthal, Fürstenberg, Höchst, Hutschenreuther, Kopenhagen, and Nymphenburg in Germany.

As one example of the porcelain’s popularity in Germany, between 1850 and 1870, of the approximately 18.7 million pipes produced in one pipe-making center in Ruhla, 9.6 million were porcelain. (By comparison, the output from small factories in Austria-Hungary, Holland, and Sweden insignificant.)

Unlike two- and three-dimensional wood and meerschaum pipe bowls, porcelain bowls generally displayed one-dimensional art. Decorations were hand-painted portraits of important personages, landscapes, hunting scenes, commemorative events, and a host of other subject matter, often fitted with three- and four-foot stems of hardwood, ivory, or horn. Before the end of the century, as a cost-saving measure, the factory painters were fired, and decorative decals replaced the hand-painted version.

The industry prevailed for about two centuries, but the porcelain pipe swam against the tide of then-current tastes. It struggled to coexist with the more popular mediums: the simple, low-cost clay, the complex and intricately carved meerschaum, and the pleasant-smoking briar. As an aside, because porcelain is not porous and does not breathe, I contend that this invention was a pipe collector’s dream … and a smoker’s nightmare.

A closing thought or two: The number of freelance briar-pipe artisans has expanded exponentially in the last 25 years, from a handful in this country to a global community of several hundred. The briar still reigns as the king of pipes for both smokers and collectors.

Rarity of rarities: a high-relief-carved figural of a bull in solid amber, late 19th century.

Courtesy of Piguet Auctions, Geneva, Switzerland

Most of these new-age handcrafters promote their limited-edition briars on the web, and some exhibit at pipe shows around the world. Many use the term “carved” when describing their wares. I am well aware that much time and effort is invested in the delicate process of transforming a block of raw material by drilling, shaping, staining, and polishing into a finished pipe. It is a time-consuming process using power tools, machines, and elbow grease, but there is no carving in this sequence of operations! The vast majority of these briar bowls are not incised, etched, or carved in low- or high-relief. The contemporary briar pipe, less so with the modern meerschaum, continues to be a simple, utilitarian smoking device — more function than form.

Carving is “a sculptural technique that involves using tools to shape a form by cutting or scraping away from a solid material such as stone, wood, ivory or bone” … and meerschaum. Sculpture is “three-dimensional art made by one of four basic processes: carving, modelling, casting, constructing.”

Three rare pipe bowls in carved ivory from Dieppe, France, c. 1825-1875.

Courtesy of Piguet Auctions, Geneva, Switzerland

Carving and sculpture are precisely what are seen in these examples from a much earlier time in Europe when porcelain pipe-bowl molders and painters, and school-trained and apprentice-journeymen, used an assortment of simple knives, files, and scrapers to intricately and exactingly carve lifelike and imaginary subject matter. I believe that I have presented ample visual evidence of what pipe artistry once was. A renaissance of this cottage industry from a long-ago era is unlikely.

Have I whet your appetite to investigate further? Here are a few suggestions: Visit pipesrothschild.wixsite.com for more of the Alice de Rothschild pipe collection; the Tobacco Pipe Artistory on Facebook; and The Amsterdam Pipe Museum. Additionally, the web offers several articles that detail the history of these three smoking utensils of yesterday.