The normal fare offered by comic books in the 1940s was fantasy, science fiction, superheroes, hard-boiled detectives and rough-and-tumble cowboys and gunslingers, but also a lesser-known genre: real-life heroes — the mavens of medicine.

True adventure comic books spun off of the highly successful superheroes’ genre, and were presented in numerous innovative titles. Each booklet was chock-full of tales of real people, both from days long past and those contemporaneous. These comics put the fantasy world in the rear-view mirror to dwell on real people from both medical history and twentieth-century medicine, portraying them as heroes and role models who might encourage children to enter the science field as a profession. They touted the field of medicine and disseminated both medical and scientific ideas, highlighting important triumphs of medical exploration.

Though nowhere near the number of pages dedicated to Superman and Captain Marvel, this genre posted a significant readership between 1938 and 1945, the “Golden Age” for comic books about medical history.

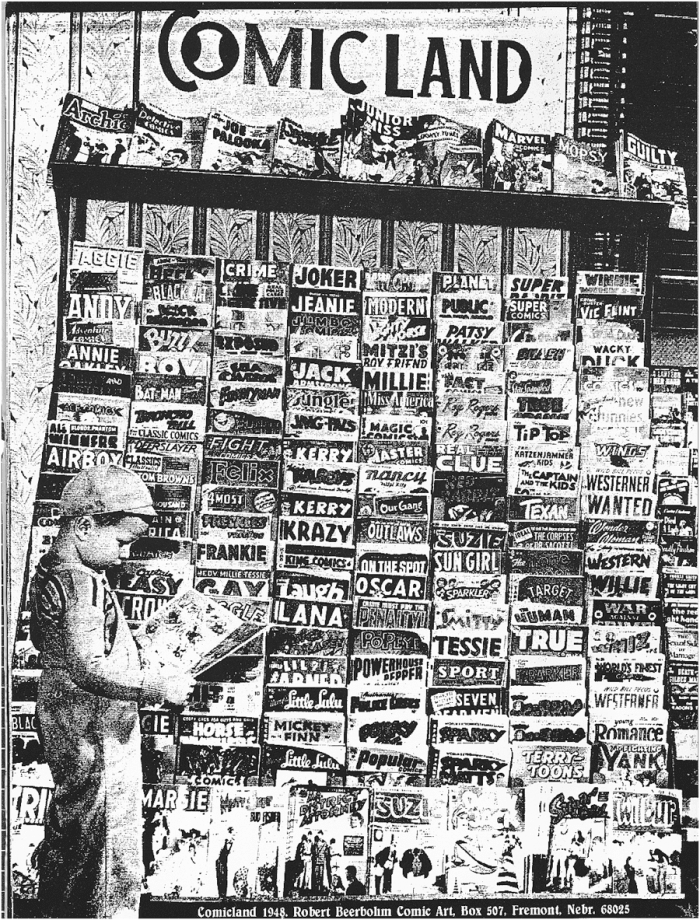

A “ComicLand” comic book stand from 1948 shows all of the choices children had for their reading pleasure, including a mix of true stories and fantasy adventures.

Courtesy of Newsdealer Magazine

Countless teens and preteens during the 1940s handed their ten cents to the person behind the counter in order to own a comic book about the adventures of French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur, modern nursing pioneer Florence Nightingale, and Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in America to receive a medical degree.

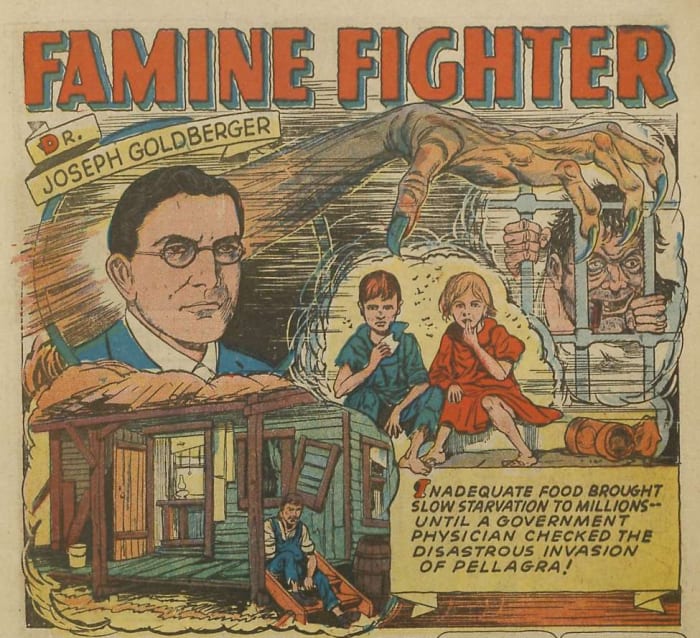

While many true adventure comic books portrayed gruesome scenes of World War II, they were considered as “wholesome adventures.” It was in that realm of true adventure comics that the medical history stories appeared in the same important vein as that of fierce war battles and other risky ventures. This new group of medical history heroes’ comic books, although educational, offered a rather novel, even visceral, approach just like fantasy action narratives with which they vied for a place on the newsstands. Real Life Comics No. 12 from 1943, for example, stars Dr. Joseph Goldberger as “Famine Fighter.” Dr. Goldberger, a physician in the U.S. government’s hygienic laboratory, discovered that the disease pellagra was caused by a dietary deficiency of niacin (vitamin B3). The comic matches Goldberger’s accomplishments with the heroism of Leathernecks on Guadalcanal.

In the pages of Real Life Comics No. 12, Dr. Joseph Goldberger, who discovered the cause of pellagra, gets the hero treatment as “Famine Fighter.”

Courtesy of Nedor Publications

Dr. Joseph Goldberger paired on the cover of Real Life Comics No. 12 with the heroism of Leathernecks on Guadalcanal.

Courtesy of Nedor Publications

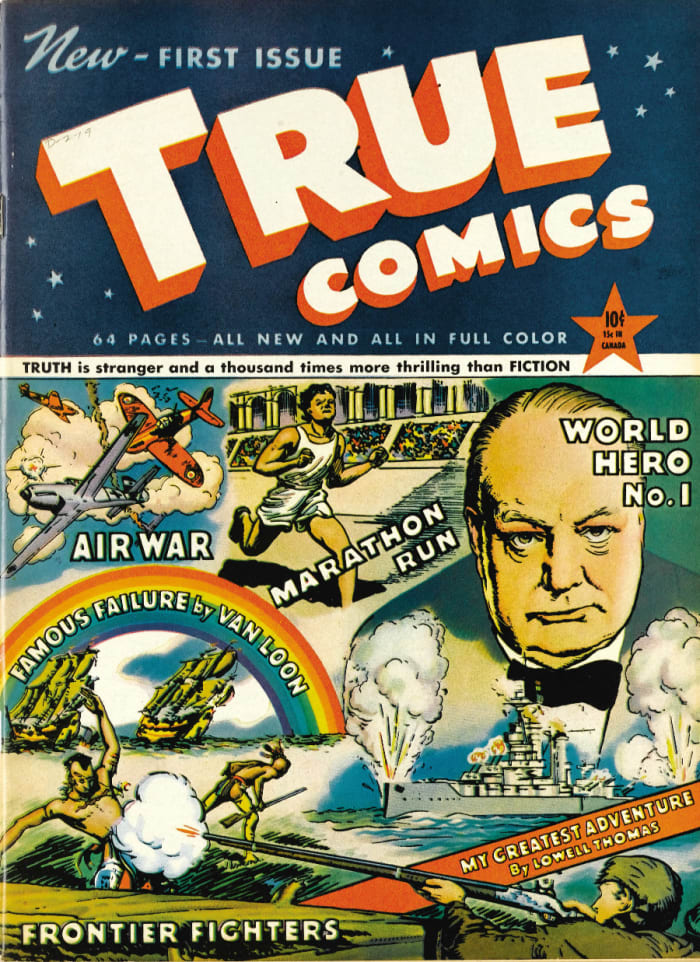

This “true” characterization first appeared in April 1941 with True Comics, with the motto, “TRUTH is stranger and a thousand times more thrilling than FICTION.” Winston Churchill appears on the cover of this first issue, and within its pages is a story about Dr. Walter Reed, a U.S. Army pathologist and bacteriologist, who led the experiments that proved that yellow fever is transmitted by the bite of a mosquito.

True Comics was originally planned to be published six times a year, but soon became a monthly issue when the premier sold out of its 300,000 copies. These wholesome adventure comics never reached high readership of comic books like Batman and Superman, which sometimes distributed over a million copies of an issue, but the expansion of the true comics genre was notable. The assessed monthly sales figures in 1944 for True Comics had increased from its 1942 numbers of around 325,000 up to a circulation high of 559,625.

The first issue of True Comics from April 1941. This sold for $1,315 at Heritage Auctions.

Courtesy of Heritage Auctions

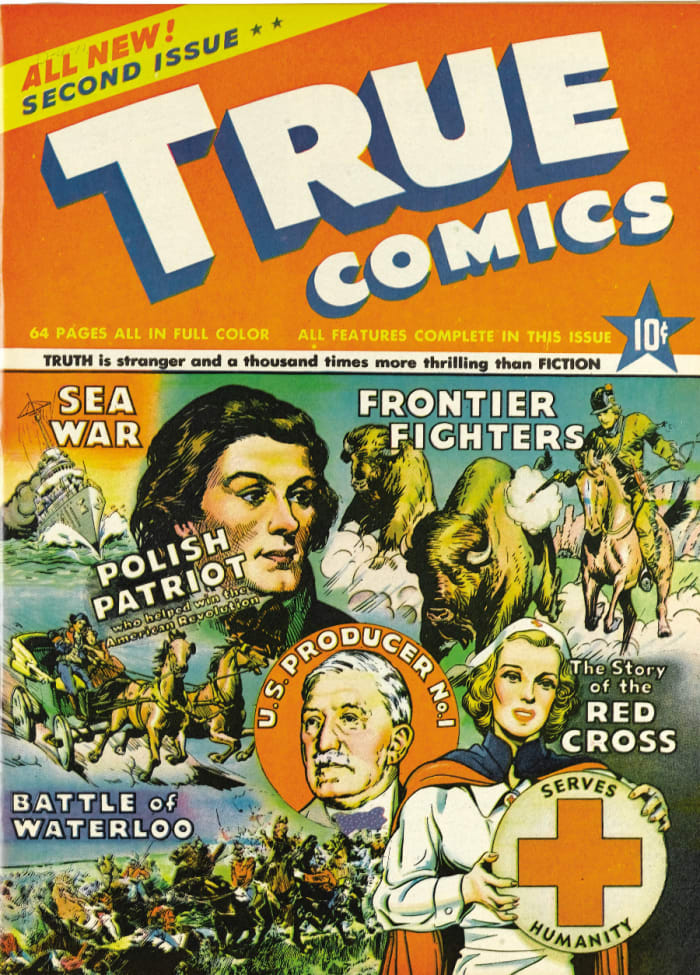

Like all comics that filled the racks at the newsstands, issues of True Comics were first and foremost a profitable enterprise, and just like all the other types of comic books, True Comics carried within its pages advertisements for bubble gum, candy, air rifles, etc. Although True Comics vied for buyers in the mass market just as other comics did, they were owned by a unique type of publisher — the Parents’ Institute, Inc., publisher of Parents’ Magazine. True Comics had a number of editors. “Luminaries” such as Mickey Rooney, Shirley Temple, and Eddie Cantor’s daughter, Janet, were included in the list of “junior advisory editors.” There was also a “senior advisory editors” board with members George H. Gallup, and two Columbia University professors, Arthur T. Jersild and David Muzzey.

True Comics No. 2 from 1941 features a story on the Red Cross and its nurses, and actress Shirley Temple was reportedly the proofreader of this issue. This sold for $508 at Heritage Auctions.

Courtesy of Heritage Auctions

Wholesome adventure comic books were not looked upon as the real deal by comic book historians, as they were not the big sellers like their cousins Batman or Superman, who reached celebrity status among millions of fans. Nonetheless, even if the true adventure comics were smaller in circulation, in artistic stature, and in the making of loyal fans and devoted historians, they created a remarkably large readership for medical history among America’s young people.

For most of the 1940s, wholesome adventure comics were enormously popular, and their pages were occupied with the likes of Pasteur and Reed, who gained the highest popularity among the medical figures in these books.

An example of the celebrity afforded the medical heroes in the late 1930s, Reed was held in the same high regard as Columbus, Sam Houston, Abraham Lincoln and Dolly Madison, as well as many other famous personages. Reed was a textbook fit for wholesome adventures, and readers viewed this stalwart American soldier as the one who defeated yellow fever. With a supporting cast of others in the medical field, the debut of “Major Walter Reed, an army doctor” in the premier issue of True Comics was true to form. This medical history was exciting and educational, chock full with observations, hypotheses, and clearly described experiments that concluded with the battle won over the dreaded yellow fever.

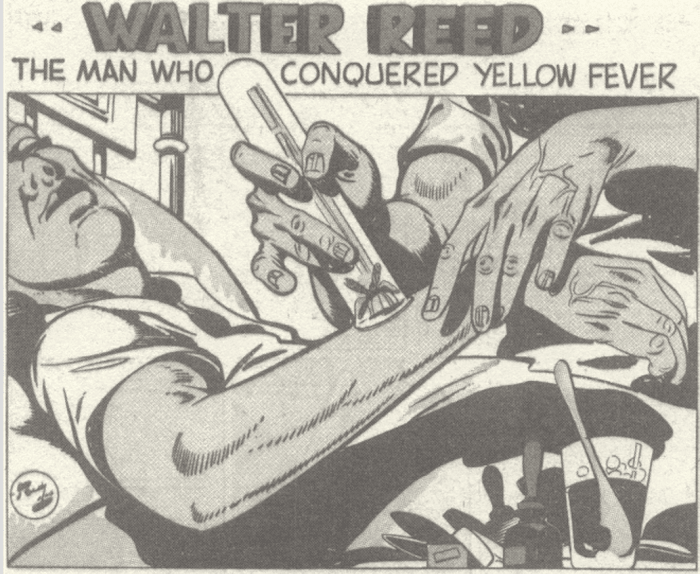

Artist Rudy Palais’ splash panel of “Walter Reed: The Man Who Conquered Yellow Fever,” in the March 1946 issue of Science Comics No. 2.

Courtesy of Ace Magazines

Real Life Comics also presented Reed and his associates’ yellow fever discovery that led to the defeat of this illness. The concluding panel of the yellow fever comic story proclaimed: “Ninety days later — for the first time in two hundred years — there was not a single case of yellow fever in Havana! Major Walter Reed and his daring associates had won another battle in the endless war against disease!”

In October 1942, Pasteur appeared in the comic book, Trail Blazers. What followed was a comic narrative in Real Heroes, titled, “Louis Pasteur and the Unseen Enemy.” This tale addresses the quandary of how good wine bottled in France arrived in England spoiled. The panes of the comic narrative highlight Pasteur’s scientific talent that solve the dilemma. Readers were drawn into action by the scenes that included the use of the microscope in isolating dissimilar clusters of microbes that were responsible for the spoiled wine. Another comic, Picture Stories from Science, also highlights Pasteur’s work.

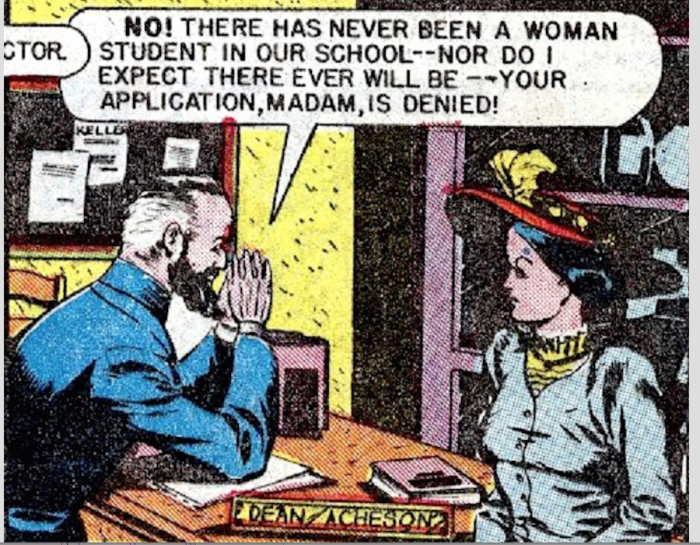

Although not American, British missionary doctor David Livingstone is certainly worth noting. An issue of It Really Happened comic book presents scenes of an African jungle adventure, showcasing dangerous animals, as Livingstone goes about his work. Added to this prestigious list was Elizabeth Blackwell, whose accomplishment as the first woman physician in America was no easy task, as her portrayal in the comic book, The Wonder Women of History, attests.

Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman physician in America, appeared in the comic book, Wonder Women of History No. 19, 1946.

Courtesy of DC Comics

As this panel shows, Blackwell’s accomplishment of becoming the first woman physician was no easy task, but she overcame the hurdles put in her way.

Courtesy of DC Comics

Even medical figures who had no research background and never solved the riddle of a certain disease also made the pages of medical history comic books, including Clara Barton. Barton’s comic book narrative not only highlights her efforts in aiding the wounded during the Civil War, but the hurdles she, as a woman, had to overcome to be allowed to access the patients. The booklet also highlights Barton’s efforts in launching the American Red Cross.

The messages put forward by these medical-themed comic books filled a niche wherein children and teenagers could learn a bit of medical history in both an exciting and educational way. The success of true adventure comics did not carry past the mid-1940s, however. With the advent of television, the passion for these comic books held by the country’s youth had waned.

But while in vogue, they offered an understanding of real heroes, not fantasy ones, who helped advance medicine through scientific discoveries.